- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Wednesday, 23rd July 2014

Originally published in the Lady’s Realm magazine, Annesley Kenealy’s article offers considerable insight into the women’s jujitsu classes offered by former Bartitsu Club instructor Sadakazu Uyenishi.

IF Desdemona had been versed in “Jujitsu,” Othello might not have mourned as an untimely and penitent widower, and one of Shakespeare’s finest plays would have lacked its tragic keynote.

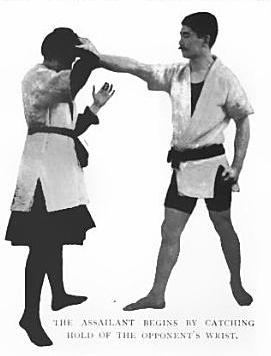

I asked Professor Uyenishi, the champion Jujitsu wrestler of the world, who has never yet been beaten, to show me just how Desdemona, howsoever frail and delicate, might have protected herself from the “neck hold” grip of the gigantic Othello.

He had not heard of Shakespeare; but he knew exactly what strangling and smothering meant, and like lightning he escaped from the deadly grip known as the “neck hold,” as shown in the illustration above — a position which, in something like ten seconds, reduces your opponent to partial unconsciousness. Hence in Japan there is a special first aid to the injured for sufferers from the “neck hold” feat. And I asked the Professor if the Japanese did not prefer to resort to this gentle, bland, and fascinating form of homicide rather than to have recourse to the brutal knife or revolver.

He smilingly assented, and said in delightful Anglo-Japanese: “It’s a lovely death — no pain like death from knives and violence. You just go off into a pleasant dream — and don’t know that perhaps you never wake again.”

The Professor has the courage of his convictions, and for my edification he allowed a gentleman pupil present to put him into the first stages of this “lovely death.” In its form it did not appear “lovely,” being far too suggestive of the real thing. But it demonstrated the fascinating subtlety of Jujitsu, which means “the defence or art of the weak.”

I went on “Ladies’ Day” to the School of Japanese Self-Defence in London, and found several feminine pupils awaiting the stroke of noon, when the Professor was to give each her lesson in the noble art of self-defence. The centre of the panelled, electric-lighted room was covered with thick, substantial matting, non-slippery and very resilient, to allow of the many falls which the jujitsu pupil must face in learning.

The Professor presented a most picturesque appearance, clad in a long, flowing, girdled gown, drawn over his fighting-clothes, which are simple and loosely fitting. Each lady chooses her own jujitsu costume, but all wear knickerbockers, a short tunic, and black stockings. Shoes are never worn, and masculine Jujitsuites invariably wrestle barefoot and bare-legged. In deference to his lady pupils, however, the Professor wore shoes. One lady had chosen black satin knickerbockers, with a short biscuit-coloured canvas tunic, without any fulness in the skirt, tied bandit fashion with a scarlet sash.

Another lady pupil adopted a very artistic blue linen blouse, with very full short skirts, blue knickerbockers, black stockings, and a white silk sash. Quite unconsciously the ladies had dressed their hair Jap fashion, though there is no denying that long tresses, however coiffed, would give a masculine — or, for the matter of that, a feminine — opponent a great advantage in several of the “locks,” speaking seriously and without any attempt to play upon the words.

The lady pupils arrive in their fighting kit, worn underneath their tailor-made coats and skirts. Some adopt Jujitsu for health — “It keeps us splendidly fit and strong” was the unanimous feminine verdict. Another uses it to reduce bulk, and attain those slender proportions which are the ideal of the modern woman.

Jujitsu does not harden the muscles. The Professor’s arms are smooth and soft as those of an unathletic woman. Neither does it coarsen or enlarge the hands and wrists. Quickness of eye and keenness of thought and perception are the leading characteristics of this “art of the weak.” It is more mental than muscular. Calculation, resource, rapid fire decisions all enter into the practice of Jujitsu; it is as though each muscle, nerve, and fibre were playing at chess.

The Jujitsuite of modest muscular power easily triumphs over brute strength used without brains. It is amusing to watch the sceptic wrestler and athlete who comes for the first time to try a bout with Professor Uyenishi, who stands 5 ft. 3 in. in his stockinged feet, and weighs but 9 st. 7 lb. The huge, large-muscled heavy-weight twirls his moustache with satisfied self-complacency. “My dear fellow,” he says, “it’s ridiculous to suppose a little chap like that has the ghost of a chance against me.”

