- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Wednesday, 14th September 2016

This article summarises, and presents some recent research into the origins of the “mixed styles” submission grappling matches that took place in London circa 1900. The term “British jiujitsu” is sometimes used to describe the eclectic blend of jiujitsu styles that were introduced to England (and thus to the Western world) at that time, by pioneers including Bartitsu Club principals Edward William Barton-Wright, Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi.

“Mr. Barton-Wright and his Japanese Wrestlers”

In developing his “New Art of Self Defence”, Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright sought to blend the best of European fighting styles, including boxing and the Vigny method of stick fighting, with Japanese jiujitsu. Barton-Wright himself was among the first Europeans to have studied martial arts in Japan and, in 1900, he invited three Japanese jiujitsuka to London to promulgate their system(s) to a European audience.

Of these men, two were brothers; the younger of them, nineteen year old Yukio Tani, went on to achieve international fame in the jiujitsu vs. wrestling contests pioneered by Barton-Wright, and made London his new home.

Yukio’s elder brother, K. Tani, along with the third man in their group, S. Yamamoto, however, stayed in England for only a few months. They participated in several demonstrations – including Barton-Wright’s famous February, 1901 exhibition for the Japan Society of London – and probably also taught classes at his new Bartitsu Club in Soho, before returning to Japan.

The reason for their departure appears to have been a misunderstanding or disagreement relating to their “duties” as delineated by Barton-Wright, who wanted them take part in open challenge matches in several London music halls. K. Tani and S. Yamamoto refused, citing ethical restrictions against competing as prizefighters. Their decision was explained to bewildered English readers via the sporting and entertainment newspapers as being due to their “high caste” in Japan, but was more likely because K. Tani and Yamamoto believed that competing for prize money in raucous music halls was not a suitably dignified use of jiujitsu.

Shortly after the elder Tani brother and Yamamoto left England, Barton-Wright brought in a fourth Japanese jiujitsuka, the twenty year old Sadakazu Uyenishi. Like Yukio Tani, Uyenishi seems to have had no ethical qualms about professional competition and enjoyed a successful career as a music hall challenge wrestler and jiujitsu instructor in London. Thus, the younger Tani brother and Uyenishi became the first jiujitsuka to travel to the West and compete “against all comers” in professional challenge matches.

K. Tani and S. Yamamoto

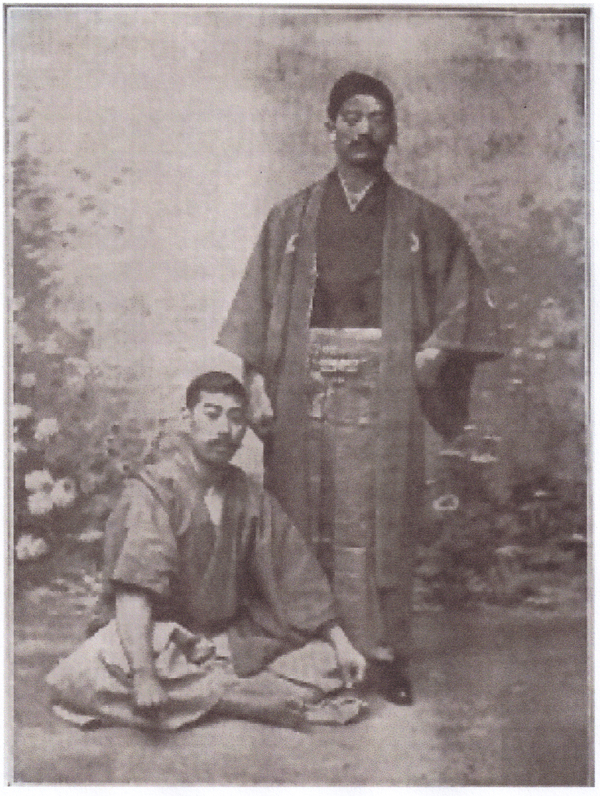

The full names, backgrounds and jiujitsu styles of K. Tani and S. Yamamoto remained unknown until recent research into passport records positively identified the elder Tani brother as Kaneo Tani, the son of sensei Torao Tani of the Tenshin Shin’yo-ryu. Kaneo was born in 1870 and so would have been about thirty years old when he arrived in London; unfortunately, we have no further information about either Kaneo or Torao Tani at present.

