- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 11th September 2018

By Tony Wolf

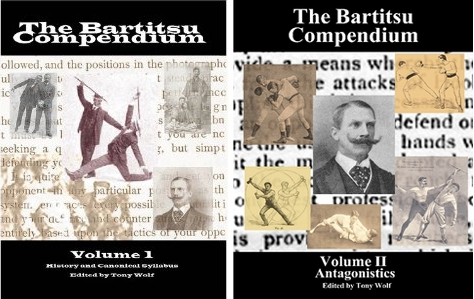

This article offers a brief “history” of the Bartitsu revival movement, especially via the production of the two volumes of the Bartitsu Compendium in 2005 and 2008.

The advent of the Internet during the late 1990s facilitated contact and communication in innumerable special interest fields, very often among individuals and small groups that had been working in relative isolation for years. The newfound ability to “meet” fellow enthusiasts from all around the world online dramatically expanded and accelerated many of these fields; it was, to put it mildly, a heady time.

In the martial arts sphere, the esoteric practice of reviving previously extinct fighting styles received an especially strong boost during this period. The Bartitsu revival began as part of this new movement, originally via the Bartitsu Forum Yahoo Group email list, which was founded by author and martial artist Will Thomas in 2002, almost exactly one century after the original London Bartitsu Club had closed down.

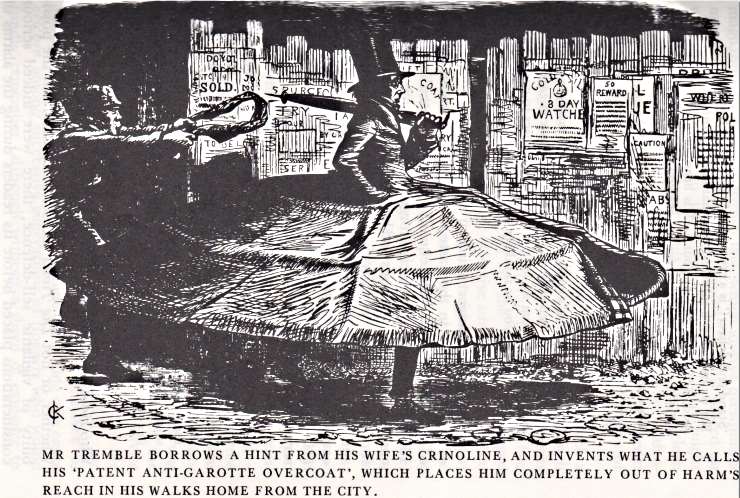

Within about three years, members of the international Forum – which had quickly and informally morphed into the Bartitsu Society – had tracked down a vast quantity of archival information related to E.W. Barton-Wright’s martial art. Most notable were Barton-Wright’s article series for Pearson’s Magazine, which had been discovered by the late British martial arts historian Richard Bowen and which were first broadcast online via the Electronic Journal of Martial Arts and Sciences website. Many of the characteristics of Bartitsu revivalism, including the concepts of “canonical” and “neo” Bartitsu and the essentially open-source nature of the revival itself, were likewise defined during this period.

By early 2004, we had so much information that it seemed fitting to try to get it into a publishable format, if only for the convenience of the (still) relatively few people who had taken a strong interest in the subject. Also, though, there was a growing sense that E.W. Barton-Wright had not yet received due recognition. The more we were learning about his life and fighting style, the more it seemed that he should be acknowledged as a martial arts pioneer and innovator. Therefore, the decision was made to dedicate any profits from the book to memorialising Barton-Wright’s legacy.

Because the potential readership seemed so small and specialised, we realised that the Bartitsu Compendium was unlikely to appeal to traditional publishers. Therefore, we decided to take advantage of the then-relatively new POD (Print On Demand) technology, which would allow individual copies of the book to be automatically printed and shipped as they were ordered.

Volume 1 of the Bartitsu Compendium – which was eventually subtitled “History and the Canonical Syllabus” – was compiled as a group labour of love. I volunteered to edit and generally steer the project and numerous others produced original articles, tracked down ever more obscure sources in European library archives and second-hand bookstores, manually transcribed print into electronic text (OCR technology was not then what it is now) and lent their talents to translations from various foreign languages (likewise re. translation software).

The compilation and editing process took about a year, and then the book was officially launched at a function held in an Edwardian-era meeting room in the St. Anne’s Church complex in Soho, London, literally a stone’s throw from the site of the original Bartitsu Club in Shaftesbury Avenue. A simple table display included a bouquet of flowers, a straw boater hat and a Vigny-style walking stick, along with print-outs of the various chapters. Ragtime music played quietly in the background.

I offered a short lecture on the history of Bartitsu and a demonstration of some of the canonical techniques, followed by a champagne toast to the memory of E.W. Barton-Wright. Guests were then invited to mingle and peruse the print-out chapters (and, if they wished, take them as souvenirs).

To our surprise, the first volume of the Compendium sold well and, in fact, it was Lulu Publications’ best-selling martial arts book for a number of years. Funds from those sales supported the first three Bartitsu School of Arms conferences (in London, Chicago and Newcastle, respectively) and paid for a Bartitsu/Barton-Wright memorial that became part of the Marylebone Library collection, among other projects.

The Bartitsu revival proceeded and grew, with increasing numbers of seminars and ongoing courses being established. By 2007 it was clear that we needed a second volume, presenting resources that went beyond the canonical material and into the corpus of material produced by Bartitsu Club instructors and their first generation of students.

Volume 2 was a more complicated undertaking because it involved cross-referencing over a dozen early 20th century self-defence manuals, almost all from within the direct Bartitsu Club lineage, with the aim of synthesising a complete neo-Bartitsu syllabus. Individual techniques were gathered from multiple sources and carefully assessed, omitting redundancies and duplications while retaining useful variations. We also wanted to avoid developing a fully standardised, prescriptive curriculum, in favour of allowing individuals and clubs to choose their own “paths” through the various techniques and styles that went into the Bartitsu cross-training mix. Further, the lessons of volume 2 were joined together by a set of technical and tactical principles or “themes” redacted from the writings of E.W. Barton-Wright.

Again, the production of the book was very much a team effort, requiring the locating, scanning, transcribing etc. of a wide range of antique self-defence books and articles.

The second volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (subtitled “Antagonistics”) was launched in 2008, and proved to be very nearly as popular as Volume 1. The Compendia have formed the backbone of the Bartitsu revival since then, especially during the “boom time” of roughly 2009-13, which was engendered by the massive popular success of the action-packed Sherlock Holmes movies and consequently by substantial media, pop-culture and academic interest in Bartitsu.

There are currently about 50 Bartitsu clubs and study groups spread throughout the world and many of the old Bartitsu mysteries have either been solved outright or satisfactorily mitigated through educated guesswork. Although it will never be the “next big thing” in the martial arts world, all signs point to Bartitsu continuing as a niche-interest study for those who spend about equal time in the library and in the dojo.