- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Sunday, 2nd December 2012

A decidedly outraged British newspaper report on a controversial savate vs. boxing contest held in Paris on Oct. 19th, 1899. For insight into how this and other prominent savate exhibitions may have influenced Bartitsu, see “The tricks of other trades”; French boxing at the Alhambra (1898) and Speculations on Bartitsu (kick)boxing.

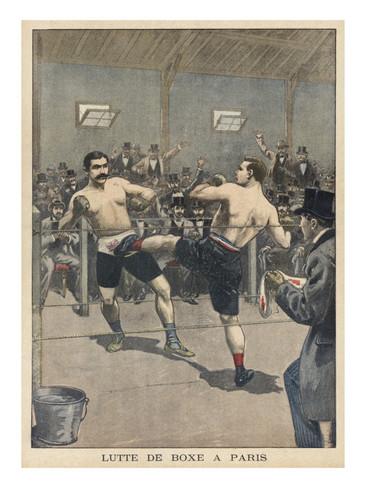

The boxing competition between Jerry Driscoll and M. Charlemont, which took place here yesterday, ended in a fiasco. Driscoll boxed in the English fashion, while Charlemont, wearing ordinary walking boots, used his hands and feet indifferently. The alleged sportsmen who organised this exhibition considered that it would decide the superiority of one style of boxing over the other, and it was surprising to hear them explain how, without the slightest doubt, Driscoll’s legs were to be broken by the first kick from his terrible adversary.

The fight took place in a riding school in the Rue Pergolese, and during six rounds Driscoll knocked his man all over the ring. In the seventh he received a foul kick in an extremely dangerous and sensitive spot, expressly forbidden by the rules, and was counted out.

Conditions of the Match

The conditions on which the encounter took place were that 4oz. gloves were to be used, the Frenchman being allowed to wear walking boots without nails. Ten two-minute rounds were to be fought, the intervals to be one minute. A competitor leaning on the ropes or lying on the ground for ten seconds was to be counted out. Another rule provided that no such blow as that which terminated the contest was to be given.

Both Charlemont and Driscoll were in good condition, but the Frenchman, though powerful, did not possess the physique of his opponent. He seemed, however, before operations began to be lighter and more graceful. One would have expected him to be quicker, but the sequel showed the contrary, and, indeed, its comparative slowness is one of the disadvantages of French boxing, which is almost useless for defensive purposes except to trained experts.

To be effective la savate exacts acrobatic qualities beyond the reach of the man in the street. That is why nobody can box in France, though kicking is taught in the Army. The result, as far as the soldiers are concerned, is that they learn to perform several spasmodic jumping-jack movements of the legs and arms of which they would never think in a fight. With the English system, on the contrary, after a few lessons a man can begin to take care of himself.

The Fight

Before the fight Driscoll was evidently at his ease, while Charlemont, who had never before found himself in these circumstances, was obviously nervous. Both were full of pluck and energy. When time was called for the first round the men circled cautiously round each other seeking for an opening. Driscoll’s tactics were to keep moving so as to avoid his adversary’s feet, and to rush in whenever an opportunity showed. Charlemont’s idea was to meet these rushes with kicks in the chest or in particular on the shins. Driscoll avoided many of these kicks with an agility that surprised the French onlookers, who were inclined to be rowdily hostile to the visitor, and even when they reached him he was nearly always able to get in a return.

One result of the fight has been completely to change the confidence of the French professors in the deadliness of the shin kick.

By the fifth round Charlemont looked a beaten man. He had received severe punishment, and his kicks had lost their force. He picked up somewhat in the sixth round, and also surprised Driscoll by changing his tactics and kicking at the pit of the stomach instead of the legs. Driscoll was staggered once or twice, but Charlemont was weakening, and at the end of the round he was seen to reel. He adopted the same tactics in the seventh round, but his foot passed between Driscoll’s legs, and the accident that terminated the fight was thus brought about. All the victim could do was to gasp out, “Oh, gentlemen, will you allow that?” and to limp, doubled up, to his chair.

The decision that Charlemont had won is inexplicable, and it is a curious comment on the organisation of the competition that the referee’s opinion was not even asked. Driscoll offered to renew the fight if he was given ten minutes to recover, and he was justly discontented at the decision being given against him on account of an accident not his fault. There were other unsatisfactory points. The intervals between the rounds were to be of one minute. In reality discussions arose on each occasion, prolonging the intervals for some minutes, which was manifestly to Charlemont’s advantage. The audience also expressed its opinions or howled advice at the competitors in a turbulent manner. In short, the whole affair was badly organised and as badly carried out. It would have astonished the frequenters of the “National Sports Club,” the professed model on which the show was based.

French Professor’s Opinion

Casteres, the well-known French professor of boxing, said of the fight to a representative of the Figaro: “I am still convinced of the superiority of the French method of boxing. But I must admit that these English beggars are better trained than we are. They have had a hundred fights in their lives, we not one. They know how to resist blows, which is one of the elementary principles of their training. We do not like blows. French boxing is intended to inflict blows, avoid those given, and not to receive any. Moreover, we are not fighters, there not being any in France. We are professors, which is entirely different.”

Reuters special service: “Ridiculously Unfair”

PARIS, Oct. 38.

Nothing could have been more ridiculously unfair than the manner in which the match between Jerry Driscoll and Charlemont was conducted. Both umpires were Frenchmen, one of them being actually Charlemont’s father, while the other was a young man who showed himself utterly ignorant of an umpire’s duty. When Driscoll, completely doubled up with pain, had been carried out there was an indescribable uproar. Amid shouts of “Vive la France “and “Fashoda,” the spectators rushed into the ring and kissed Charlemont, proclaiming him the victor. A Frenchman who was present remarked: “France needs another twenty years’ sporting education before such contests can be fought between French-men and foreigners with any chance of the foreigners receiving fair play.” The fight began at 2.50 and was over at three. Charlemont secures 25,000fr.