- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Wednesday, 25th April 2012

Announcing the second international Bartitsu symposium, to take place in the great city of Chicago, USA between September 8th and 9th, 2012. The event is hosted by the Bartitsu Club of Chicago.

- Premise

- Training

- Schedule

- Location and venue

- Field trip to the Hegeler Carus Mansion

- “Susan Swayne and the Bewildered Bride”

- Antagonisticathlon

- Prerequisites

- Please bring:

- Local accommodation options

- Registration

Premise

To preserve and extend the pioneering martial arts cross-training experiments begun by E. W. Barton-Wright at the original Bartitsu School of Arms and Physical Culture, circa 1901:

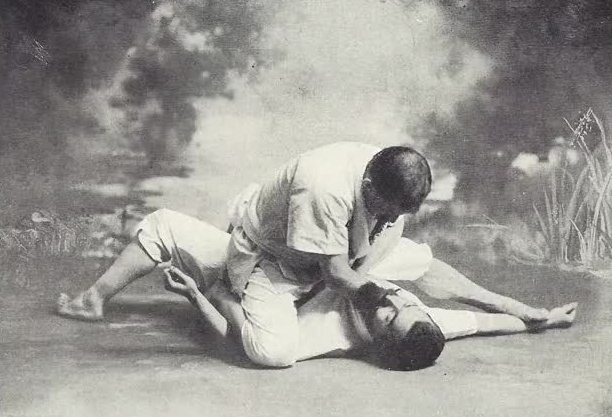

Under Bartitsu is included boxing, or the use of the fist as a hitting medium, the use of the feet both in an offensive and defensive sense, the use of the walking stick as a means of self-defence. Judo and jujitsu, which are secret styles of Japanese wrestling, I would call close play as applied to self-defence.

In order to ensure, as far as it is possible, immunity against injury in cowardly attacks or quarrels, one must understand boxing in order to thoroughly appreciate the danger and rapidity of a well-directed blow, and the particular parts of the body which are scientifically attacked. The same, of course, applies to the use of the foot or the stick.

Judo and jujitsu were not designed as primary means of attack and defence against a boxer or a man who kicks you, but are only to be used after coming to close quarters, and in order to get to close quarters it is absolutely necessary to understand boxing and the use of the foot.

– E.W. Barton-Wright, lecture for the Japan Society of London, 1902

Training

Participants will experience an intense and immersive two days of cross-training and circuit training with fellow enthusiasts, guided by a team of Bartitsu instructors and inspired by the ideal of Barton-Wright’s School of Arms:

In one corner is M. Vigny, the World’s Champion with the single-stick: the Champion who is the acknowledged master of savate trains his pupils in another … he leads you gently on with gloves and single-stick, through the mazes of the arts, until, at last, with your trained eye and supple muscles, no unskilled brute force can put you out, literally or metaphorically.

In another part of the Club are more Champions, this time from far Japan, who will teach you once more of how little you know of the muscles that keep you perpendicular, and of the startling effects of sudden leverage properly applied …

… when you have mastered the various branches of the work done at the Club, which includes a system of physical drill taught by another Champion, this time from Switzerland, the world is before you, even though a “Hooligan” may be behind you …

– “S.L.B.” in the article “Defence Against ‘Hooligans’: Bartitsu Methods in London”, from The Sketch, April 10, 1901

Following the successful model of the inaugural event in London, the 2012 School of Arms will be a “combat laboratory” with participants collaborating as martial athletes, historical scholars and research analysts. Our days will include whole-group training sessions as well as skills-based circuit training and breakout groups concentrating on particular areas of interest. Some cross-training sessions will be team-taught by instructors and others will involve peer-to-peer work.

Instructors and class themes to date (April 22nd – list may be subject to additions and change) include:

Tony Wolf (New Zealand/USA) will be running sessions in combat tactics/biomechanics across each of the Bartitsu skill-sets; twist and segue drills (building upon the stylised canonical Bartitsu sequences through progressive levels of improvisation and resistance as a bridge between set-plays and free-sparring) and c1900 physical culture conditioning exercises.