Research into the records of the Bugei Ryuha Daijiten (武芸流派大事典), strongly suggest that the Tani brothers’ compatriot was named Seizo Yamamoto. This name is listed alongside those of Tatsugoro Fushimi, Ikeda Tamechi and Eitaro Matsuda as students of the Osaka sensei Yataro Handa. At some point, probably not long before he departed for England, Seizo Yamamoto had also trained in Kodokan judo.

Yamamoto’s fame as an unusually powerful jujitsuka – he weighed around 100 kgs (220 lbs) – was referred to by Mitsuyo Maeda, who had managed to throw the much larger Yamamoto by tsurikomi goshi (“lifting and pulling hip throw”) at a tournament in 1899, shortly before Yamamoto set sail for England. In his book Sekai oko judo musha shugyo,Maeda wrote that he was “very happy to be able to throw such a big man”. In due course Maeda, too, would travel to compete as a challenge wrestler in London, before pioneering Japanese martial arts in Brazil.

Going by these and similar descriptions, it is possible to tentatively identify Seizo Yamamoto as the powerfully built jiujitsuka standing to the right in this photograph from an October, 1901 Sketch magazine article on the Bartitsu Club. Since Seizo had long since returned to Japan by that time, it’s possible that this photograph had taken while he was working at the Bartitsu Club and then simply kept on file until The Sketch had need of a picture of Japanese jiujitsuka.

Yataro Handa and the Handa School in Osaka

Yamamoto’s sensei Yataro Handa was also credited as being Sadakazu Uyenishi’s primary jiujitsu instructor. In a March, 1904 interview with Uyenishi for Health and Strength Magazine, journalist J. St. A. Jewell wrote:

Uyenishi learned the art from Mr. Yataro Handa of Osaka, Japan, whose portrait I have been fortunate enough to secure. This is a feat of which I am proud, for I believe this is the first time Mr. Handa’s portrait has ever appeared in print.

Tani, another famous jiujitsu man, at present appearing on the music hall stage with Apollo, the Scottish Hercules, was also a pupil of Yataro Handa’s, and I believe I am correct in stating that he received the finishing touches of his jujitsu education at Mr. Handa’s hands.

Although Tani’s training with Handa has not been positively confirmed, judo historian Shinichi Oimatsu noted that “Tani was a student of Tanabe Mataemon in Kobe”. Tanabe and Handa were closely associated – more on that later.

The confirmed affiliation of both Uyenishi and Yamamoto with the Handa dojo may have significance to Bartitsu history and to the modern history of submission grappling in the Western world.

That significance is reinforced by the following quote from Taro Miyake, who likewise competed “against all comers” on London music hall stages during the first decade of the 20th century. Miyake, who also opened the London School of Jiujitsu and co-authored (or had ghost-written) the book The Game of Jujitsu with Yukio Tani, was quoted quite extensively on the subject of the Handa school in a 1915 interview with an American reporter:

All, or practically all, of the Japanese jiu-jitsu experts who have exhibited in this country [i.e, the USA] have been exponents of the Kodokan style, which has its headquarters in Tokio. Kodokan jiu-jitsu became popular here because it is the style brought into play when two men are standing and it is spectacular.

Therefore, it was the most suitable method to furnish Americans and Europeans with an illustration of how to repel attacks in ordinary assaults.

The other school of jiu-jitsu is called Handa, and its great teachers are at Osaka, where I learned. Handa is more particularly the kind of jiu-jitsu used when two men are on the mat, as in catch-as-catch-can.

The jiu-jitsu tricks of the tiny Japanese policemen, which have been written about so much by travelers, embody the elementary principles of the Kodokan method, and some of the policemen are quite good at them. As I have said, there is little stand-up work in catch-as-catch-can and Handa experts are the ones to offer a comparison between the Japanese and American methods.

