- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Friday, 30th November 2018

Here’s another take on “classic pugilism” sparring, this time by participants at the 2018 HEMAC event in Dijon, France. In contrast to the recently-posted video of a generic mid-late 19th century style, the specific style here is inspired by that of Daniel Mendoza, a famous champion of the late 1700s who is sometimes referred to as “the father of scientific boxing”.

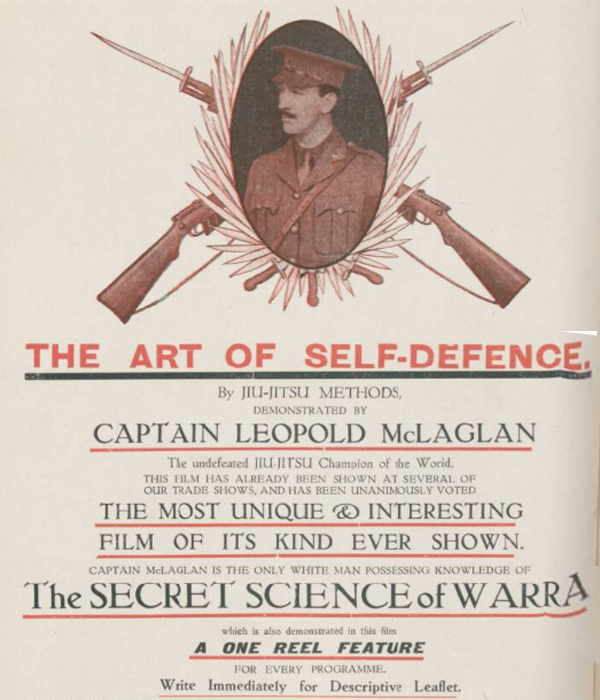

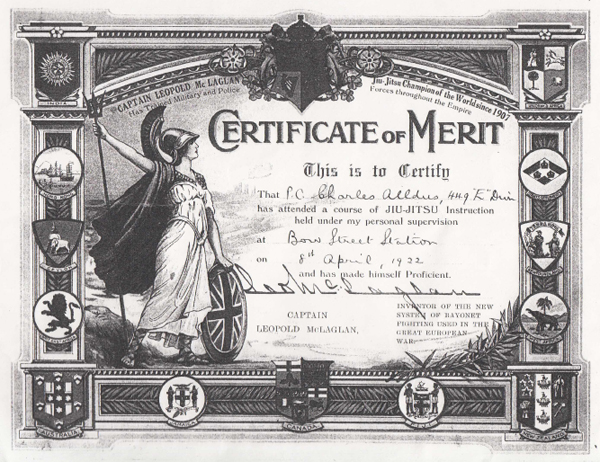

A full-page, colour ad for a 1918 film starring the notorious Captain Leopold McLaglen, whose martial arts misadventures are detailed in this article (note that his name was frequently spelled “McLaglan” in publicity releases, etc.)

Going by the rifle/bayonet theme, the now-lost film probably featured a demonstration of his bayonet fighting system, which he taught to numerous national militaries during the First World War. Giving credit where it’s due, it’s possible that the McLaglen method, which included an emphasis on jiujitsu-like close-combat techniques, may have been better-suited to the grim realities of trench warfare than the more orthodox, “charge and stab” systems taught in most boot camps of the period.

The “Secret Science of Warra” may, conceivably, have been a garbled version of yawara – a term which generally refers to short fist-load stick weapons, but which was also sometimes used synonymously with jiujitsu. Exactly what Leopold McLaglen may have meant by it is anyone’s guess.

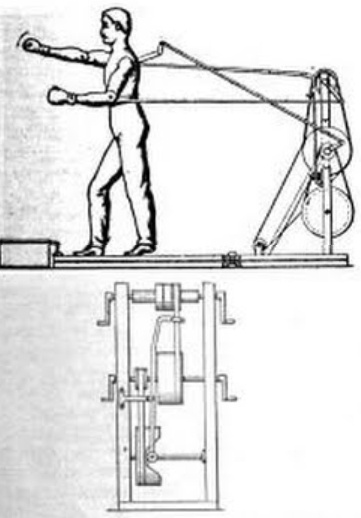

An ingenious solution to the problem of finding (or simply wearing out) sparring partners is detailed in this short article from the Scientific American of July 7, 1906.

To accommodate the needs of the professional boxer, as well as to instruct the novie in the “noble art of self-defense”, Mr. Charles Lindsey, of New Britain, Conn., has invented an automatic sparring machine.

This machine is really a formidable fighter, and has already gained quite an enviable reputation in the many encounters it has had with local talent. Not only does it deliver straight leads and counters, but it varies these with an occasional uppercut, and its blows are rained with a speed and power that are the envy of the professional boxer.

