- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 26th January 2016

Colonel Nathaniel Newnham-Davis, who wrote a popular column for the Sporting Life newspaper under the “Dwarf of Blood” pseudonym, was clearly a connoisseur of antagonistic novelties. Of all the English journalists who covered the heyday of the Bartitsu Club between 1899 and 1902, Col. Newnham-Davis was perhaps the most enthusiastic and carefully critical.

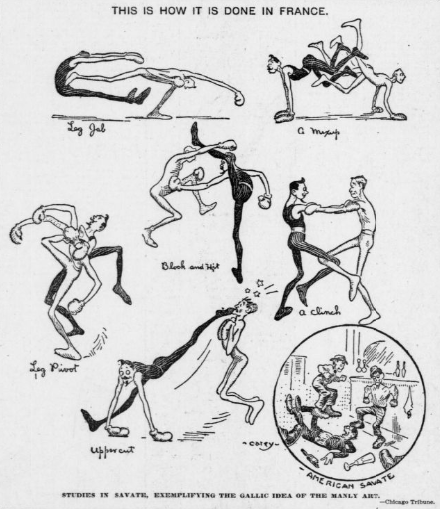

Written in October of 1898, this report on Georges d’Amoric’s savate exhibition coincides with Barton-Wright’s earliest displays of jiujitsu in London, prior to his incorporation of Pierre Vigny’s savate and walking stick combat system.

I have been studying M. Georges d’Armoric’s book on the French method of the noble art of self-defence, which begins with a pat on the back to the average Englishman. “He will not,” says M. d’Armoric, “stop at the argument of points; he will offer practical demonstrations, for who does not think himself a crack in the noble art of self-defence and the use of Nature’s weapons?”

Then M. d’Armoric, pleading for le Chausson, goes on to point out, with fine eye to a topical allusion, how good for the Hooligans a little of the noble order of the boot would be.

“Let a good number of these fellows receive their deserts at the hands” – surely it should be feet—“of their would-be victims; let a few get the treatment they delight to inflict upon the unwary and unoffending; let them feel what the weight of well and scientifically administered Coup de Chausson on the side of the face is like, or the sensation of an upper cut off the knee may be; favour your pet elect with more sport, if not yet contented, and add the lead off from the left foot, or a rounded hit off the right, accompanied by a fair concentrated arm fist blow, in the ‘mark,’ and your attacker will not ask or even wait for more.”

As a practical exposition of these kindly sentiments M. d’Armoric trotted out his professors early this week at a press performance, and they are now whacking each other with canes, butting each other in the stomach, and putting their toes in each others ears nightly at the Alhambra. That the savate is useful in street row there can be no doubt, and the question as to whether a foot was only made to stand on when there is a row forward is a question of national taste.

I recall a story of a little row in Julian’s studio in Paris. There was pugnacious young British student who yearned to make mincemeat of an equally pugnacious French student, and each was encouraged by his compatriots. Suggestions as to a duel with sabres, pistols, or mitrailleuses were put on one side, and it was decided to turn the two men loose in courtyard with only the weapons that nature had given them. The Britisher squared up in the customary style, and while he was deciding whether he would knock the Frenchman’s teeth out or put him out of his agony at once by a solar plexus blow, the Frenchman nearly cut one of his ears off with the edge of his bootsole, and then caught him a kick well below the belt, a kick that sent him running round the yard doubled with agony.

When the Britisher was able to face again the Frenchman, who had been doing pas seul in the centre of the court, he remembered some wrestling tricks he had learned in Cornwall, and closing with the Frenchman brought him to ground with a throw meant to hurt. It did hurt the Frenchman – hurt him so much that his friends came into the yard and carried him out; but the Frenchmen hold to this day that the Britisher fought unfairly, and the Britons can scarcely contain their wrath now when they discuss the Frenchman’s tactics. It was in small way a forerunner of Fashoda.

Some Frenchmen came over here and boxed at the Pelican Club the old days of its existence in Denman Street. O’Donoghue, I think, was the bhoy put up against the best of the Frenchmen, and at first the gentleman from across the channel seemed to be getting very much the best of the deal; but somebody, The Mate, I think, told the Irishman to get to close quarters and keep there, and the character of the fight changed at once. It was on this occasion that Jem Smith, asked why he would not take on one of the Frenchmen, replied that he did not want to be prosecuted for manslaughter.