Of course, every Kodokan expert knows more or less about Handa, and every Handa man knows a lot about Kodokan, but nevertheless they are each highly specialized, individual professions. Both have the same fundamental principles applied in all jiu-jitsu, which consists in going against the grain, so to speak. That is, if you grip a man’s arm and can get it out straight, you apply the pressure at the elbow against the direction of the natural crook of that joint, and so on, but each school has its own box of tricks.

Miyake’s remarks should be contextualised as part of the ongoing “style vs. style” hand-to-hand combat controversies that featured in the Western media during the pre-WW1 years. They are, however, also notable in that they conclusively identify the “Handa School” with competitive ne-waza (mat grappling, as in the English catch-as-catch-can style), contrasting that style with the methods of Kodokan judo, which Miyake characterised as standing grappling and throwing or nage-waza.

Allowing that Miyake may well have been communicating with the American journalist via a translator, he clearly meant that he had studied at a jiujitsu dojo in Osaka under a sensei named Handa, but probably did not intend to suggest that the “Handa school” was, in and of itself, a style of jiujitsu.

This is where the history becomes complicated for those who are accustomed to strict correlations between dojo, ryu and sensei.

An entry in the Great Judo Dictionary reports that, in 1881, Professor Jigoro Kano and some Kodokan students had visited Yataro Handa’s Osaka dojo, which was, at that time, listed as being affiliated with the Tenshin Shin’yo-ryu. This was the same style as taught by Yukio and Kaneo Tani’s father, Torao, and was in fact widely practiced throughout Japan during this period. The report notes that, at the time of the Kodokan visit, Handa’s students were not particularly skillful at ne-waza – an apparent reference to their later prowess and fame in that specialty.

The Osaka dojo that Handa opened in 1897, however, seems not to have been affiliated with Tenshin Shin’yo-ryu, but rather a style called Daito-ryu. This was not the well-known style of that name founded by Takeda Sokaku; instead, it was an obscure development of Sekiguchi-ryu jiujitsu.

According to the Bugei Ryuha Daijiten:

Daito-ryu (大東流 ) Jujutsu. One of the offshoots of Sekiguchi–ryu jujutsu. The founder of Daito-ryu is the 9th soke of SekiguchiShinshin-ryu, Sekiguchi Jushin.

Sekiguchi Jushin (関口柔心 )

|

Sekiguchi Hanbei (関口万平 )

|

Handa Yotaro (or Yataro) (半田弥太郎 )

|

Kamimura Yoshio (上村義雄 ) – Fushimi Tokisaburo (伏見良辰三郎 ) – Ikeda Yoshitada (池田為治 ) – Yamamoto Masami (山本精三 ) – Kasuga Nobutaka

Handa’s dojo has attracted some academic interest in recent years, after research by martial arts historians Tony Wolf, Lance Gatling and Joseph Svinth during the mid-2000s identified it as an early centre of innovation in the type of competitive ne-waza (mat grappling) that is now ubiquitous via Brazilian Jiujitsu and Mixed Martial Arts competitions.

Mataemon “Newaza” Tanabe

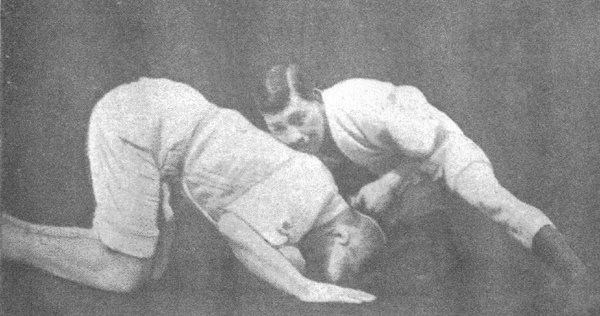

Much of that innovation has been traced to one man – Mataemon Tanabe, who was formally affiliated with the Fusen-ryu but who also developed a personal specialty in/method of competitive submission grappling. As Tanabe recalled in the Dai Nippon Judo-shi:

When I trained with my father’s other students I would never give in to a strangle or a lock. When I was fifteen I got caught in an arm-lock and my elbow was dislocated with a loud crack. My tactic was to wait till my opponent got tired and then make a move to free myself. It was the same with strangles. This ability to endure locks and strangles created various strategies for me. I soon came to be called “Newaza-Tanabe”.

