- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Friday, 21st January 2011

Beginning in early November of 1898, Georges D’armoric presented a series of displays of la boxe Français at London’s Alhambra music hall. The Alhambra exhibitions are particularly interesting insofar as they reveal the sentiment of late-Victorian London audiences towards “exotic” arts of self defence, and in that they closely proceeded E.W. Barton-Wright’s efforts to popularise Bartitsu, which also included displays at the Alhambra.

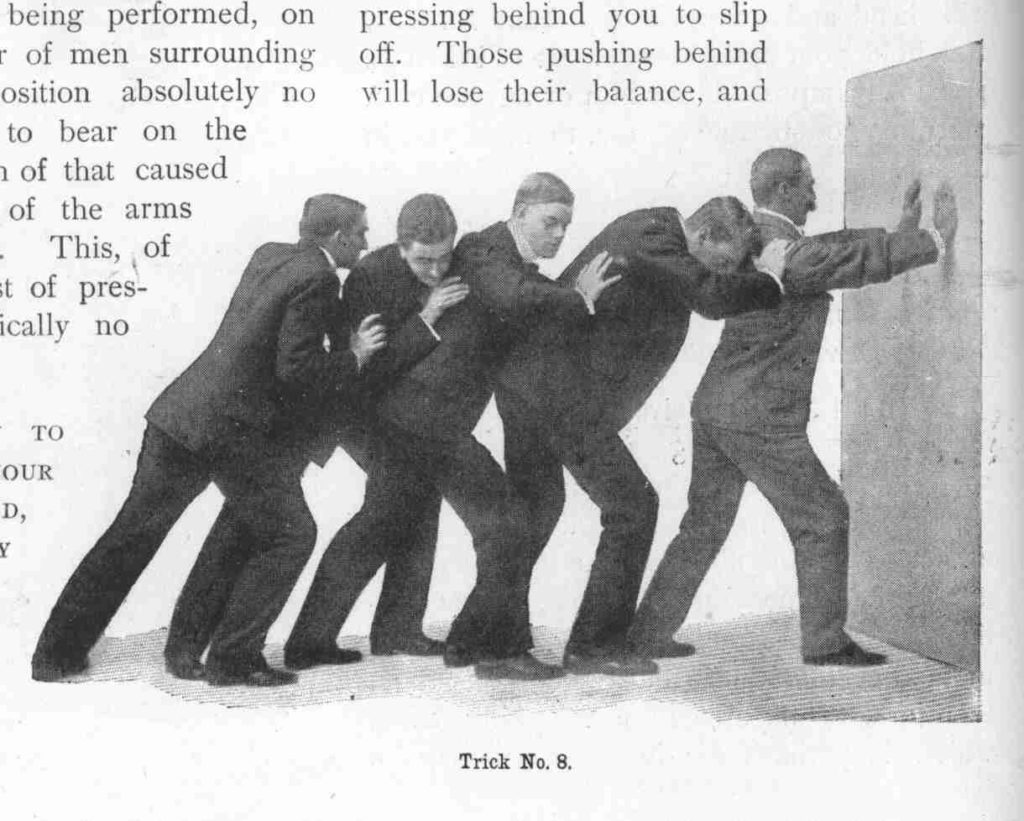

D’armoric evidently intended his exhibitions to educate the British public as to the virtues of “fencing with four limbs” and stick fighting, both as gentlemanly athletic accomplishments and as practical means of self defence. Earlier that year, he had published a booklet entitled Les Boxeurs Français: Treatise-argumentative-on the French method of the Noble Art of Self Defence, which put forth his case in erudite terms.

Faced with the music hall-going public’s insatiable demand for novel entertainments, however, Alhambra manager C. Dundas Slater’s promotion may have rather sabotaged D’armoric’s high-minded goals. Quoted in an article in the London Daily Mail of October 31, Slater said “the audience will go into fits of laughter, as the show is one of the funniest in the world”.

The Daily Mail article continued:

It is hardly likely that (D’armoric’s) efforts will meet with much success, and the main reason is that this really is the country of sportsmen who look upon men who kick as a degrading and cowardly set of curs. But for all that, they will go to the Alhambra to see “Les Boxeurs Francais”, just for the fun of the thing. Whether or not they will have much sympathy for the professors of the Chausson from “gay Paree” is quite a different matter.

The origins of the middle-class, urban Anglo-Saxon bias against kicking are obscure. Striking an opponent with the feet had long been banned by the conventions, if not literally the rules, of boxing. Neither the revised Rules of the London Prize Ring nor those dedicated to the Marquis of Queensberry specifically prohibited kicking, presumably because it was simply taken for granted that boxers would not kick. Certainly, late-Victorian literature makes much reference to the act of kicking an opponent as being “unmanly”, “brutal”, etc.

At least one British method of antagonistics had cultivated the art of kicking, though by 1898, the fearsomely weaponised shoes of rural Devonshire wrestlers, which had played merry havoc with their opponents’ shins in bloody purring contests throughout the first three-quarters on the 19th century, had become the stuff of folk memory. Even during their heyday, when chanced upon by literate urbanites who deigned to record these matches for posterity, the gory mess that was made of Devonshire wrestlers’ lower legs seem to have inspired greater revulsion than the “spout of claret” occasioned by a boxer’s stiff left lead-off or right cross-counter. Ultimately, it is likely that kicking fell out of fashion due to the same civilising impulse that eventually replaced bare-knuckle prize fighting with gloved boxing.

Whatever its cultural origins, by the 1890s the English resistance to kicking was entrenched enough to be remarked upon by several reviewers of the Alhambra exhibitions:

(…) the whole business appears too opposed to our insular ideas of boxing to excite any real interest in the performance.

(…) the British portion of the audience look on with amused toleration, which in the gallery sometimes finds voice in rough and ready criticism. Looked at as an exhibition of graceful agility, the show is a good one, but taken as a serious exposition of a means of self-defense, it seems scarcely worthy of the attention bestowed upon it.

There were also more technical objections:

Setting aside our insular prejudice against kicking, there remains the objection that in nine cases out of ten, despite the marvellous balancing power of these French boxers, the kicker, as soon as he raises his foot a certain distance from the ground, weakens his defense immeasurably. The comparative slowness of the action in striking with the foot, as compared with the fist, together with the fact that much of the force of the blow is spent in secondary movements, also militate against the punitive effects of the art. Nevertheless, the exhibition is an interesting one (…)

This context may help to explain Barton-Wright’s own comments on the kicking content of his Bartitsu curriculum. He took pains to distinguish the kicks practiced at the Bartitsu Club from “the French style”, but omitted to explain what the difference was; given his strong preference for self defence-oriented techniques, he may have preferred to concentrate on low kicks over the more gymnastic high kicking style that was displayed by D’armoric and his colleagues at the Alhambra.

Two years later, the Alhambra exhibition was cited in W.T.A. Beare’s article Antagonistics: A Comparison of Some Methods of Self Defence for Sandow’s Magazine. Perhaps this passage is revealing as to the curious bias shown by earlier reviewers, and which was subsequently repeated by British boxers and wrestlers provoked by Barton-Wright’s jujitsu challenge contests:

Even if not always openly expressed, there has generally been the inference conveyed by the promoters of these new methods that they are superior to our good old English system of fisticuffs; and such expertness and agility have been displayed by the demonstrators that there is little occasion for surprise if many people have arrived at the conclusion that here was something entirely new, something which would nonplus our professors of the “noble art,” and which, to be fully equipped for attack or defence, we should immediately proceed to at least assimilate and superimpose upon our ancient methods, even if we should not abandon these latter altogether.

Perhaps, given the traditional Anglo-French rivalries, the mere fact of difference was enough to conjure a reflexive antagonism, or an assumption of challenge, in the English audience. If so, then D’armoric’s exhibitions may have struck a cultural nerve as symbols of French militarism.

Beare, however, was fair-minded, and in reviewing both French boxing and Bartitsu as he had witnessed them on the Alhambra stage, he concluded:

If, however, I do not admit the superior excellence of this system of fighting to our English system, I am prepared to concede its value in some respects. Its practice must tend to strengthen the legs and to give a man great command over the movements of his body in almost any position; it will render him more agile, and an acquaintance with its main features will prepare him to resist attack in that form.

It is a maxim with many English trainers and instructors, no matter what the game may be, that it is best to specialise and confine attention to the one thing in hand. The running man must not walk, nor vice versa, and if he be a sprinter he must never run distances. The cricketer must not dally with lawn tennis of golf. The Rugby footballer must never play the Association game, and so-on. So, in boxing and wrestling – but the one system must be practised, for indulgence in other forms will vitiate the style, and render the man slow and tame.

Now, with these propositions I do not at all agree. I do not believe in specialism in sport, and much more does the fairly capable all-round athlete command my admiration than the expert in one form of sport or exercise who is a rank duffer in most others.

It must, of course, be conceded that when a man has set himself to attempt some particular feat, or is matched against others in some special form of contest, he should pay, in the later stages of his preparation, exclusive attention to that one thing; but the true athlete should possess a ground-work of all-round excellence, and should not specialise until he has developed all the powers of his body.

In this particular connection I say that an acquaintance with the various different styles of self-defence is of distinct value to the man who would be a good boxer. He cannot know too much, and, though he may not require to use all his tricks in an actual contest, yet the knowledge that he has reserves to call upon at need in the case of an unexpected attack will lend him increased confidence; and he is much less likely to be taken by surprise if he is already well-acquainted with the tricks of other trades.

E.W. Barton-Wright would have applauded.