- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Sunday, 18th March 2018

The following article by N. Tegan Lewis was originally published in the Women’s Freedom League newspaper of April 22, 1909, following the jiujitsu self-defence displays by Edith Garrud at London’s Caxton Hall (shown above).

We’ve offered a few contextual annotations, which are shown in italics.

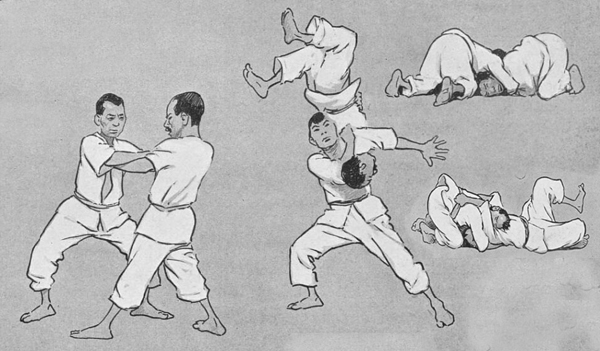

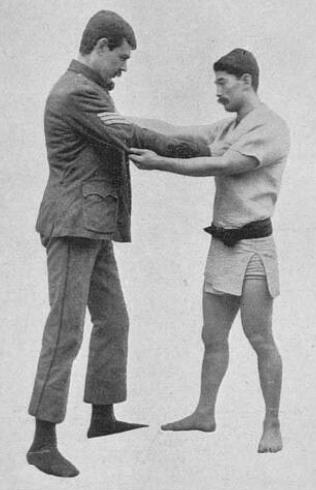

A novel feature of the Green, White and Gold Fair, at Caxton Hall, was the jiu-jitsu displays given by women. Apart from the fact that it is splendid physical exercise, jiu-jitsu is the most suitable form of self-defence for women, success depending on the dexterous use of the opponent’s strength. The science has three branches: the throws, which require much practice; the art of self-defence exclusively, by which all attacks by violence may be resisted; and the art, when the opponent has been thrown, of wrestling on the ground and rendering him unconscious by neck locks and other means. Happily, measures so stringent as those taught in this third branch are not often necessary, but in an encounter with a desperate burglar or an escaped lunatic the knowledge would be decidedly useful.

Emily Watts, another pioneering jiujitsu instructor of this era, largely dismissed ne-waza (mat grappling) in her 1906 manual The Fine Art of Jujutsu, on grounds of sensibility rather than practicality.

In the course of the last quarter of a century women in this country have developed physically, as mentally, in an amazing way while men have been—well, let us say—at a standstill. The modern healthy girl, backed by a knowledge of some scientific art of defence, could render a very good account of herself when necessary and men “Anti’s” who are so fond of the physical force “argument” would do well to take heed in time lest the day come, and perhaps it is not far distant, when they will not be allowed to let the matter drop.

“Anti’s” refers to those who were against the movement towards women’s suffrage. The fallacious “argument of physical force” essentially stated that women should not be given political power on the grounds that such power ultimately resolves into the ability to exert physical force.

We are all familiar with Mr. Punch’s famous advice to those about to marry, but, though Mr. Punch “were like to die of it,” we have not yet heard Mrs. Punch’s opinion on the matter. May we suggest, with all due deference to Mr. Punch, that her advice to the girl would be “learn jiu-jitsu”?

During the Edwardian period, the Punch and Judy puppet show preserved Mr. Punch’s ferocious violence against virtually all the other characters, including his wife Judy.

Such a precaution would be, let us hope in the majority of cases, merely a matter of form. At the same time it is idle to ignore the fact that there are men, in all classes of society, who habitually ill-treat their wives. At present the usual advice given to the ill-used wife, when circumstances render it practically impossible for her to leave her husband, is “do not lower yourself by retaliation, at all costs uphold your womanly dignity.” Setting aside the utter impossibility of being dignified under such circumstances this advice is, theoretically, perfectly sound. Practically jiu-jitsu is likely to prove far more effective for it is universally acknowledged that your bully is usually a coward.

The theme of jiujitsu as self-defence against an abusive husband provided the basis of the polemic playlet What Every Woman Ought to Know (1911), which included a spectacular fight scene staged by Edith Garrud.

It has long been the custom to consider women more timid than men, but one has only to scan the newspapers day by day to realize that in cases of great emergency—such as the Messina earthquake—women are every whit as brave as men; and hardly a week goes by but some woman goes to the assistance of the police in a street brawl while a crowd of men—citizens stand idly by, indifferent or amused, oblivious of any responsibility. Moreover, in the days when entrance to the army was an easy affair, many women fought side by side with the men and many instances are on record of women taking part in sea fights. There was Hannah Snell, who enlisted as a marine and saw active service, and Mary Ann Talbot, otherwise John Taylor, who was wounded in the action of the Glorious First of June, both of whom received pensions from a grateful Government. Anne Bonney and Mary Read, after serving in the Navy, turned pirates—to their own profit, doubtless, if not to that of the State.

Public opinion has hitherto been the greatest enemy to the physical development of women; the pioneer women cyclists were covered with scorn, the girls who first declared their preference for hockey over croquet were looked at askance as hoydens. Happily the world soon gets accustomed to new ideas, and to-day the girl who cycles and the girl who plays hockey are taken very much as a matter of course—just as will be the girl of to-morrow who practises jiu-jitsu. In a few years time let us hope that the woman who is not versed in the art of self-defence will be regarded, and rightly regarded, as an anomaly.

Edith Garrud’s demonstrations did, in fact, spark a wide interest in women’s jiujitsu, including a fad for “jiujitsu parties”. Mrs. Garrud also established an exclusive “Suffragettes Self-Defence Club” and, several years thereafter, became the jiujitsu instructor for the secret Bodyguard Society of the Women’s Social and Political Union.