When I was seventeen I participated in a mixed sumo and jujutsu competition which consisted of ten bouts spread over a week. My sumo opponents all weighed about 30kan (248lbs) and I beat them all except for one man called Kandagawa who was so fat I could not get a hold him anywhere.

My jujutsu was not so much the result of my fine teachers (I did learn a lot of wrist releases from my father) but because I always chose to fight strong ones and never give in regardless of injuries or unconsciousness. In this way my jujutsu became polished and this made me work out various ways to capitalize on my strengths. For example, I came up with what I called the Unagi no Osaekata (the eel restraint). As is well known if you press an eel with your hand it will slide away and escape but if you put your hand on it gently it can be trapped. Later I came up with the snake and frog technique. Like the snake that slowly swallows a frog one bit at a time my groundwork overwhelmed my opponents in much the same manner.

Yataro Handa was also the sempai (senior) of Mataemon Tanabe, who went on to be recognised as the 4th soke (grandmaster) of the Fusen-ryu. Thus, it seems likely that, via their sempai-kohai relationship, Handa’s Osaka dojo became an informal headquarters for Tanabe’s innovative and idiosyncratic specialty of submission grappling, as described by himself and by Taro Miyake. Handa and Tanabe may have collaborated on its development over time; ne-waza was not particularly associated with the Fusen-ryu as a formal style, but may have come to define Handa’s Daito-ryu, about which very little is otherwise known. Certainly, by c1900, Handa’s dojo was particularly associated with competitive ne-waza.

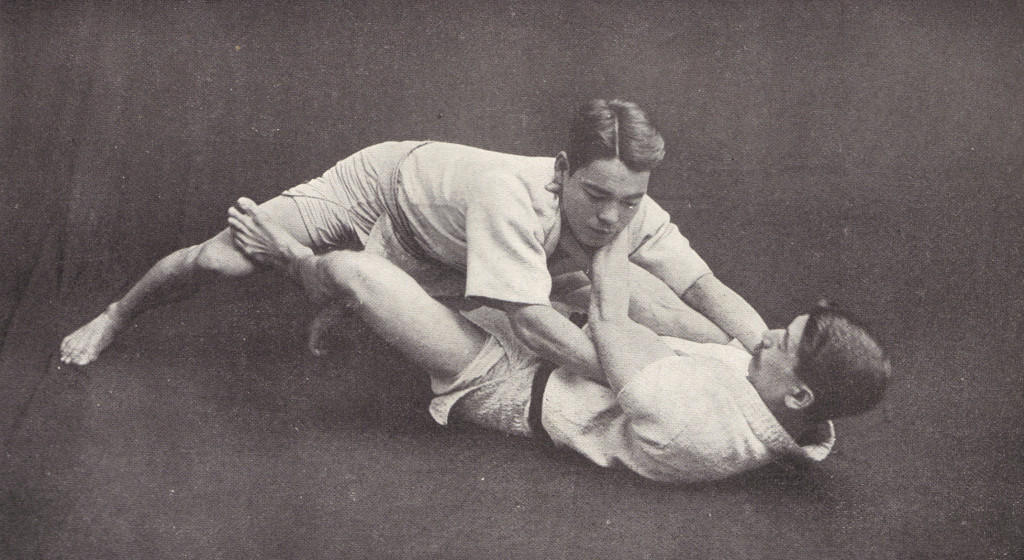

In the first section of this French Pathe film footage, shot in Paris during 1912 , jiujitsu instructors Takizaburo Tobari and Taro Miyake demonstrate a formal sequence of ne-waza techniques. Tobari had begun to focus on ne-waza after losing a sparring match to Mataemon Tanabe in 1891.