In less than ten seconds the champion heavyweight measures his length on the matting, caught up and deftly tripped by one of the three hundred subtle, scientific, and delightfully neat movements which comprise the gentle, though deadly, art of the weak. The big wrestler picks himself up a sadder but a wiser man. He came to scoff, he remains to take lessons in this ingenious and subtle Japanese edition of self-defence.

A veritable Goliath came down to the Golden Square Academy for imparting the art to the weak, which, by the way, was the first to be established in Europe. The giant aspired to a round with the Professor, and stated that he would knock him out in thirty seconds.

Professor Uyenishi has a keen sense of humour: he laughs and smiles from morning till night, and has never been known to look unhappy or depressed. Perhaps this perennial cheerfulness is a by-product of Jujitsu. Anyway, with a twinkling eye he measured the huge proportions of the athlete who had come forth to vanquish him. After the survey, he suggested that he should first try a round with the “star” lady pupil of the school, a dainty, graceful, slightly built girl.

“I couldn‘t wrestle with a woman”, said the giant; “I should simply kill her without intending to.” However, he was prevailed upon to enter the lists with the lady.

Almost before he had time to touch her, he found himself humiliatingly at full length on the resilient matting, her knee on his chest, and held in that deadly lock which, at the victor’s will, can break wrist, elbow, and shoulder in one movement. The giant tried again, but at all points he was tripped up, at ankle or knee. From that moment he was converted to the gospel of Jujitsu.

It is whispered that “big brothers” at home, disputing the merits of the Eastern as opposed to the Western methods of boxing by brute force, have found themselves suddenly in the grip of this lithe, subtle, and fascinating form of self-defence.

As Professor Uyenishi so picturesquely puts it, “After a violent storm, it is generally the heavier and sturdier trees which have suffered most, whereas smaller plants, possessing plenty of elasticity, easily withstand the rough usage, because they offer the minimum of resistance to the opposing force. For this reason Jujitsu enables light and weak men or women to withstand heavy and strong adversaries.”

The graceful art of balance is the keynote of Jujitsu. One pupil was taking her first lesson at the time of my visit to the Academy. The Professor first taught her how to keep her balance while standing, next how to preserve it whilst walking, and finally how to keep the body in perfect harmonious balance during all the posturings assumed while practising the art. Just as in fencing you watch your opponent with a keen eye, to find him “off guard” for an infinitesimal space of time, so in Jujitsu your brain and eyes are trained to a keen perception of a moment when he is off his balance. That is your golden chance to get in the “lock” or grip most suited to the occasion.

If your adversary be too clever to allow himself to get off his balance naturally and of his own free will, your strategic aim is to force him to this artificially and against his instincts and training.

After thoroughly mastering the art of balance — an art, by the way, which confers a wonderful lithe grace and beauty of carriage on the pupils — the next step is to learn how to fall in such a way that all shock is absorbed.

You must never crook your elbows or knees, for instance, else with the sudden lightning-like overthrows so characteristic of this wonderful Japanese Jujitsu your bones would snap like a dry twig. For instance, in the position in the seventh illustration quite a small lady is shown throwing the Professor with ease, by knack rather than the exercise of muscular force, right over her head. It is the simplest thing in the world — irrespective of the weight of your adversary — once you know how, and it is very apparent to the mere spectator that the principle of “passive resistance ” underlying each position up to the most perilous and destructive “lock ” is mightier by far than any mere exercise of muscular strength. When you get your adversary into some positions, the mere pressure of one finger causes not only the most excruciating pain, but is capable of being pushed on to serious danger both to life and limb.

The underlying idea throughout is to keep the muscles and the body soft and non-resistent like India-rubber. Thus the surface of the body offers many lines of least resistance. The moment your muscles contract and harden ready for action, this fact further gives your adversary an advantage. Jujitsu is not only a graceful and delightful recreation, but it is an exact science. As in mathematics, you know exactly how your problem of position is going to work out. The science no less than the subtlety and grace of it, from the spectator’s point of view, is most alluring.

Absolute self-confidence is engendered by the art, and the more proficient among the lady pupils, in their heart of hearts, are longing for a chance encounter with a hooligan, so as to prove their prowess in the womanly art of self-defence. They picture to themselves the consternation and terror of a wayside tramp who, stopping a frail feminine little figure in a country lane to threaten and extort her purse, finds himself tossed without warning, and with a gentle hand, over a hedge.