But this is straying away from the Press view of the “boxeurs.” The stage, set with palace scene, was decorated with tricolour flags, and M. d’Armoric, a genial and excellently-mannered Frenchman, described to us in very tolerable English all that was going to take place. The exponents of the noble art a Francaise were two muscular-looking young Frenchmen, with small moustaches and heads closely clipped, clothed in dark blue armless jerseys and dark blue tights, with a tricoloured sash at the waist.

First they went through the outs and parries that are recommended for battle with canes. Neither shouted “A bas les Juifs!” nor Conspuez Brisson!” Vive l’Armee!” nor “Vive la Republique!” which are the cries that seem to be inseparable from cane combat in the Paris of to-day; but after the cuts and guards, and review exercise or “salute,” differing very little from single-stick exercises as know them, except that before a cut is made the cane is given a preliminary twist, the two professors a set-to with the canes, their sole protection being masks and a glove on the right hands. They were very quick with cut and parry, but occasionally one caught the other whack which sounded and must have stung.

Then they put on the gloves and went through slowly the various punches, and butts, and kicks, and the parries for them—all very interesting from a scientific athlete’s point of view, but all little wearying to the layman. This done with we came to business. The two professors sat down in two chairs, had their arms wiped by two young gentlemen, who in frock coats and faultless ties looked as different as could be to the seconds we are used to on the British platform.

M. d’Armoric called “Time,” and after the hand-hold, which does duty for a handshake, the two went at it with will. Unfortunately they were rather unevenly matched. With their hands they were more or less on an equality, but in toot play one had undoubtedly the best of the game. One professor did little more than offer to kick the other’s shins, or the worst dislocate his knee, while the better man got in a corkscrew kick in the right ear, flicked off a bit of the left eyebrow, disarranged the folds of his opponent’s sash, and hurt his ankle all in one comprehensive chahut. In the third round the better man got in a kick on his opponent’s right breast that sent him to ground, and as nearly as possible knocked him out.

I believe that Mr. Slater is going to pit, or has pitted, English boxers against the Frenchmen, and it will be interesting to see the result. A man who knows as much about boxing as any amateur in this country was sitting in front of me at this press rehearsal, and his opinion was that Lancashire lad would be the best man to set against a Frenchman, for up North they are handy with feet as well as hands. If the evening show is what was put before us, we should say that the preliminary work is tedious, the actual contest decidedly interesting.

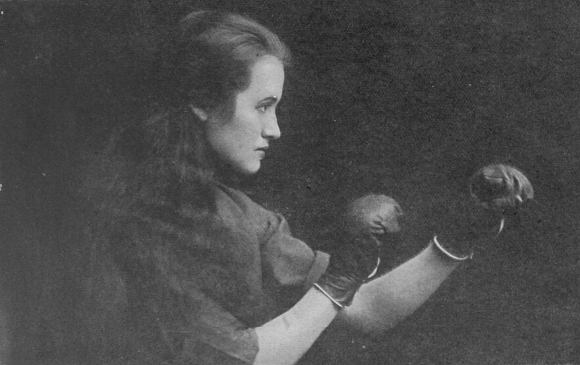

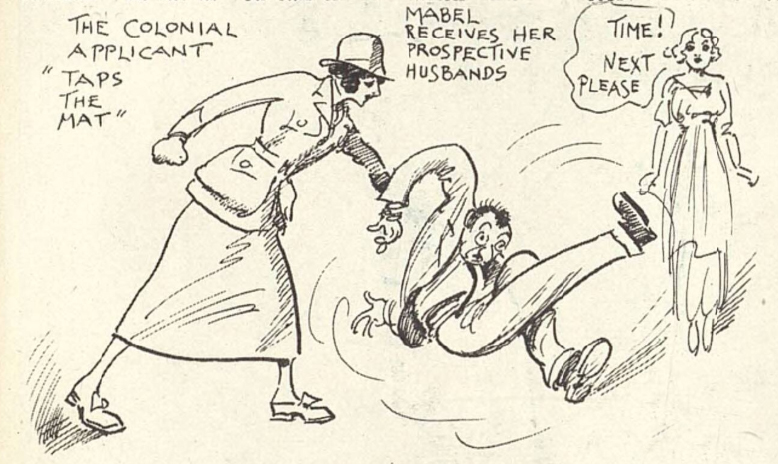

Actress Doris Lytton puts up her dukes as Maude Bray, a supporting character in the 1917 theatrical farce Wanted: a Husband. Hilarity ensues when one of Maude’s friends advertises for a husband to spark some ideas for her new novel.