According to Japanese martial arts historian Minoru Yamada, Tanabe himself taught both Yukio Tani and Taro Miyake at the Senbukan dojo in Kobe during the 1890s, agreeing with Shinichi Oimatsu’s comment that Tani had been “a student of Tanabe Mataemon in Kobe”. Incidentally – or perhaps not – most of E.W. Barton-Wright’s training was also in Kobe, where he studied at the Shinden Fudo-ryu dojo of sensei Terajima Kuniichiro for about three years (circa 1895-1898).

Thus, and in a sense regardless of their formal ryu affiliations, Yukio Tani, Sadakazu Uyenishi, Seizo Yamamoto and Taro Miyake were all associated with the ne-waza innovations of Mataemon Tanabe and the Handa dojo; Tani via the Senbukan dojo in Kobe and (according to Uyenishi and Oimatsu) via training with Handa; Miyake via both the Senbukan dojo and the Handa dojo in Osaka; Yamamoto and Uyenishi also via training at the Handa dojo.

“Schoolboy jiujitsu”

Bearing in mind that Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi were both very young men when they arrived in London, it’s highly likely that they had honed their competitive ne-waza skills during inter-scholastic shiai (competitive randori or sparring) competitions as teenagers in Japan during the 1890s. A partial list of contests and host schools includes:

1891: No1 High School loses to Gakushuin in judo match

1898: Judo match between No1 and No2 High Schools

1899: No1 against No2

1901: No3 against Kanazawa Medical school

1902: No3 against Keio University

1906: No1 against Tokyo Teachers school

1907: No4 against No6

1908: No6 against Kobe High School of Commerce

1909: No3 against No6

1910: No5 against No7

1910: No1 against No2

Inter-scholastic competition rules (or informal conventions) emphasised ne-waza, due to the belief that mat-grappling was safer than high-amplitude throwing for young competitors and helped to “level the playing field” between styles and competitors. Those rules also, inevitably, fostered an environment of technical experimentation, as young practitioners from various styles met in competition for the first time.

It’s likely that Handa dojo trainees would have done particularly well in these semi-formal contests, and tempting to speculate that the dojo, and Tanabe’s ne-waza methods, might have served as laboratories for the competitive submission grappling skills that emerged from the stylistic melting pot of inter-scholastic shiai. Indeed, Tani, Miyake and Uyenishi all claimed various championships when they travelled to England.

In 1914 the “schoolboy jiujitsu” contests were formalised and sanctioned under the Kodokan judo banner by Professor Jigoro Kano.

“There is so large an element of trickiness about the Japanese method that the English expert might well be caught unawares …”

When Tani and Uyenishi first began to compete in London music halls, numerous journalists and other observers marvelled at the jiujitsukas’ expertise at submission wrestling. This was a great (and frequently controversial) novelty in comparison to the traditional, fall- or pin-based European wrestling styles of their day. Some critics complained that the Japanese style seemed to be made up of “absolute fouls”, but others remarked that, as unorthodox as the notion of grappling for submission holds may have been to English sensibilities, it was undoubtably effective and well-suited for training in self-defence.

Because Edward Barton-Wright framed his “all comers” challenge matches as “tests” of jiujitsu against European wrestling styles, the matches were effectively fought under competitive jiujitsu rules, regardless of the preferred style(s) of the wrestlers. Challenged to win prize money by avoiding being submitted within a particular time period, a champion in the Cumberland/Westmoreland style, for example, might find that he was able to throw one of the Bartitsu Club jiujitsuka, but was at a loss as to what do when the jiujitsuka continued to fight after the fall. Likewise, a catch-as-catch-can wrestler might be able to pin a jiujitsuka’s shoulders to the mat, only to then find himself caught in a submission lock.

With their typically much larger opponents being inexperienced in submission grappling and required to wear jiujitsu gi jackets, Tani and Uyenishi made quick work of most of their matches. As they were joined in London by Taro Miyake, Akitaro Ono, Mitsuyo Maeda and other venturesome Japanese combat athletes, their collective successes in numerous challenge contests during the first decade of the 20th century swiftly established the efficacy of jiujitsu.

So it was that the competitive submission wrestling spread from the music hall stages of Edwardian London, as European wrestlers grappled with – and learned from – jiujitsuka trained in the Tanabe/Handa methods.