Some of the lady pupils recently gave a demonstration at Aldershot, and so convinced were several leading military authorities that they stated at the close of the performance that “they would put their money on the ladies, were these attacked by a masculine non-Jujitsu expert of any size or weight.”

A large and successful class has been formed at Aldershot for the more militant among the officers’ wives and daughters, and regular courses are being given by Professor Uyenishi to the Army gymnastic instructors at Aldershot, who will in due course pass on their knowledge to the men under their tuition.

Prince Arthur of Connaught is taking the keenest interest in this new science of fighting. A special officers’ class has been formed at Aldershot, and military Jujitsu competitions are to be arranged from time to time.

In Japan, proficiency in Jujitsu is compulsory in the army, navy, and police forces, and everything seems to point to a similar enforcement in this country.

A six months’ pupil of Professor Uyenishi completely “floored” — in more senses than one — the chief of the Army Gymnastic Staff at Aldershot in less than one minute. This minute decided the chief to study the wrestling methods of the Far East. And Tommy Atkins is busily practising “on his own” such scraps and shreds of jujitsu as he has been able to piece together at performances given in Aldershot, at the Empire, Tivoli, and other places of entertainment in London.

Before settling down in this country, Professor Uyenishi went on a “star” tour on the Continent, receiving eighty pounds weekly, for performances in Paris, Brussels, etc. No Continental ladies applied for lessons; it remained for the stalwart athletic British girl of to-day to covet a mastery of the mysteries of Jujitsu. The Professor speaks enthusiastically of the special aptitude of the British girl for this accomplishment of the East.

“Of the English pupils,” he says, “ladies make the best. They are so enthusiastic and keen to learn. Jujitsu does not develop big, coarse muscles. It causes an all-round use of all the muscles of the body, and success depends on cleverness in balance and quickness of action. Women’s movements and minds are always quick, and these qualities make them very apt pupils. Jujitsu does not over-tax the strength of the most delicate lady, and it is the only system in the world which makes a weak woman more than a match for a strong and muscular man. For these reasons I am teaching the art to English ladies.”

One feminine pupil of six months’ standing is already so proficient that the Professor, when about to practise with her, removed his shoes – worn for etiquette’s sake — which was the greatest possible compliment he could have paid her, as he was thus approaching the more equal terms of the barefoot ideal. In chivalrous spirit, the Professor reduces his terms for lady pupils, charging three guineas only for a three months’ course of two lessons weekly, while the terms for the “stronger sex” — though all are equal by virtue of Jujitsu — twelve lessons in one month, cost three guineas, while a six months’ and a twelve months’ course of four lessons weekly cost respectively eight and twelve guineas.

Meanwhile it is apparent that the art of life and limb preserving can be acquired at a very small cost, to say nothing of the physical culture achieved incidentally.

“I have tried most forms of exercise, gymnastics, and physical culture methods, but never before found any recreation or pursuit so healthful and delightful as Jujitsu,” is the unanimous verdict of the lady pupils.

Despite the Professor’s lower fees for femininity, he says: “It’s the hardest work I do, this jujitsu for ladies. For men it is mere play to teach, but for the ladies – oh, it is such hot work,” and he mopped his moistened brow. The reason for this lies in the fact that in place of the passive non-resistant attitude he exerts towards the men, he has to actively support, and to some extent hold up the ladies, lest they might perchance hurt or abrade their skins in falling. The masculine pupils practise with one another; but the Professor‘s attitude towards the ladies’ class is so protective that he will so far allow them to practise only with him, so that he may be personally responsible for their running into no kind of danger. For similar considerate reasons he prolongs the ladies’ lessons over a space of fifteen to twenty minutes, letting them down gently and with little rests between, so as not to overtax their strength. A man’s lesson lasts little over five minutes, the science and practice of the art demanding that the utmost quickness should be extracted from the round.

The Professor is fond of telling a story to illustrate that old age is no bar to prowess in Jujitsu. The mother of a friend of his in Japan, a lady of sixty-two, was being drawn over a lonely mountain pass in a rickshaw, when she was set upon by two sturdy footpads. Although she had not practised the art for many years, her muscles had not lost the Jujitsu cunning. She rapidly and easily defeated both her assailants, and resumed her journey, in the full assurance of her capacity to defend herself against all non-Jujitsu comers.

Some such opportunity as this is longed for by all the Professor’s lady pupils, who with the zeal of the recent convert are enthusiastic to cry aloud from the house-tops the safety, security and self-confidence engendered by a mastery of the art of the weak. Jujitsu has indeed come to stay.