- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 10th September 2015

“… a huge subterranean hall, all glittering, white-tiled walls, and electric light, with ‘champions’ prowling around it like tigers …”

– Mary Nugent (January 1901)

There are now approximately forty Bartitsu clubs and study groups around the world, all working to continue E.W. Barton-Wright’s experiments in blending scientific fisticuffs, jiujitsu and Vigny cane fighting. In keeping with the DIY, open-source nature of the Bartitsu revival, every club pursues its own agenda and points of emphasis. But what do we know about the original Bartitsu School of Arms and Physical Culture in London’s Shaftesbury Avenue?

Origins

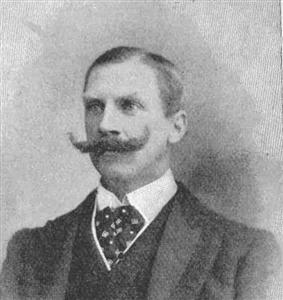

E.W. Barton-Wright began performing jiujitsu displays almost as soon as he returned to London from Japan. At that point, given his birth and early years spent in India, his education in France and Germany and his constant international travels as an adult, he had probably spent many more years living outside of England than “at home”.

Barton-Wright’s demonstration at the famed Bath Club in March of 1899 seems to have been a pivotal event, in that this was probably where he first met William Grenfell, the First Baron Desborough, and Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon. These aristocrats – both of whom enjoyed novel and eccentric athletic pursuits – had the all-important social standing and connections that Barton-Wright needed if he was to make his name in London.

The following month, at the conclusion of Barton-Wright’s two-part Pearson’s Magazine article “The New Art of Self Defence”, he noted that “in the future, all being well, I shall open a school”.

By June of that year, Grenfell was championing the idea of what would become the Bartitsu Club. Socially prominent, athletic, well-liked and an inveterate supporter of many clubs and organizations, he was the natural choice for Club president, with Barton-Wright assuming the role of Managing Director.

A committee of gentlemen

It’s important to bear in mind that early Edwardian London was highly class-conscious and that the notion of a “club” carried a different connotation during that period than it typically does today. It would be unusual for a club to advertise in newspapers, for example, because word-of-mouth recommendations were considered to be more prestigious. Exclusivity, among other things, was taken for granted. Therefore, when Grenfell described the then-nascent Bartitsu Club to reporters in June of 1899, he stated plainly that the idea was:

“… to establish an athletic class for people of good standing, and it seemed to us best to establish it in the form of a club, so as to be able to exclude undesirable persons. So members will be able to come themselves, and to send their children and the ladies of their family for instruction with every assurance that they will be running no risk of objectionable associations.”

Barton-Wright himself offered some clarification regarding what would be considered “undesirable” and “objectionable” in an interview during September of 1901. Replying to the interviewer’s observation that “If you sow this knowledge broadcast it might be bad for the police,” Barton-Wright noted that skill in the art required regular training and that:

” … this is a club with a committee of gentlemen, among whom are Lord Alwyne Compton, Mr. Herbert Gladstone, and others, and no-one is taught here unless we are satisfied that he is not likely to make bad use of his knowledge.”

This “committee of gentlemen” was a standard convention of Edwardian club-life. Along with Liberal Party politicians Compton and Gladstone, the Bartitsu Club committee included Captain Alfred Hutton, who was also a fencing instructor at the Club, and Hutton’s erstwhile rival Colonel George Malcolm Fox, the former Inspector General of British Army Gymnasia.

Collectively, their role was to act as “guardians at the gate” by assessing the characters of prospective members. Going by the assessments run by comparable clubs, the committee probably interviewed the applicant at some length, asked for letters of reference and ascertained that they were sufficiently solvent to be able to pay their enrollment and tuition fees.

This formal process was especially important because journalists often struggled to imagine why “respectable” people would need or even want to learn the intricacies of Japanese unarmed combat or Professor Vigny’s elegant stick fighting. In introducing the novelty of “recreational martial arts” to London society, Barton-Wright quite frequently had to explain that he was not in the business of training hooligans or “chuckers-out” (Edwardian slang for music hall bouncers).

Inside the Club

While the address at 67b Shaftesbury was fortuitous, in the heart of a busy and popular entertainment district, the very few photographs known to have been taken inside the Club suggest a fairly spartan basement gym.

The ceiling was supported by very sturdy white pillars and dark curtains ran along the white tile walls. The main part of the floor was probably carpet over concrete, with a large matted section for jiujitsu practice.

It’s likely that members would not join expecting the opulence or amenities of older and better-funded institutions, such as the Bath Club. The basement gym was outfitted with “cheval glasses” (large mirrors) and dumbbells among other standard accoutrements of circa 1900 physical culture training. However, Barton-Wright’s elaborate and impressive electrotherapy clinic – which was, arguably, his main business concern – was situated in an adjacent room.

Training

Assuming that the prospect passed the committee’s examination, s/he was then required to undertake an extensive (and expensive) course of private lessons. We have few details as to what these lessons may have involved, but, writing in 1901, Nugent mentioned that “no (group) class-work (was) allowed to be done until the whole of the exercises are perfectly acquired individually”. On that basis, it’s safe to assume that beginners would be drilled in physical culture (calisthenic exercises) and the fundamental skills required in boxing, jiujitsu and cane fighting, all one-on-one with Barton-Wright and the other instructors.

Finally, having passed through an evidently robust battery of character tests and private lessons, fully-fledged Bartitsu Club members could join in the group classes. These seem to have been set up on a kind of circuit-training basis, with students rotating between lessons taught by the various instructors. The most detailed account of regular training at the Club comes from “S.L.B.’s” article in The Sketch of April 12, 1901:

The Bartitsu Club, through its Professors, over whom Mr. Barton-Wright keeps an admonishing eye, guarantees you against all danger. In one corner is M. Vigny, the World’s Champion with the single-stick: the Champion who is the acknowledged master of savate trains his pupils in another. He could kill you and twenty like you if he so desired in the interval between breakfast and lunch – but, as a matter of fact, he never does. He leads you gently on with gloves and single-stick, through the mazes of the arts, until, at last, with your trained eye and supple muscles, no unskilled brute force can put you out, literally or metaphorically.

In another part of the Club are more Champions, this time from far Japan, where self-defence is taken far more seriously than here. The Champion Wrestler of Osaka, or one of the shining lights among the trainers for the Tokio police, dressed in the picturesque garb of his corner of the Far East, will teach you once more of how little you know of the muscles that keep you perpendicular, and of the startling effects of sudden leverage properly applied.

The Japanese Champions are terribly strong and powerful; at a private rehearsal of their work, given some two months ago on the Alhambra stage, I saw a little Jap. who is about five feet nothing in height and eight stone in weight, do just what he liked with a strong North of England wrestler more than six feet high, broad, muscular and confident. The little one ended by putting his opponent gently on his back, and the big one looked as if he did not know how it was done.

There is no form of grip that the Japanese jujitsu work does not meet and foil, and in Japan a policeman learns the jujitsu wrestling as part of his equipment for active service. One of the Club trainers was professionally engaged to teach the police in Japan before he came to England to serve under Mr. Barton-Wright.

When you have mastered the various branches of the work done at the Club, which includes a system of physical drill taught by another Champion, this time from Switzerland, the world is before you, even though a “Hooligan” be behind you.

The Club curriculum also evolved over time. For a period during mid-1901, which was clearly the Bartitsu Club’s heyday, members could also take classes in breathing exercises with Mrs. Kate Behnke. Barton-Wright printed a “remarkable table of results of improvement in breathing capacity and chest girth resulting from respiratory exercises”.

The benefits of membership

Grenfell’s remark about “children and ladies” is telling. All of the Bartitsu Club members for whom we have concrete records were adult men, including a large percentage of soldiers and moneyed athletes. It’s likely, however, that actress Esme Beringer and child actor Charlie Sefton studied historical fencing with Captain Hutton there, and journalist Mary Nugent confirmed that “an endless number” of women did indeed attend classes at the Shaftesbury Avenue Club.

It’s clear that some Club members specialised in certain skills or styles, possibly due to time constraints. Captain F.C. Laing of the 12th Bengal Infantry spent much of his London furlough training at the Club, selecting a combination of jiujitsu and Vigny stick fighting. Laing regretted that he could not prolong his training, but he had to return to his regiment in India when his leave was up.

While Barton-Wright encouraged his employees to train with (and compete against) each other, it’s not clear to what extent the “Bartitsu cross-training” system progressed during the relatively short period the Club was open. It’s very likely that, for example, some of the jointlocks and takedowns recorded in Barton-Wright’s article “Self Defence with a Walking-Stick” were influenced by jiujitsu. The ever-enthusiastic Captain Laing also referred to, but did not detail, combined jiujitsu and stick fighting sequences in his article “The Bartitsu Method of Self Defence”.

Ironically, though, by the time Laing’s article was published, the original Bartitsu Club had closed its doors for the last time …