The machine does not “telegraph,” that is, it does not give a warning of a coming blow by a preliminary backward jerk, which is so common to all but the best of boxers. Nor can the opponent escape these blows by side-stepping, because the automaton will follow him from one side to the other. At each side of the opponent is a trapdoor, connected with the base of the machine in such a way that when he steps on one or other of these doors, the machine will swing around toward him.

The arms of the mechanical boxer are fitted with spring plungers, which are connected with crank handles turned by machinery. Separate crankshafts are used for the right and left arms, and they carry pulleys between which an idle pulley is mounted. These pulleys are connected with the main driving pulley by a belt which is shifted from side to side, bringing first one and then the other of the boxing arms into action. The belt-shifter is operated by an irregular cam at the bottom of the machine, and this gives no inkling as to which fist is about to strike.

Aside from this, the body of the boxer is arranged to swing backward or forward under the control of an irregular cam, so that the blows will land in different places on the opponent; for instance, a backward swing of the body will deliver an uppercut. The machine is driven by an electric motor, and can be made to rain blows as rapidly as the best boxer can receive them, or it may be operated slowly for the instruction of the novice. As the machine is fitted with spring arms and gloves, an agile opponent can ward off the blows and thus protect himself.

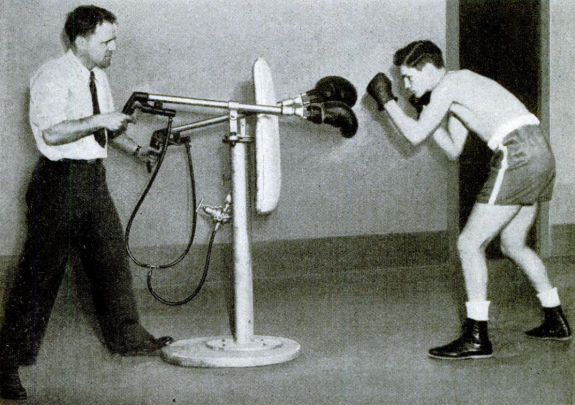

By 1939 a simplified version of the mechanical pugilist, employing trigger-activated pneumatic pistons, was being touted by its inventor, Frederick Westendorf:

C.F. also the various contrivances of boxing armour produced by eager pugilist/inventors around the turn of the 20th century.

An English-language version of the instructional DVD Bartitsu: Historical Self-Defence with a Walking Stick is now available via this link and will become available to the US market via the Freelance Academy Press. The DVD was produced by Agilitas.tv and features Bartitsu instructor Alex Kiermayer assisted by Christoph Reinberger.

The new English-language version is also expected to become accessible as a paid streaming video series via Vimeo in the near future.

We will be offering a review of the entire lesson series soon!

Readers of a certain age may fondly recall the short-lived TV series Q.E.D. (also titled The Mastermind), which screened during the early 1980s. The show featured Sam Waterston as the eccentric former Ivy League professor Quentin E. Deverill, who becomes embroiled in a variety of adventures in Edwardian London. The character of Deverill is reminiscent of Craig Kennedy, the scientific detective who featured in a number of popular short stories written by Arthur B. Reeve during the first decades of the 20th century.

In this scene, during the course of investigating a mysterious disappearance at sea, Deverill attends and debunks a hoax seance, provoking an attack by the “medium’s” henchmen. The hero responds with a very Bartitsuesque combination of fisticuffs and jiujitsu …

Professor Deverill’s active skepticism in the face of spiritualistic chicanery is reminiscent of magician and escape artist Harry Houdini, who famously investigated and exposed numerous fake seances during the 1920s. Houdini later hired a team of undercover private investigators to infiltrate the “ghost racket” scene and report back to him – he nicknamed them “my own secret service” – after which he would publicly expose the mediums during his stage performances.

Although history doesn’t record any Bartitsuesque mayhem in connection with these exposes, members of Houdini’s “secret service” genuinely were caught up in the scuffles that did occasionally erupt between pro- and anti-spiritualists.

Bartitsu founder Edward Barton-Wright himself delved into exposing the tricks of those who claimed supernatural powers via his first article for Pearson’s Magazine in 1899. In “How to Pose as a Strong Man”, Barton-Wright detailed the subtle mechanical and leverage techniques by which vaudeville performers such as the so-called Georgia Magnet demonstrated apparently superhuman strength.

This article from the Sporting Life of 21 December, 1904 includes a possibly-unique report of former Bartitsu Club instructors Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi working together again during the years following the Club’s dissolution. It also represents one of the very first public exhibitions of Japanese unarmed combat by women, presaging both the craze for “jujitsu parties” and the more serious association of jujitsu with the women’s suffrage movement.

The British public are no strangers to ju-jitsu, but it is something of a novelty to see it demonstrated by two daughters of Albion.

