- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 24th January 2019

This article from the Dublin Evening Herald of 22 December, 1897 reveals a number of the ingenious mugging and pickpocketing tricks developed by French street criminals. A few years after this piece was written, the term “Apaches” would widely be applied to the criminal gangs of Paris, whose distinctive “gangster chic” would then inspire an international craze.

It is a current opinion in France that the national pickpockets are not at the top of their profession, says a Daily Mail writer.

This honor is reserved, in France, for the light fingered gentry of the English race. The British pickpocket is always referred to in the columns of French newspapers as an acknowledged master of this craft, as a workman of the most subtle skill and refreshing audacity. Compared with him, the native product is admitted a little sorrowfully to be a bungling tyro, whose methods are clumsy and whose daring is dubious. To be robbed by so awkward a practitioner is disgraceful as well as disagreeable, while to be eased of your purse by the former is an insult to your patriotism, in addition to an injury to your pocket.

Curiously enough, Charles Dickens is responsible to some extent for this belief in the superiority of the British pickpocket. His immortal description of the training of the thief has been popularized in France, where people are convinced that Fagin has many able successors to teach the art of picking pockets on the most improved principles.

A few years ago, a long and circumstantial account appeared in a Parisian paper of a professional training school for thieves, which the writer professed to have visited in London. The article, of course, was a pure invention; but there is no doubt that the majority of those who read it accepted it as a gospel truth, and it is an amusing fact that its author received several letters offering him money if you would forward the address of the school. Evidently the French pickpocket is not above learning, so that there is hope for him yet. It may be added the word “pickpocket” has come into general use in France, where it has almost entirely replaced the French term, “voleur a la tire”.

Probably it is slandering the native practitioner to say that all the pockets artistically picked in Paris are rifled of their contents by experts from this side of the Channel. Still, it is a fact that the Parisian thief shows a predilection for strokes of business that demand no particular talent. He is always on the lookout, for instance, for an opportunity of robbing persons who have been drinking, not wisely but too well. In one variety of this operation he is called, in French slang, the “guardian angel .” His role is to get into conversation with the toper, who is induced to accept his escort and his arm. Under these conditions, to strip the befuddled percentage of his belongings is child’s play.

A still simpler method of operating is that resorted to by the “poivrier”. This class of rogue lies in wait for the drunkard who is rash enough to go to sleep on one of the public seats that are common in the larger Parisian thoroughfares. As a rule the poivrier is able to explore the pockets of his victim without danger, but it happens occasionally that his wrist is seized in a tight grip, and he is invited to step around to the nearest police station, the pretended sleeper being a detective engaged in what is technically known as “fishing.”

A more elaborate mode of picking pockets is the “vol a l’esbrouffe. ” In this case at least two confederates are necessary. A street is chosen in which there is a fair amount of traffic. A likely victim having been marked down among the passersby, one of the thieves runs up against him, as if by accident, and, instead of apologizing for his awkwardness, lets fly a volley of abuse. A man who has been nearly upset and then insulted in this way gives the aggressor a bit of his mind, and in his excitement, and amid the gathering crowd, he is very likely not to notice that the second thief has eased him of his purse, his pocketbook, or his watch.

When his mere dexterity is at a loss, the Parisian thief often has recourse to violence. In a general way he is careful not to endanger the life of his victim. With this view he has perfected various modes of attack, which enable him to have his prey at his mercy for a few moments.

The “coup de la bascule”is a favorite expedient for robbers working alone, or “philosophers” as they are significantly termed in French thieves’ slang. Suppose a footpad sees somebody coming towards him in a lonely street. When a yard or two from the victim he makes a dart at him and with his left hand clutches him by the throat. Taken by surprise, the victim instinctively throws his head back. At this instant his assailant forces one of his legs from the ground by encircling it with his own legs, as in wrestling. The man who is assaulted is half tripped up, and naturally throws out his arms and effort to regain his balance.

His position, in fact, is very much that of the person attached to the swing board, or bascule, of the guillotine; hence the name of the coup. While the victim is in this helpless state, the thief with the right hand snatches his valuables and then, giving his man a final push or blow with his knee in the pit of the stomach, sends him rolling into the gutter, after which he himself takes to his heels. To be successful, especially if the victim be strong, this coup has to be carried out with the utmost rapidity and precision, far more quickly, indeed, then can be described.

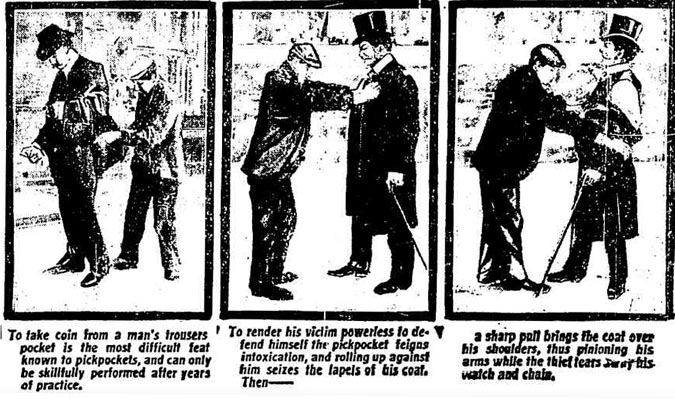

The “coup de la petite chaise” is a sort of a variant of that just given, its object being also to make the victim lose his equilibrium for the few moments needed to allow of the robbery being effected. In this instance the assault is made from behind. The victim is seized by the collar, and the footpad then thrusts his knee into the small of his back, thus offering him what is ironically called a “little seat.” The prey once”spreadeagled” in this manner, the thief gets at his pockets over his shoulder. But the nature of the operation and the aptness with which it is named will be best understood by a glance at the illustration:

Both the coups just described and one or two others similar to them are risky. The chances are all against the victim at the outset, but once he is out of the hands of his assailant, there is nothing to prevent him from screaming for help, or even from turning the tables on his aggressor. A very superior invention from the point of view of the footpad, and a much more dangerous one from that of the victim, is the “coup du pere François .”

In this case two “operators” are necessary. One of them, provided with a stout and long scarf, closes up with the victim from behind, throws the scarf around his neck, turns around sharply, and with a jerk hoists the man he has lassooed upon his back. The confederate then “runs the rule” over the victim, who cannot scream because he is half throttled, and who very probably is in a swoon, the result of strangulation, before the proceedings are terminated.

Ingenious, however, as the contrivance is, it has its drawbacks. The process of strangulation may go to far and be fatal to the victim. Without the least intention of making so ugly a mistake the thieves find themselves murderers, and run the risk of “sneezing into the sack”, which is their picturesque way of saying “being guillotined.”

Such, then, are a few of the methods of the typical Parisian rogue, and those who know the British product will readily admit that for sheer brutality, if not dexterity, his French brother surpasses him easily.

For more details on these and other mugging tricks applied in the mean streets of the French capital, see “Footpads of Paris: How French Thugs Ply Their Thieving Trade”.

Finally, this video demonstrates a number of pickpocketing tricks still in use today, along with common-sense defences against them: