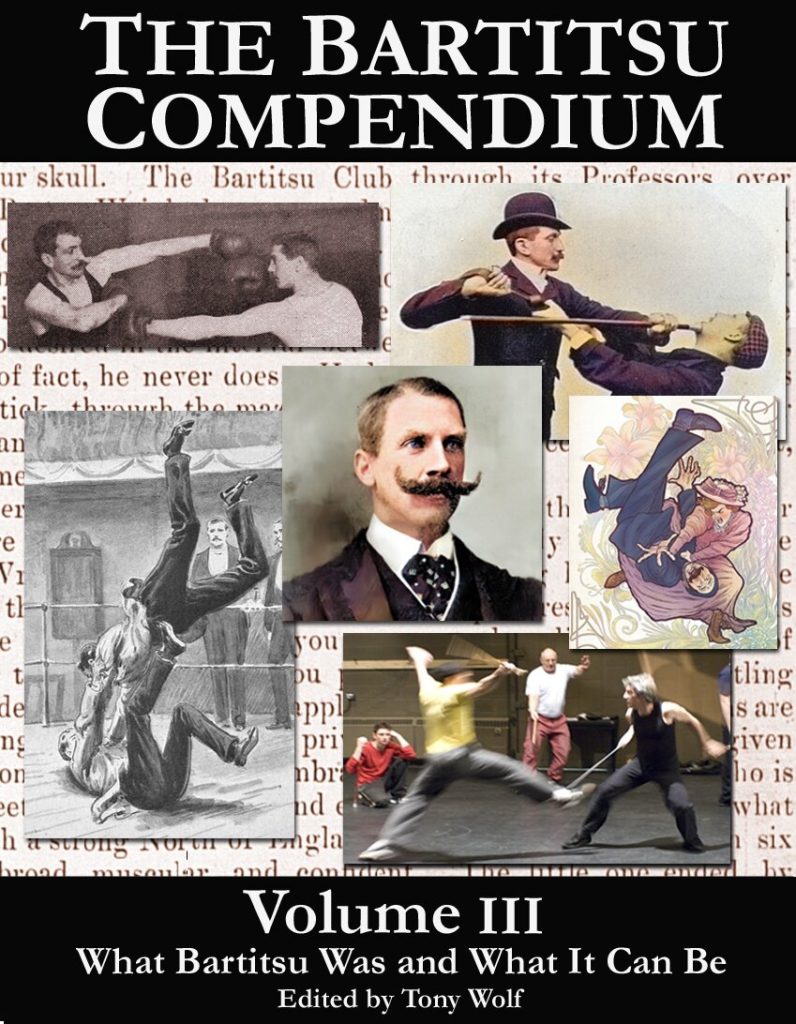

Boasting over 600 pages, the long-awaited third edition of the Bartitsu Compendium is a real treat, being an exploration of Bartitsu yesterday and today, ideal for both new students of martial arts as well as the general reader. This anthology is aimed at anyone who wants to know why attitudes to crime and violence altered throughout the nineteenth century and why some forms of physical culture went out of fashion while others gained in popularity.

It was delightful to see a rare childhood photograph of Edward Barton Wright (who would later legally change his surname to Barton-Wright), the engineer who raised public awareness of Japanese martial arts in Britain. Featured alongside his brother, he is dressed in the fashionable 1860s Zouave-style jacket and suit combination. It seems as if this tousle-haired little boy is humouring the photographer with a cheeky smile, his mind likely on interesting subjects. As my son of around the same age put it, he looks like he ‘wants to go off to build steam trains’. When it comes to the section of the book on Barton-Wright’s professional and personal life, it is clear how contributors around the world have given their support to the project, leading to some surprising discoveries about Barton-Wright.

Tony Wolf navigates the reader through the technical aspects of Bartitsu and explains, for instance, the differences between singlestick play (associated with Sherlock Holmes) and Pierre Vigny’s art of self defence with the gentleman’s walking cane. It was interesting to read that the jujutsu sacrifice throw as demonstrated during Barton-Wright’s performances was so novel because to fall upon one’s back was associated with defeat in nineteenth century English wrestling. Also, the Compendium details the various ways in which Bartitsu stick fighting was distinct from comparable systems, such as the active use of the non-weapon hand and arm.

There are articles on Enola Holmes, Honor Blackman and the jujutsuffragettes. In fact, we get a rare glimpse into Edith Garrud’s Golden Square dojo taken in 1911 and see some surprising stills from the film, Jujitsu Downs the Footpads, believed to have been lost. Alongside pieces on personal protection with the umbrella, we encounter knuckleduster jewellery, pneumatic boxing wear and Amazon self-defence against Hitler’s army – this article reminded me of Edith Garrud who reportedly told interviewer Godfrey Winn that she stood in her garden, shaking her fist at the bombers. On a lighter note, the “Velo-Boxe” cartoons always end in a chuckle, no matter how often I’ve looked at them. What added to the excitement of reading was the way that within their categories, these articles were ordered in a looser manner – one never knew what was around the next corner.