Keith Jennings will teach aspects of 19th century pugilism (the predecessor of modern boxing) and catch-as-catch-can wrestling, the folk-style which quickly blended with the eclectic jujitsu introduced to the Western world by Barton-Wright, Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi at the Bartitsu Club.

Allen Reed (USA) will concentrate on canonical jujitsu sequences and counters to those sequences arising from resistance by the opponent.

Mark Donnelly (UK/USA) will focus on the principles of Bartitsu as outlined in all of the canonical material. His sessions will demonstrate how canonical Bartitsu outlines tactical approaches to combat at different ranges based on the nature of the threat and the weapons (real or improvised) which are available at that moment.

Schedule

Friday, September 7th: Optional (but highly recommended) field trip to the Hegeler Carus mansion, including historic gymnasium, in LaSalle, Illinois (see details below). Departing from Forteza Fitness at approximately 12.00 mid-day, mansion tour from approximately 2.00-3.30 pm, returning to Forteza by approximately 6.00 pm. Also optional and recommended on Friday night; a meal in Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood, followed by the play “Susan Swayne and the Bewildered Bride” (see below) at 8.00 pm

Saturday, September 8th: Bartitsu training at the School of Arms venue 9.00 a.m. – 12.30 p.m., 1 hour lunch break, training 1.30 p.m. – 6.00 p.m.; reconvene for dinner, discussions and socialising at O’Shaughnessy’s Public House (4557 N Ravenswood Ave, Chicago, IL 60640 – a three-minute walk from the School of Arms venue) from 7.00 p.m. onwards

Sunday, September 9th: Bartitsu training at the School of Arms venue 9.00 a.m. – 12.30 p.m., 1 hour lunch break, training 1.30 p.m. – 4.15 p.m., antagonisticathlon (see below) from 4.30 – 5.45 p.m.; closing, presentation of participation certificates, group photos and farewells.

Please visit the Events.com website for information on other sporting and cultural events taking place in Chicago during September and TripAdvisor.com for details on the Windy City’s many tourist attractions.

Location and venue

… a huge subterranean hall, all glittering, white-tiled walls, and electric light, with ‘champions’ prowling around it like tigers …

– journalist Mary Nugent, describing the original Bartitsu Club in her January, 1901 article for Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture.

The 2012 School of Arms venue is the Forteza Fitness, Physical Culture and Martial Arts studio in Chicago’s popular Ravenswood district.

Specifically inspired by E.W. Barton-Wright’s original Bartitsu School of Arms and Physical Culture, Forteza is one of the very few full-time, dedicated Western martial arts facilities in North America. Old-school brick walls and a soaring exposed-beam timber ceiling enclose a 5000 square foot studio in a c1900 building, which also includes the Gymuseum, a “living museum” of functional antique physical culture equipment.

Please click here to view a fully interactive map of the local area, with the School of Arms venue highlighted. You can also use this map to check routes to and from the venue and accommodation/entertainment options, etc. Note that the Forteza studio is a three minute walk from the Montrose Brown Line train station.

Free, all day street parking is typically available all along Ravenswood Avenue. Please do not park in the small parking lot immediately outside the studio door, as the spaces there are reserved for the adjacent businesses.

Field trip to the Hegeler Carus Mansion

Built in the year 1876, the Hegeler Carus mansion is located in LaSalle, a two-hour journey from downtown Chicago. The 57-room mansion is considered to be one of the finest examples of Second Empire architecture in the American Midwest. It has been the site of numerous historic accomplishments in industry, philosophy, publishing and religion. For eleven years during the late 19th century, the mansion was the base of Japanese scholar D. T. Suzuki’s efforts to communicate Zen Buddhism to the Western world.

Of particular interest to practitioners of Bartitsu and c1900 physical culture, the Hegeler Carus mansion houses what is believed to be the world’s oldest private gymnasium. The turnhall (German, “gymnastics room”) still contains its original equipment, including wooden Indian clubs and dumbbells, “Roman rings” suspended from the ceiling, gymnastics poles, climbing ladders and an extremely rare “teeter ladder” device. D.T. Suzuki himself exercised there.