Maude – a “strenuous woman” who is well-trained in boxing and jiujitsu – volunteers her services as a “chucker-out” (Edwardian-vintage slang for a bouncer). At one point in the play she deals handily with a “colonial” would-be suitor who is making a pest of himself:

This was not the first time that the Japanese art of unarmed combat had been associated with “chuckers-out”. Some reviewers of E.W. Barton-Wright’s early jiujitsu displays commented that they could conceive of no other lawful use of the art, much to Barton-Wright’s indignation.

When E.W. Barton-Wright introduced Bartitsu at the turn of the 20th century, the English (or, at least, the middle-class London) bias against kicking was well-established. The reasons for that bias are not, however, well understood. It may simply have been that the popularity of boxing engendered a general assumption that a “fair fight” was to be fought with fists alone, and thus that any use of the feet in a fight was brutal and “unmanly”.

Nevertheless, kicking folk-sports are well-documented in several regions of England, some dating back at least as far as the 16th century. These styles included several variations depending on local custom and time period; some were contests of agility and endurance in which low-kicking was the only legal technique, and others were styles of wrestling that allowed low kicks along with foot-sweeps and trips. The best-known historical variant today was known as purring and was introduced to the United States during the late 1800s, primarily via Cornish miners; another style is currently practiced as part of the revived Cotswold Olympicks, as seen here:

The anonymous author of the following article from the London Daily News was clearly not aware of the prevalence of English kicking sports. He does, however, offer an interesting description of a Lancashire variant called “puncing”, a term that may well be a cognate of “purring”.

The moral climate of middle-class England during the 1880s was very much in favour of the “civilising impulse” that had by then suppressed duelling and even pugilism. Typically of London-based commentary on kick-fighting during this period, the author takes a disapproving tone, conflating the practice of kicking as rough and tumble sport with street assaults by “cornermen” (gangsters) and even with domestic violence.

We have already commented on the sentence which Lord Justice Brett recently passed upon two Lancashire kickers, and on the circumstances of the crime which provoked that severe but most just punishment. The prevalence of this peculiar form of brutality, however, in Lancashire—or rather in parts of it—is a sufficiently remarkable fact to deserve more attention than that somewhat fitful interest which occasional cases excite.

It is not more than three or four years since a similar outrage first attracted the notice of Londoners and residents of the South of England generally. Although there is unfortunately a good deal of brutality all over England, it cannot said that any particular form of it prevails remarkably in districts other than Lancashire. That “wives are made to be trampled on” is a maxim which is taken literally by ruffianly husbands all over the country as it is uttered metaphorically by enraged and slightly-shrewish wives. Fists, though the scientific use of them is sadly on the decline, are too frequently employed for the purpose, not of self-defence, but offence of a very definite and inexcusable kind.

But the Cornish miner, the Dorsetshire labourer, and the Sussex or Wiltshire shepherd do not usually confine themselves to any special method of avenging themselves against their enemies or giving vent to their feelings. Even in the “Black Country,” the coal districts of Durham and Northumberland, the manufacturing towns of Yorkshire —though in the first two, at any rate, a sufficiently unpolished code of manners prevails —neither kicking nor any similar practice has been brought the level of fine art.

Lancashire – and not the whole of the county, but only in certain of its large towns—stands alone in the rather unenviable possession of this “specialty.” In the towns in which kicking does most prevail, it is practised on a very much larger scale and with very much more precision than the stranger who merely reads a case now and then would suspect. It may perhaps news to some people that kicking does not come by nature, though a little practice at the game of football soon will convince them of the fact. Neither foot nor hand will strike heavily aud accurately without a considerable amount of education; and, as the foot is as used for fewer purposes than the hand, its unhandiness (if an unavoidable pun may be allowed) is far greater.

