- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Saturday, 14th August 2010

(With thanks to the late Richard Bowen as well as to John Bowen and Joe Svinth.)

William E. Steers is one of the “mystery men” of the early British jiujitsu scene. His name appears in connection with those of many more famous figures – London Budokwai principal Gunji Koizumi, judo founder Jigoro Kano, soldier/author/journalist E.J. Harrison and pioneering challenge wrestlers Mitsuyo Maeda, Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi.

Unfortunately, few biographical details are available, and those that are offer a scattershot impression of William Steers. We know that he was born circa 1857. Contemporary sources noted him as having been an auditor for the British Ministry of Munitions; he was also an “extraordinary scholar” and a member of the Society of Arts. By the age of forty he had evidently travelled widely in various capacities throughout the British Empire, possibly as far away as New Zealand.

In 1903 Steers set sail for Japan, where he befriended E.J. Harrison and began training in jiujitsu. Returning to London the following year, Steers joined the Golden Square dojo of former Bartitsu Club instructor Sadakazu Uyenishi. There he made the acquaintance of Gunji Koizumi, who had recently arrived from Liverpool where he had been briefly affiliated with the highly dubious Kara Ashikaga School of Jiujitsu. During this period Steers may also have studied with Mitsuyo Maeda, a prominent competitor on the professional wrestling circuit.

Circa 1909, Steers commissioned the design and construction of an extraordinary house in the Surrey Downs. As it was built atop one of the highest hills in the Tandridge district, near the town of Caterham, Steers named his new home “Hilltop”.

Created by the architectural firm of Parker and Unwin, Hilltop featured a unique blending of Japanese aesthetics with those of the then-burgeoning English Arts and Crafts movement. According to an article in The Craftsman journal of 1910:

By a life spent in close study of the characters and customs of many nations, perhaps more especially of the Japanese, he has gained that breadth of outlook which much travel alone can give, and has come to feel that we have much to learn from the older civilizations of the East, civilizations which on the other hand, we of the West are beginning to mar.

It’s likely that the gi-wearing figure standing in the doorway in the following picture is Steers himself:

The interior of the house featured a graceful combination of Asian and European motifs:

However, by far the most unusual feature of Hilltop was its gymnasium, which melded the typical features of an Edwardian physical culture studio with those of a Japanese martial arts dojo.

Quoting the architect:

… when Mr. Steers came to settle in England it was his wish to do this in a home and among surroundings which would make it possible for him to practice and demonstrate to others what he had come to believe in. His position being as follows:—that it is everyone’s first duty to society and to himself or herself to be always in the most perfect health possible. He even goes so far as to say that few of us are justified in being ill, and would put no duty before that of keeping in perfect health, claiming that only when this has been accomplished are we capable of our best in any sphere, and that it is our duty never to give anything short of our best.

Believing in the physical and perhaps even greater mental alertness and agility resulting from the practice of the Japanese art of self-defense, jiujitsu, he would have it taught in our schools and colleges, to our military, naval and police forces. He holds that its practice gives a physical, mental and moral self-reliance which nothing else can.

One of the principal rooms of his house had therefore to be so planned as to give ample facilities for the practice of this art, while at the same time it was not to be spoiled for the many other uses to which it might be put. On the accompanying plans this room is called the gymnasium. It is worthy of careful study from both decorator and athlete.

It was not possible to secure quite as much sunshine in this room as could have been wished, partly owing to considerations for its privacy and partly to the necessary position for the living room. The gymnasium, however, gets all the northeast, east and southeast sun there may be, that is the morning sun, and its use as a gymnasium is almost entirely in the morning. The front of this room being composed of rolling shutters and large opening windows through which one enters onto an exercising lawn, terminating in an open-air swimming bath, necessitated extreme privacy and therefore an aspect away from the road which runs by the south end of the house. The room is carried to the full height of the house—that is, two stories—so, when the rolling shutters, together with the French windows on either side of them and the row of windows above are all open, as is almost always the case, the room is a very high one with practically one side open; in fact, it becomes a three-walled room. This sense of openness and airiness may be experienced which would be unobtainable in a less lofty room, even though as open in front. The floor, like a dancing floor, is carried on springs, and is covered with Japanese reed mats two inches thick. A dressing room and bath are connected with the gymnasium.

In summer, with mattresses thrown down at night upon the reed mats and the front thrown open, this room becomes one of the most delightful sleeping apartments imaginable. The Japanese custom of having no apartments set aside exclusively for sleeping in is one that Mr. Steers holds we might well adopt. Is it not possible that in some of our smaller houses we could frequently with advantage so adapt the furniture in some of the rooms in which part of our daily occupations are performed, that by simply throwing down mattresses and bedclothes when night comes we could sleep quite comfortably? Some claim that it is unhealthy to sleep at night in a room used in the daytime; surely this idea belongs to the days when it was customary to keep all windows closed. In these days when we all appreciate the hygienic value of fresh air and no longer open windows merely to “air the room,” but live with the windows open day and night, this claim can have no significance.