School of Arms participants are invited to accompany Tony Wolf, a member of the Hegeler Carus Foundation’s advisory board, in a fascinating guided tour of the mansion and historic gym.

Susan Swayne and the Bewildered Bride

After returning from LaSalle, School of Arms participants will be welcome to join us for a meal and a show! The play Susan Swayne and the Bewildered Bride concerns the adventures of the “Society of Lady Detectives” in late-Victorian London, and has been described as “Mary Poppins meets the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen”. They’ve been getting great reviews and the fight choreography includes fencing, knife fighting and, yes, Bartitsu!

The theatre is in Lincoln Square, a five minute drive or easy 12 minute train trip from Forteza.

Your School of Arms registration fee covers your ticket to see “Susan Swayne”. Please let us know whether you will be attending the show, towards our making an accurate group booking.

Antagonisticathlon

Combining fun with challenge, the antagonisticathlon is a fitting final event for the 2012 Bartitsu School of Arms. Participants represent Victorian-era adventurers fighting their way through a gauntlet of obstacles and “assassins”, inspired by Sherlock Holmes fending off Professor Moriarty’s henchmen in The Adventure of the Final Problem. Although the antagonisticathlon is not a competition, “style points” may be awarded at the judges’ discretion …

Prerequisites

In order to ensure good progress for the whole group throughout the School of Arms, certain technical skills are required as prerequisites of participation. These include:

- basic ukemi (breakfalling) – you must be able to comfortably and safely fall backwards and/or sideways to the left and right from a standing start

- basic boxing – you must be able to comfortably and safely punch a hand-held, padded striking target with either fist

- fitness – this will be a physically intense event and you should be in good general physical condition. We will be active all day, each day. People with significant physical challenges should contact the organisers for advice before committing to attending the event

Please bring:

- A large water or sports drink bottle

- Exercise clothing resembling 19th century physical culture kit (typically, a plain, form-fitting t-shirt or tanktop/singlet and either yoga pants, fencing pants or gi pants in any combination of the colours black, white, navy blue, maroon or grey)

- A pair of exercise shoes to be worn during training; please note that outdoor shoes are not permitted on the Forteza studio floor

- A sturdy crook-handled walking stick and/or rattan rod approximately 36″ in length, with any sharp or rough edges smoothed away

Participants in the antagonisticathlon are encouraged to wear clothing evocative of the Victorian period, if practical.

Fencing masks, gi jackets and sashes, boxing gloves, hand protection for stick fighting, mouth guards, additional body protection (knee/shin pads, groin guards, etc.) are not required, but will be welcome if you can bring them. A limited number of rattan canes, fencing masks and other items of protective equipment will be available for training and sparring purposes.

We suggest that you bring a light jacket or sweater. Average temperatures in Chicago during early September are pleasant, ranging from a high of 74°F (23°C) to a low of 55°F (13°C). The risk of rainfall is low.

Local accommodation options

This map details numerous accommodation options in the vicinity of the Bartitsu School of Arms venue. Please note that participants are responsible for arranging their own accommodation; this expense is not included in the 2012 School of Arms registration fee. In selecting accommodation, please note again that Forteza Fitness is very close to the Montrose Brown Line train station.

Update: members of the Bartitsu Club of Chicago are able to offer free homestay accommodation to School of Arms participants on a first-come, first serve basis. Please contact tonywolf@gmail.com to discuss the homestay option.

Registration

The 2012 Bartitsu School of Arms is a boutique symposium hosted by the Bartitsu Club of Chicago. The event is strictly limited to 30 participants aged 18 years and older.

The registration fee for the event is US$120.00 (€91.00, £74.00). You can register and pay online (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express and PayPal) via this link:

If you wish to register for a single day, please send US$60.00 via PayPal to tonywolf@gmail.com , clearly noting whether you are booking for Saturday or Sunday training.

Payment may also be made in cash or by credit card on the day, but it is crucial in these cases to make advance contact via tonywolf@gmail.com to ensure that there will be a free space.

Please note that your registration fee goes towards operational expenses associated with running the School of Arms. Participants are responsible for arranging for their own accommodation and buying their own meals and drinks.

We hope to see you soon in Chicago!