The Lancashire kicker therefore practises his unamiable art from early age. But in truth he does not call it— at least in its finer forms—kicking. The proper term is “puncing,” and the highest branch of art is a “run punce.” It is, indeed, in good running kicks that the great difficulty of the more harmless game consists, and it is not surprising to find that, in the kicking of men and women, the same obstacles to perfection are found. Practice, however, makes both the Rugby boy and the Lancashire corner-man perfect; the latter, like the former, beginning at a very early age.

It is not to be supposed that the carnivals of brutality which culminate in twenty years’ penal servitude occur constantly, though their occurrence is only too frequent. But lesser opportunities for the practice of the art are probably at least as frequent as opportunities for the display fistic skill were not very many years ago. The alleys and closes of certain Lancashire towns, the corners of the streets, and the doors of the public-houses are frequently the scenes of milder skirmishes, in which this unlovely version of the exercise called in French savate is brought into play.

The heavy clogged boot which is usually worn in these districts has sometimes been taken to be a contributory cause of the practice, on the well-known principle of the connection between the means to do ill deeds and the doing of them. It is, course, clear that whether this is so or not, the boots are a very important factor in the question. Moreover, whatever may be thought about the origin or causes, the fact of the existence of the custom is quite unquestioned. It is an extremely local one, and there are Lancashire towns in which it is possible to reside for months and years without seeing or hearing anything of the practice.

But, on the contrary, there are others in which it is rife, and where, if murder is not done frequently, it is only because the “puncer” is a sufficiently skilful and accomplished practitioner to able to inflict grievous bodily harm without running the risk of the last penalty of the law.

If it is asked what the public opinion of the class which chiefly indulges in this brutal pastime is on the subject, the question is not an easy one to answer. Such public opinion on such points is never very easy to get at. But it would seem to the effect that “puncing,” though not exactly a laudable amusement, is at least not more brutal nor revolting than fighting with the fists. We are not concerned to indulge in any casuistry as to the two exercises. But it may be at least pointed out that even noted bruisers do not generally run amuck through the streets of a town, getting the heads of the casual public into Chancery, and performing the other operations to which the picturesque and metaphorical, though slightly obsolete, terms of the ring are applied.

It takes two to make a fight, in the old sense. In the literal sense, doubtless, it takes two to make the amusement which is the corner-man’s delight. But as in love, in puncing—there is one who punces and another who very unwillingly allows himself to be punced. The highest delight of the puncer, indeed, appears to be to hunt in company, and to toss the victim from boot to boot with a cheerful precision which has something indescribably diabolical about it to those who have not been born and bred to the manner.

The great object of kicking of this kind appears to be the display of skill and the enjoyment of an invigorating pastime, much more than the punishment of injuries or the solace of an irritated temper. Yet, it would appear that in the kicking districts puncing is sometimes regarded by respectable persons as a legitimate, though perhaps extreme, method of showing displeasure. Occasionally in a Lancashire story the villain meets with chastisement in this form, and the agent is not held up to anything like the moral reprobation which would attend the act elsewhere.

Of course, all this shows the need of a very decided reformation of manners; but this reflection, which everybody will agree, leaves untouched the strangeness of the fact that in one district, and in one district alone, of the United Kingdom this peculiar form of brutality has attained something like the proportions and the vitality of an institution. There are no particular elements in the population of the county of Witches which are not present elsewhere. Drunkenness is, unfortunately, by no means confined to Lancashire, and, though the dreary appearance of but too many of her towns might fancifully supposed to roughen the manners of the inhabitants. Yorkshire and Warwickshire, Northumberland and Durham, not mention Glasgow and the towns of the Scotch black country, can fearlessly enter the lists with the blackest town in Lancashire in this respect. The sociologist, who must have a theory, is therefore thrown back upon the boots.

But, whatever may have been the beginning of the practice, whatever may have been the reasons of its continuance and spread, there can be no two opinions about the desirability of its speedily coming to an end. To the antiquary it may possibly be an interesting subject tor investigation and discussion, but to the contemporary historian and student of manners it is anything but satisfactory. There is a certain glib way talking about “relics of barbarism”; but this particular habit, though it is certainly worthy of any barbarism that ever existed, would seem to have grown up in the full civilization of nineteenth-century England.