- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 31st January 2019

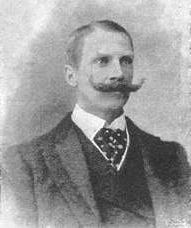

The following interview with Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright first appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette of 5 September 1901, during the height of the Bartitsu Club era. It was found and republished by the Bartitsu Society in October of 2011 and subsequently inspired several new insights into the tactics of Bartitsu as a practical martial art.

This post re-examines the interview in light of more recent discoveries, with added notes (in italics) for context and clarity.

BARTITSU: ITS EXPONENT INTERVIEWED

One of our contributors lately called on Mr. Barton-Wright in his well-appointed gymnasium in Shaftesbury Avenue, when the following conversation took place:

What is the word Bartitsu? – It is a compound word, made up of parts of my own name, and of the Japanese Ju-jitsu, which means fighting to the last.

What do you claim for your system? – It teaches a man to defend himself effectively without firearms or any other weapons than a stick or umbrella, against the attack of another, perhaps much stronger or heavier than himself.

How does it differ from the usual fencing or boxing? – The fencing and boxing generally taught in schools-of-arms is too academic. Although it trains the eye to a certain extent, it is of little use except as a game played with persons who will observe the rules. Most of the hits in (single)stick or sabre play are taken up by the hilt, which a man is not very likely to take out with him on his walks.

This was a frequent theme of Barton-Wright’s (and, implicitly, of Pierre Vigny’s), and refers to the exclusion, within Vigny’s stick fighting system, of parries in the orthodox fencing-based guards of tierce and quarte. The Vigny system was virtually unique for its time in defaulting to high or “hanging” guards, in which the defender’s stick-wielding hand is always positioned above the point of impact between the two weapons.

Barton-Wright’s pointed comment about recreational fencing and boxing being “too academic” was significant especially with regards to the ongoing “practicality vs. artistry” arguments in French martial arts circles circa 1900.

The head, too, which is a part which an assailant who means business would naturally go for, is so well protected that the learner gets careless of exposing it.

And the boxing? – The same objection. The amateur is seldom taught how to hit really hard, which is what you must do in a row.

Pierre Vigny also addressed this point, in some detail, in a rare October 1900 letter published in the French journal La Constitutionelle. In contrast to the extravagantly polite, academic style that was then being successfully promoted by Vigny’s rivals Charles and Joseph Charlemont, the style of kickboxing taught by Vigny at the Bartitsu Club was closer to the continuous, full-contact model of English and American boxing.

Nor is he protected against the savate, which would certainly be used on him by foreign ruffians, or the cowardly kicks often given by the English Hooligan.

A little knowledge of boxing is really rather a disadvantage to (the defender) if his assailant happens to be skilled at it, because (the assailant) will know exactly how his victim is likely to hit and guard.

Barton-Wright here alludes to the so-called “secret style of boxing” which appears to have been a collaboration between himself and Vigny; more to follow on that subject.

And you can teach any one to protect himself against all this? – Certainly. The walking-stick play we will show you directly. As to boxing, we have guards which are not at all like the guards taught in schools, and which will make the assailant hurt his own hand and arm very seriously.

So we teach a savate not at all like the French savate, but much more deadly, and which, if properly used, will smash the opponent’s ankle or even his ribs.

Aside from hitting harder than would normally be tolerated in recreational boxing, “Bartitsu (kick)boxing” – with its emphasis on actual unarmed combat, rather than sport and exercise – notably included, as Barton-Wright discussed elsewhere, guards “done in a slightly different style from boxing, being much more numerous as well”. This interview clarifies that these guards served the specific tactical purpose of damaging the opponent’s attacking limbs en route to the unarmed defender entering to close quarters.

Even if it be not used, it is very useful in teaching the pupil to keep his feet, which are almost as important in a scrimmage as his head.

Anything else? – My own experience is that the biggest man in a fight generally tries to close. By the grips or clutches I can teach, the biggest man can be seized and made powerless in a few seconds.