Tani’s performances have familiarised many with the commoner manoeuvres, such the fatal arm-lock and the outside-right click, beloved of Jonathan Whitehead, the renowned wrestler of a past generation, but to the Cockney mind ju-jitsu still savours largely of mystery and magic.

In a sense, it does partake of the latter character, and at a demonstration by members of the School of Jujitsu at the Caxton Hall, it was defined as the defence of oneself by sleight of body; the utilisation of your opponent’s strength by taking ingenious advantage of the human anatomy. To accomplish this, the master of ceremonies emphasised the need of studying the art of yielding, as opposed to resisting. Probably this is why wrestlers living outside of Japan have generally shown but limited aptitude for ju-jitsu, the act of yielding being in conflict with their natural instincts.

Those well-known exponents Tani and Uyenishi, were to the fore in illustrating the countless holds, locks, chips, and counters, and a contest between two cheery little compatriots ot theirs in Messrs. Eida and Kanaya raised the audience a high pitch of excitement when “Time!” applied its unwelcome veto.

In the course of the programme two English ladies, Mrs. Watts and Miss Roberts, exhibited some of the tricks of the art. They ware only billed to display of the more elementary points, but they certainly lacked nothing in facility of execution. Mrs. Watts also gave a demonstration with Mr. Eida, whom she appeared to match in proficiency as well as in composure, and – allowing that it was merely an exhibition – this lady showed that she had been an apt pupil.

Another performer was Mr. Miyake, who is much heavier than the other Japanese exponents, though he shares their characteristic agility.

Indeed the whole demonstration, which it is difficult to adequately describe on paper, exemplified in an unmistakable manner that, apart from other advantages, ju-jitsu is invaluable for the cultivation of suppleness. The various turns were of highly attractive order, and testified the sublety which underlies the art. At the same time, the yielding theory is apparently open to qualification. On numerous occasions the exponents undoubtedly practised this principle, but on several others they obviously resisted. This, of course, is only logical, as a policy of “passive resistance” carried to the end must spell subjugation — at any rate, on the mat.

The value of the system is strongly shown in the physiques of its votaries, and the fact of its being a regular part of the Japanese soldier’s training has probably contributed more the success of the Island Empire in Far East campaign than appears on the surface, for it develops the mental well as the physical qualities.

A number of ladies were deeply interested spectators of the proceedings, as were many of the performers’ fellow countrymen.

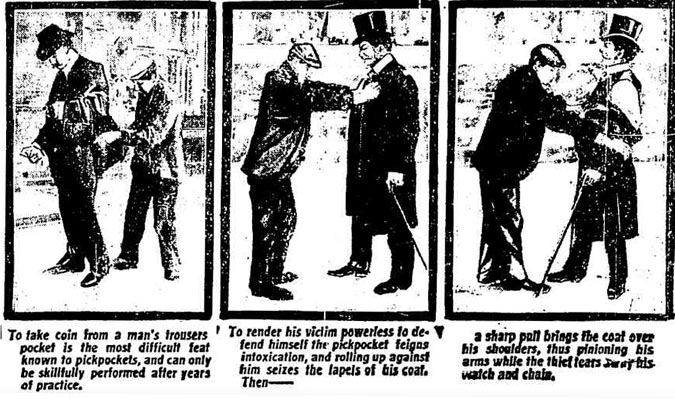

This article from the Dublin Evening Herald of 22 December, 1897 reveals a number of the ingenious mugging and pickpocketing tricks developed by French street criminals. A few years after this piece was written, the term “Apaches” would widely be applied to the criminal gangs of Paris, whose distinctive “gangster chic” would then inspire an international craze.

It is a current opinion in France that the national pickpockets are not at the top of their profession, says a Daily Mail writer.

This honor is reserved, in France, for the light fingered gentry of the English race. The British pickpocket is always referred to in the columns of French newspapers as an acknowledged master of this craft, as a workman of the most subtle skill and refreshing audacity. Compared with him, the native product is admitted a little sorrowfully to be a bungling tyro, whose methods are clumsy and whose daring is dubious. To be robbed by so awkward a practitioner is disgraceful as well as disagreeable, while to be eased of your purse by the former is an insult to your patriotism, in addition to an injury to your pocket.

Curiously enough, Charles Dickens is responsible to some extent for this belief in the superiority of the British pickpocket. His immortal description of the training of the thief has been popularized in France, where people are convinced that Fagin has many able successors to teach the art of picking pockets on the most improved principles.

A few years ago, a long and circumstantial account appeared in a Parisian paper of a professional training school for thieves, which the writer professed to have visited in London. The article, of course, was a pure invention; but there is no doubt that the majority of those who read it accepted it as a gospel truth, and it is an amusing fact that its author received several letters offering him money if you would forward the address of the school. Evidently the French pickpocket is not above learning, so that there is hope for him yet. It may be added the word “pickpocket” has come into general use in France, where it has almost entirely replaced the French term, “voleur a la tire”.

Probably it is slandering the native practitioner to say that all the pockets artistically picked in Paris are rifled of their contents by experts from this side of the Channel. Still, it is a fact that the Parisian thief shows a predilection for strokes of business that demand no particular talent. He is always on the lookout, for instance, for an opportunity of robbing persons who have been drinking, not wisely but too well. In one variety of this operation he is called, in French slang, the “guardian angel .” His role is to get into conversation with the toper, who is induced to accept his escort and his arm. Under these conditions, to strip the befuddled percentage of his belongings is child’s play.

A still simpler method of operating is that resorted to by the “poivrier”. This class of rogue lies in wait for the drunkard who is rash enough to go to sleep on one of the public seats that are common in the larger Parisian thoroughfares. As a rule the poivrier is able to explore the pockets of his victim without danger, but it happens occasionally that his wrist is seized in a tight grip, and he is invited to step around to the nearest police station, the pretended sleeper being a detective engaged in what is technically known as “fishing.”

A more elaborate mode of picking pockets is the “vol a l’esbrouffe. ” In this case at least two confederates are necessary. A street is chosen in which there is a fair amount of traffic. A likely victim having been marked down among the passersby, one of the thieves runs up against him, as if by accident, and, instead of apologizing for his awkwardness, lets fly a volley of abuse. A man who has been nearly upset and then insulted in this way gives the aggressor a bit of his mind, and in his excitement, and amid the gathering crowd, he is very likely not to notice that the second thief has eased him of his purse, his pocketbook, or his watch.

When his mere dexterity is at a loss, the Parisian thief often has recourse to violence. In a general way he is careful not to endanger the life of his victim. With this view he has perfected various modes of attack, which enable him to have his prey at his mercy for a few moments.

The “coup de la bascule”is a favorite expedient for robbers working alone, or “philosophers” as they are significantly termed in French thieves’ slang. Suppose a footpad sees somebody coming towards him in a lonely street. When a yard or two from the victim he makes a dart at him and with his left hand clutches him by the throat. Taken by surprise, the victim instinctively throws his head back. At this instant his assailant forces one of his legs from the ground by encircling it with his own legs, as in wrestling. The man who is assaulted is half tripped up, and naturally throws out his arms and effort to regain his balance.

His position, in fact, is very much that of the person attached to the swing board, or bascule, of the guillotine; hence the name of the coup. While the victim is in this helpless state, the thief with the right hand snatches his valuables and then, giving his man a final push or blow with his knee in the pit of the stomach, sends him rolling into the gutter, after which he himself takes to his heels. To be successful, especially if the victim be strong, this coup has to be carried out with the utmost rapidity and precision, far more quickly, indeed, then can be described.

The “coup de la petite chaise” is a sort of a variant of that just given, its object being also to make the victim lose his equilibrium for the few moments needed to allow of the robbery being effected. In this instance the assault is made from behind. The victim is seized by the collar, and the footpad then thrusts his knee into the small of his back, thus offering him what is ironically called a “little seat.” The prey once”spreadeagled” in this manner, the thief gets at his pockets over his shoulder. But the nature of the operation and the aptness with which it is named will be best understood by a glance at the illustration:

Both the coups just described and one or two others similar to them are risky. The chances are all against the victim at the outset, but once he is out of the hands of his assailant, there is nothing to prevent him from screaming for help, or even from turning the tables on his aggressor. A very superior invention from the point of view of the footpad, and a much more dangerous one from that of the victim, is the “coup du pere François .”

In this case two “operators” are necessary. One of them, provided with a stout and long scarf, closes up with the victim from behind, throws the scarf around his neck, turns around sharply, and with a jerk hoists the man he has lassooed upon his back. The confederate then “runs the rule” over the victim, who cannot scream because he is half throttled, and who very probably is in a swoon, the result of strangulation, before the proceedings are terminated.

Ingenious, however, as the contrivance is, it has its drawbacks. The process of strangulation may go to far and be fatal to the victim. Without the least intention of making so ugly a mistake the thieves find themselves murderers, and run the risk of “sneezing into the sack”, which is their picturesque way of saying “being guillotined.”

Such, then, are a few of the methods of the typical Parisian rogue, and those who know the British product will readily admit that for sheer brutality, if not dexterity, his French brother surpasses him easily.

For more details on these and other mugging tricks applied in the mean streets of the French capital, see “Footpads of Paris: How French Thugs Ply Their Thieving Trade”.

Finally, this video demonstrates a number of pickpocketing tricks still in use today, along with common-sense defences against them: