This gymnasium was part of architect W.W. Boyington’s original design for the Hegeler Carus Mansion, which is located at 1307 7th St, La Salle, Illinois. Spanning the basement and ground levels and dating to the year 1876, the unique design and fittings of this room may represent the oldest surviving example of a private gymnasium in the United States.

The Hegeler Carus gym is also believed to be a uniquely preserved example of a 19th-century Turnverein (gymnastics association) turnhall.

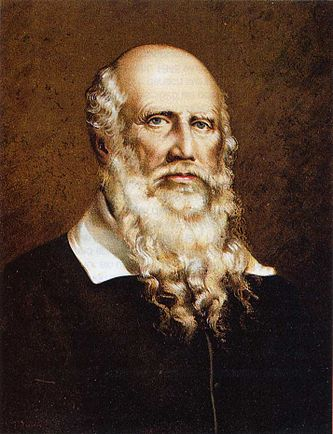

“Turnvater Jahn”

The German Turnverein (“gymnastics association”) was founded in the early 19th century as a confluence of the patriotic and athletic ideals of Freidrich Ludwig Jahn. Born in the year 1778, Jahn, who became known as the Turnvater (roughly, “Gymfather”), was deeply involved in the struggle to liberate Germany from the tyranny of Napoleon I of France. He believed that the union of physical confidence, strength and skill with nationalistic fervor would both equip and motivate German youths to defend their homeland against invaders. In this, he was inspired by the classical Greek and Roman traditions of education, which stressed a balanced approach to physical, intellectual and ethical development.

In 1811 Jahn opened his first Turnplatz, or outdoor gymnasium, training some five hundred young men and boys in physical culture. Although encouraging a spirit of challenging play, Jahn was also known as a strict disciplinarian who insisted upon good manners as well as the perfection of form in physical exercises. When King Frederick William III of Prussia issued a call to arms on March 17, 1813, Jahn and his Turners were among the first to respond, and their fitness and discipline were proved battle-worthy.

After Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, Jahn became dissatisfied with the new German political regime, and spoke forthrightly in favor of the German people being awarded a constitution. His Turnverein movement grew in strength, fervency and influence and by 1818 the German government began to perceive the Turners as a subversive organization. Following the assassination of journalist August von Kotzbue by student radical Karl Sand, who belonged to an organization that had ties to the Turners, the authorities responded by closing Turnverein gymnasia. Later that year, Jahn was arrested on charges of high treason. He was confined for two years and suffered persecution from the authorities upon his release. Despite Jahn’s largely retiring from the political arena to pursue a life of scholarship, this persecution continued until 1840, when Frederick William IV ascended to the throne.

The prohibition against the Turners was repealed in 1842 and numerous new clubs were formed, holding to Turnvater Jahn’s ideals of athletic prowess and nationalistic politics. However, the government remained indifferent to the popular demand for a German constitution and for greater democratic freedom. Public frustration finally boiled over into open revolution in 1848. This conflict divided the Turners into two camps: the conservatives, favoring a constitutional monarchy as well as athletic and social programs, formed by the Deutscher Turnerbund, and the more politically radical Demokratischer Turnerbund, under Friedrich Hecker and Gustave Struve.

During this same eventful year, Friedrich Jahn was again thrust into public prominence as an elected representative of the National German Parliament. However, Jahn’s politics, vitally relevant in defying Napoleon’s tyranny, were now out of step with the more aggressive ideals of many of his followers, and he found himself estranged from the greater part of the movement that he had founded. Withdrawing from the Turners, embittered and misunderstood, Jahn died in Freiburg on October the 15th, 1852.

The “Forty-Eighters“

The 1848 revolution had failed. A large number of prominent revolutionaries, many of them highly educated, socially progressive professionals, left Germany in an attempt to help establish more democratic societies in the New World. Many emigrated to the United States of America and to Canada. Among them were former leaders of the Demokratischer Turnerbund, who quickly established new Turner societies in their new countries, where they became known as the Forty-Eighters.

The first American Turner society was the Cincinnati Turngemeinde, founded by Friedrich Heckler on November 21, 1848. A number of similar clubs were formed over the next several years, uniting as the Turnerbund or National Turner Association during 1850-51. Although there were no legal barriers to the establishment of Turner clubs, the Forty-Eighters did meet with substantial opposition at the social level from the anti-immigrant Native American Party, better remembered today as the Know-Nothing Party, from their practice of demanding that members claim to “know nothing” when questioned about Party activities. As visible representatives of German culture in the United States, the Turners were often harrassed by Know-Nothing Party affiliates.

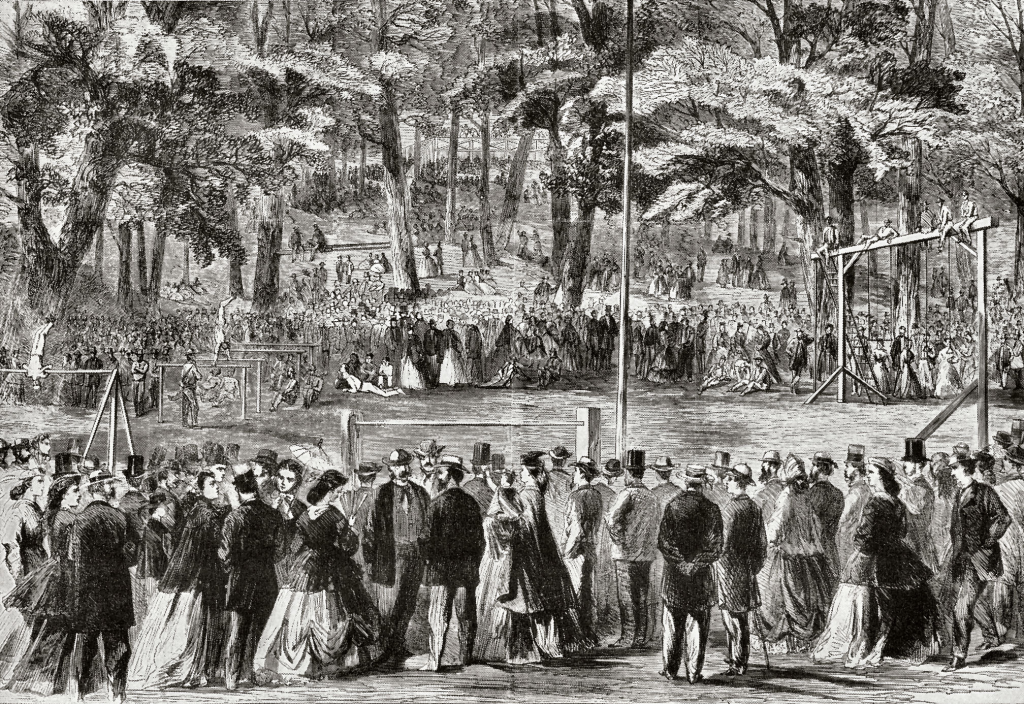

Despite external harassment and internal political difficulties, the Turnerbund continued to grow and staged a series of successful Turnfests (gymnastics festivals) throughout the country.

However, the heated argument between the Northern and Southern states regarding the issue of slavery was quickly reaching a crisis point. The pro-democratic Turners largely aligned with the anti-slavery movement and this led in turn to an increase in clashes with the Know-Nothing Party. One turnfest in Cincinnati was invaded by Know-Nothing affiliates and the ensuing riot resembled a battle. The Turners were well trained in self- defense and were victorious, but some of them were arrested and charged with assault with intent to kill; these charges were eventually dropped.

At a Turnerbund convention in 1855, the majority of Turners officially stood against slavery and thereafter Turner groups frequently served as bodyguards for Abolitionist speakers. Meanwhile, however, the political and organizational disputes between regional Turner societies led to the factionalization of the movement.

In 1860 the Executive Committee of the Turnerbund urged all members to support Abraham Lincoln’s bid for presidency. After his electoral victory, the Turners were thrust into more violent clashes with pro-slavery and anti-immigrant groups; civil war was just around the corner.

The Turners in the Civil War

As they had when King Frederick William III had declared war against Napoleon, the Turners were among the first to enlist for battle. In regions where German immigrants were most populous, entire Union companies were recruited from Turner ranks. Some twenty-four Turner regiments went on to play important parts in the conflict, although the exodus of athletes and organizers into the armed services inevitably weakened the Turnerbund’s cultural and athletic base. However, regional groups continued to organize turnfests and a Turnerbund convention in Washington on April 3, 1865 served to heal many of the rifts that had opened in the movement during the pre-War years.

The defeat of the Confederacy at Gettysburg co-incided with the re-unification and re-invigoration of the Turnerbund, which was also bolstered by a new wave of German immigrants. The relative post-War prosperity of the North, combined with the energy and enthusiasm of the newcomers, many of whom were already trained Turners, saw the American Turnerbund enter an unprecedented period of growth. During the following decade, old turnhalls (gymnasia and social clubs) were revived or rebuilt and new ones were established.

