- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 26th September 2017

Given that we have already outlined the histories of the weaponised umbrella and hat-pin and have tested the historicity and practicality of the razor-blade cap, it seems fitting to now consider the bowler hat-as-weapon in both fact and fiction.

Perhaps surprisingly, the original bowler hat may have been designed with self-defence somewhat in mind. In 1849, London hat-makers Thomas and William Bowler received a commission to create a new type of hat for gamekeepers working on the estate of Thomas Coke, the 1st Earl of Leicester. Previously, Coke’s gamekeepers had worn top hats, which were inclined to get knocked off by low-hanging branches, and so the bowler was designed to fit snugly to the head.

Another consideration, however, was that the gamekeepers needed some protection against unexpected club-blows to the head delivered by stealthy poachers, so the hats were made from hard felt and built to take a knock.

The new style quickly became very popular among the working classes and was also adopted by members of the Plug Uglies street gang, who were rumoured to stuff their bowlers with scraps of wool cloth, felt and leather for extra protection in street fights.

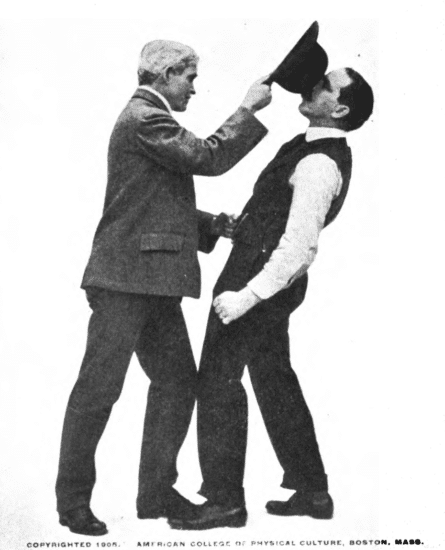

By the turn of the 20th century, the bowler had become popular among middle-class men. Simultaneously, self-defence authorities began to explore the offensive, as well as defensive, possibilities of the bowler hat, as demonstrated here in John J. O’Brien’s The Japanese Secret Science: Jiu Jitsu (1905):

Writing in La Vie au Grand Air of December 8, 1906, Jean Joseph Renaud warned his readers to beware of a “classic trick” employed by “Apache” muggers, who would courteously tip their bowlers while asking for a light for their cigars, only to convert the hat-tip into a surprise attack.

By smacking the innocent party in the face with his hat, the Apache received an instant advantage of initiative, which might then be followed up by grasping the stunned victim around both thighs and head-butting him in the stomach, spilling him backwards onto the pavement.

In L’Art de se Defendre dans la Rue, Emile Andre borrowed a trick from the Apaches, advising readers to use their own bowler hats as surprise weapons. He also recommended the bowler as an improvised hand-held shield if confronted by an attacker wielding a knife, dagger, truncheon or cane, a defensive specialty that may well have been inspired by the Spanish Manual del Baratero (1849). Andre also refers to using the hat to “beat” or strike at an opponents’ weapon, so as to disarm them.

In The Cane as a Weapon (1912), Andrew Chase Cunningham echoed Andre’s advice in recommending the hat as an improvised weapon of both offence and defence:

In case of an assailant with a knife, a very valuable guard can be made by holding the hat in the left hand by the brim. It should be firmly grasped at the side, and can be removed from the head in one motion. The hat can then be used to catch a blow from the knife, and before it can be repeated, it should be possible to deal an effective blow or jab with the cane.

In case of an attack with a pistol, a chance may occur to shy the hat into the opponent’s face and thus secure a chance to strike with the cane.

The use of the hat as a guard is, of course, not confined to the knife, but it may be used against any weapon. The only disadvantage is that it prevents passing the cane from hand to hand.

As bowler hats gradually fell out of fashion during the first half of the 20th century, so did sources treating them as weapons. By the late 1950s the idea seemed positively exotic, which may have been why it appealed to Ian Fleming in arming Oddjob, the fearsome Korean henchman featured in the James Bond novel Goldfinger (1959).

Following Oddjob’s spectacular karate demonstration, Bond asks Goldfinger why his bodyguard always wears a bowler hat:

Oddjob turned and walked stolidly back towards them. When he was half way across the floor, and without pausing or taking aim, he reached up to his hat, took it by the rim and flung it sideways with all his force. There was a loud clang. For an instant the rim of the bowler hat stuck an inch deep in the panel Goldfinger had indicated, then it fell and clattered on the floor.

Goldfinger smiled politely at Bond. ‘A light but very strong alloy, Mr Bond. I fear that will have damaged the felt covering, but Oddjob will put on another. He’s surprisingly quick with a needle and thread. As you can imagine, that blow would have smashed a man’s skull or half severed his neck. A homely and a most ingeniously concealed weapon, I’m sure you’ll agree.’

‘Yes, indeed.’ Bond smiled with equal politeness. ‘Useful chap to have around.’

As played by professional wrestler Harold Sakata in the 1964 film adaptation, Oddjob actually wore and wielded a Sandringham hat rather than a bowler, but that minor change didn’t seem to affect his aim.

The enormous popular success of the Goldfinger movie also served to reintroduce the idea of the bowler hat-as-weapon into pop-culture, perhaps most notably as used by the dapper British secret agent John Steed (Patrick MacNee) of The Avengers TV series. Steed’s primary weapon was always his reinforced umbrella, but he was occasionally seen to use his (presumably also reinforced) bowler hat to execute a surprise disarm or knock-out blow, accompanied by a hollow, metallic “bonk!” sound effect.