The decoration of the gymnasium was undertaken by Mr. Hugh Wallis of Altrincham. He was asked to go to Caterham, to stand in the middle of the room and imagine he was standing in a green glade or clearing in a forest, then to paint on the rough plaster of the walls the vistas among the trees, their foliage, boles, stems and branches, glimpses of sky and distant landscape, and in the foreground, characteristic woodland flowers in the grass. When the artist reached Caterham, however, the spirit of the delightful Surrey scenery surrounding him took so great a hold of the imagination that he had perforce to reproduce it in his delightfully decorative style. The vistas between the trees widened out and became filled with glimpses of distant country, broadening finally into wide peaceful scenes in the luxuriant Surrey countryside.

According to British judo historian Richard Bowen, Steers shared Hilltop with fellow jujitsuka E. H. Nelson, who had helped to organise their teacher Sadakazu Uyenishi’s “Text-Book of Ju-Jitsu”. Strangely, however, Steers was only to occupy Hilltop for a few years. In 1911 he sold the property and the following year he returned to Japan, where he enrolled at the Kodokan in Tokyo and became a student of Jigoro Kano’s. Kano later described Steers as having been the most earnest foreign student he had ever taught. At the age of fifty-five Steers was awarded the black belt rank in Kodokan judo, being only the second Westerner ever to achieve that rank.

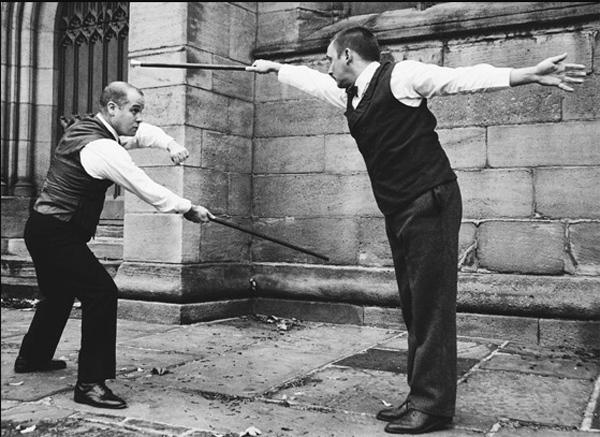

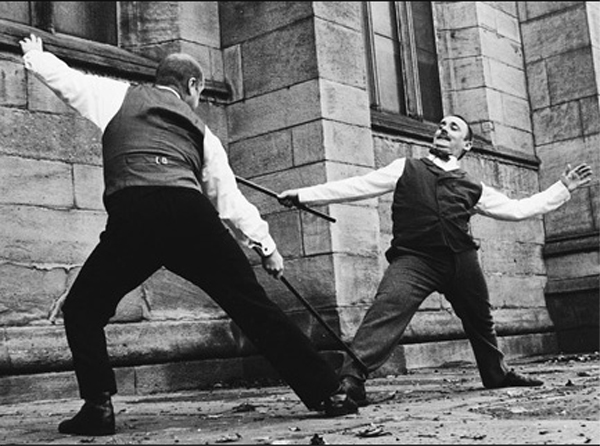

Re-settling in London, Steers continued to display an almost evangelical zeal for judo, most especially for its emphasis on both moral and physical fitness. In 1918, at the age of sixty-one, he gave a speech entitled “A Perfect Manhood, or, Judo of the Kodokwan”. During the lecture he advocated free tuition in judo for almost every English citizen and performed a demonstration of “hand-throws, waist-throws, leg-throws, and lateral and frontal sutemi – a sacrifice for a gain.” This event aroused huge enthusiasm within the newly-founded London Budokwai, whose members sent copies of the text to many hundreds of politicians and educational institutions. Unfortunately, nothing came of their efforts.

Steers became Budokwai member number 52 and went on to become the clubs’ first honourary secretary. He was responsible for introducing his friend E.J. Harrison to the club, and later, the prominent American martial artist and scholar Robert W. Smith.

Steers’ most historically significant accomplishment, though, was that he was instrumental in forging ties between the London Budokwai and the Kodokan. In 1920 the Budokwai hosted a visit by Professor Kano and 4th-dan instructor Aida Hikochi, and thereafter the club officially took up the study of judo. Both former Bartitsu Club instructor Yukio Tani and Gunji Koizumi were accredited Kodokan 2nd-dan black belts, with Tani becoming the Budokwai’s first professional teacher. This shift marked the end of the era of eclectic “British jiujitsu” begun in 1898 by E.W. Barton-Wright, and the beginning of the formal development of judo in the UK.

William E. Steers died in his early 70s during the year 1930.