The Hegeler Carus Mansion Turnhall

Among the new generation of Turnhalls was that built in the LaSalle, Illinois mansion of German-American industrialist Edward C. Hegeler, in 1876. A partner in the Matthiessen Hegeler Zinc Company, Hegeler had a large family and had architect W.W. Boyington design a private turnhall in the mansion’s basement.

The Hegeler Carus turnhall was converted into a storeroom during the early 20th century and most of the exercise equipment was stored away in the adjacent basement space, where it remained until 2008, when physical culture historian Tony Wolf paid a visit to the mansion. Recognizing the potentially unique historical significance of the turnhall, he approached the Hegeler Carus Foundation with an offer to locate, identify and reassemble the equipment.

During a family reunion and seminar series arranged by the Hegeler Carus Foundation, Wolf was given the opportunity to search the storage spaces and discovered several key items of exercise apparatus in various states of disassembly. Close examination of the gym’s fittings offered concrete clues as to how and where some of them had originally been arranged.

In 2009 Tony Wolf was appointed to the Advisory Board of the Hegeler Carus Foundation, with special responsibility for the turnhall and its preservation.

Special Features

The mansion’s sports and exercise apparatus collection also includes antique wooden stilts, skis, two extremely early basketball hoops and a set of skittles. Towards extending the turnhall’s collection, the Hegeler Carus trust has also purchased an antique pommel horse and a wooden bowling set.

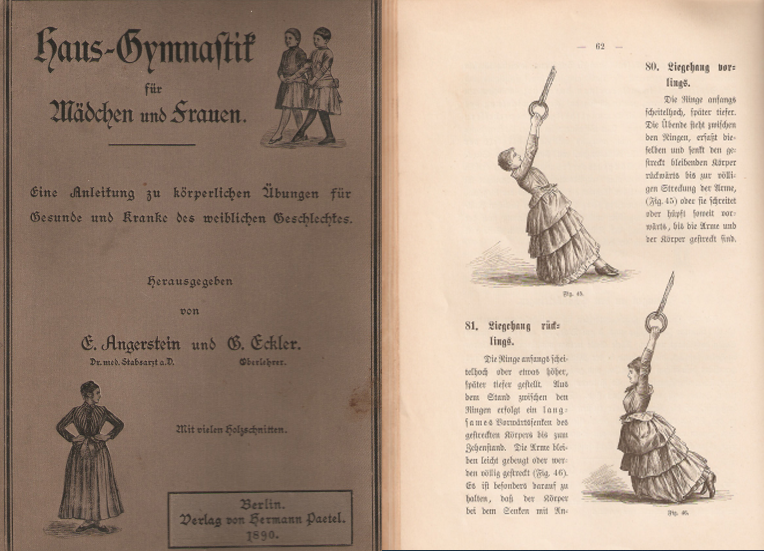

Tony Wolf also discovered a copy of the book Hausgymnastik für Mädchen und Frauen (“Home Gymnastics for Girls and Women”), written by E. Angerstein and G. Eckler in 1888, on one of the mansion’s bookshelves. This book includes instructions and illustrations of many of the types of exercise to be performed on the apparatus housed within the Hegeler Carus mansion turnhall.

The Hegeler Carus Turnhall Today

Once reassembled, the turnhall became a highlight of the regular tours of the mansion operated by the Hegeler Carus Foundation. For a time visitors were able to enter the gym space and examine the equipment, but unfortunately one over-eager patron accidentally pulled the climbing pole from its display moorings, and so now viewings are only available from the stairs and landing. Occasional exceptions can be made by arrangement, as when Tony Wolf demonstrated some of the equipment to a group of Bartitsu enthusiasts in connection with the 2nd annual Bartitsu School of Arms event in September of 2012.

In 2013 the adjustable ladder was damaged by vandals attempting to break into the mansion through one of the basement windows, but luckily the building’s alarms repelled them before any further damage could be done.

At present the gym remains a unique example of a 19th century turnverein-style turnhall and it is believed to be the oldest private gym in the USA, if not the world. While light preservation is carried out as required, long-term plans include the full professional restoration of the gym and its equipment; however, that will be a massively expensive undertaking, as the entire mansion is slowly restored to its former glory.

In the meantime, prospective visitors are welcome to tour the mansion.