Barton-Wright evidently considered jiujitsu to be something of a “secret weapon” – an entirely valid point of view at this time, because his Bartitsu School of Arms was literally the only place outside of Japan where English students could learn the “art of yielding”. Jiujitsu was presented as the “endgame” in all of the various tactical unarmed combat scenarios proposed by Barton-Wright during this period.

If you sow this knowledge broadcast it might be bad for the police.– Yes; but it cannot be picked up without a regular course of instruction, or merely by seeing the tricks. Moreover, this is a club with a committee of gentlemen, among whom are Lord Alwyne Compton, Mr. Herbert Gladstone, and others, and no-one is taught here unless we are satisfied that he is not likely to make bad use of his knowledge.

Previous commentaries upon Bartitsu from outside observers, including some journalists, had questioned whether the art had any real application other than by “chuckers-out” (Edwardian slang for nightclub bouncers). The Pall Mall Gazette interviewer was not the first to worry about what might happen if “hooligans” were to learn the art, though still other commentators imagined scenarios in which Bartitsu Club members might patrol “hooligan infested” areas of London to exercise their proficiency.

This skepticism over motivations raises the important point that Bartitsu was an extreme novelty in its time and place; a method of recreational antagonistics that was nevertheless practiced primarily to prepare the student for self-defence, with sporting and exercise benefits being of secondary concern. Vetting by the Bartitsu Club’s “committee of gentlemen” was, thus, a necessary step towards establishing social respectability.

It must have taken you some time to work out all this? – Yes, but it was in great measure a matter of necessity. As a mining engineer in all parts of the world, I have often had to deal with very unscrupulous fighters, and, being a light man, I had to protect myself with something else than my fists.

In March of 1902, a report on a Bartitsu Club exhibition at Oxford University included the following anecdote about Barton-Wright’s perilous travels abroad; “He had frequently been attacked abroad, where they did not believe in our methods of fair play and would injure a man with a bottle, knife, chair, or any weapon which came to hand, and it was very useful to know how to prevent a man from using a knife upon one, though he might not stab one very deeply, yet there was danger of bleeding to death in some lonely place before help could be brought.

He had been attacked with picks, crowbars, scythes, spades, and various other weapons, and, as quick as he was in boxing, he was obliged to close with his man, and had he not known anything of wrestling, he would have been overpowered many times. As a means of meeting emergencies of that kind, he recommended (this) form of self-defence.”

The tactic of closing in to grappling range against opponents armed with more powerful weapons might well have influenced Barton-Wright’s collaborations with Pierre Vigny vis-a-vis Bartitsu stick fighting.

Mr. Barton-Wright then gave our contributor a demonstration of his method. His fencing-master, M. Pierre Vigny, stripped to the waist and without any other weapon than an ordinary walking-stick, will allow you to attack him with singlestick, sabre, knife or any other short weapon without your being able to touch him, he taking all blows on what fencers call the forte of his stick. He will at the same time reply on your head, and knuckles; while, if he is given a stick with the ordinary crook handle, he will catch you by the arm, leg or back of the neck, inflicting in nearly every case a nasty fall.

He has also a guard in boxing on which you will hurt your own arm without getting within his distance, while he can kick you on the chin, in the wind, or on the ankle. As to the usual brutal kick of the London rough, his guard for it (not difficult to learn) will cause the rough to break his own leg, and the harder he kicks the worse it will be for him.

Again, emphasis is given to the destructive blocks of the “secret style of boxing” practiced at the Bartitsu Club.

Mr. Barton-Wright himself shows you wrestling tricks, by which, by merely taking hold of a man’s hand, you have him at your mercy, and can throw him on the ground or lead him about as you wish, the principle being, apparently, that you set your muscles and joints against your opponent’s in such a way that the more he struggles, the more he hurts himself.

This is one of the comparatively few concrete references to Edward Barton-Wright actually teaching at the Bartitsu Club.

A couple decidedly bad to beat.