- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 14th March 2019

The “last hurrah” of the venerable English tradition of quarterstaff fighting took place on the gladiatorial stages of the early 18th century, when professional roughhousers such as James Figg “took on all comers” with various weapons for the chance to win prize money. As the sport of boxing overtook weaponed stage-fighting, the quarterstaff largely receded into folklore, aside from sporadic and largely undocumented revivals via rural fairs.

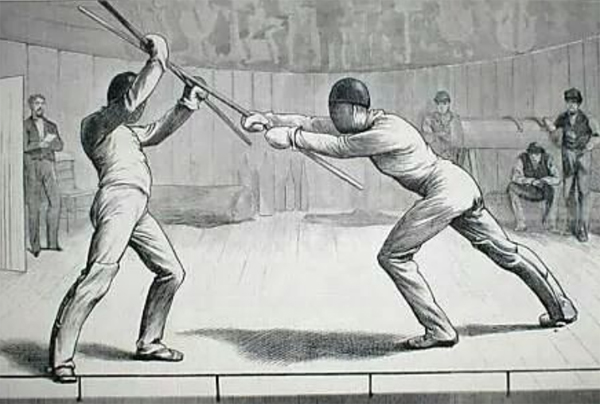

During the mid-late 19th century, however, the confluence of newly-devised protective equipment for sports such as cricket and fencing and the renewed enthusiasm for the tales of Robin Hood laid the basis for a widespread quarterstaff fencing renaissance.

From the 1870s onwards, the old/new sport became particularly popular among soldiers and was frequently a highlight of “assault-at-arms” exhibitions, featuring displays of martial gymnastics and all manner of antagonistics. Two instructional manuals were produced – Thomas McCarthy’s Quarterstaff: A Practical Manual (1883) and a chapter in R.G. Allanson-Winn’s comprehensive Broadsword and Singlestick (1898).

Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright claimed that he had often had to defend himself against attackers armed with quarterstaves – among an alarming variety of other weapons – during his travels abroad. It’s likely that he was referring to his time working in mining settlements in Portugal, where the folk-sport/martial art of jogo do pau was widely practiced during the late 19th century, though the matter of why he may have been repeatedly attacked there remains open to speculation. In any case, according to Barton-Wright’s own reports, his favoured tactic of closing in against opponents armed with superior weapons – notably a feature of his presentations of the Vigny method of stick fighting – was inspired by these encounters.

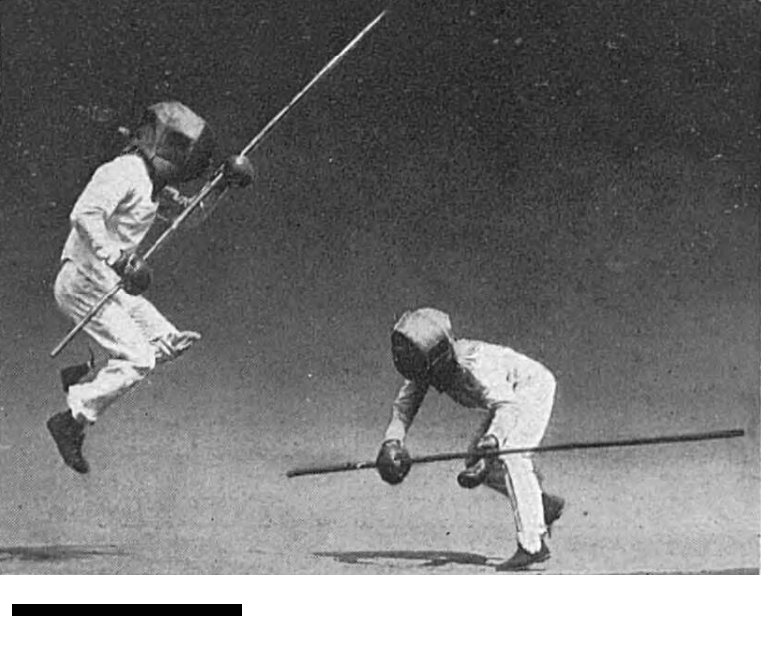

In England, quarterstaff fencing exhibitions persisted well into the 20th century, sometimes incorporating crowd-pleasing “stunt” elements, which had been disparaged by Thomas McCarthy as “made-up affairs, just for show”. Interestingly, a number of late-19th century reports on quarterstaff matches refer to disarmed combatants immediately shifting to boxing – though it’s difficult to say to what extent this may also have been tongue-in-cheek showmanship for the crowd.

This rare snippet of film from a 1925 military display in Portsmouth features a moment from a particularly “showy” bout with staves, reminiscent of professional wrestling:

“Look, what’s that up there?!” An old trick given a new twist.

The Boy Scouts also took to quarterstaff fencing and, for a brief period, it was listed alongside singlestick play, boxing, foil fencing, wrestling and even jiujitsu as accomplishments required to achieve the Master-at-Arms badge. The Scouts also produced their own, simplified manuals for the instruction of young staff fencers.

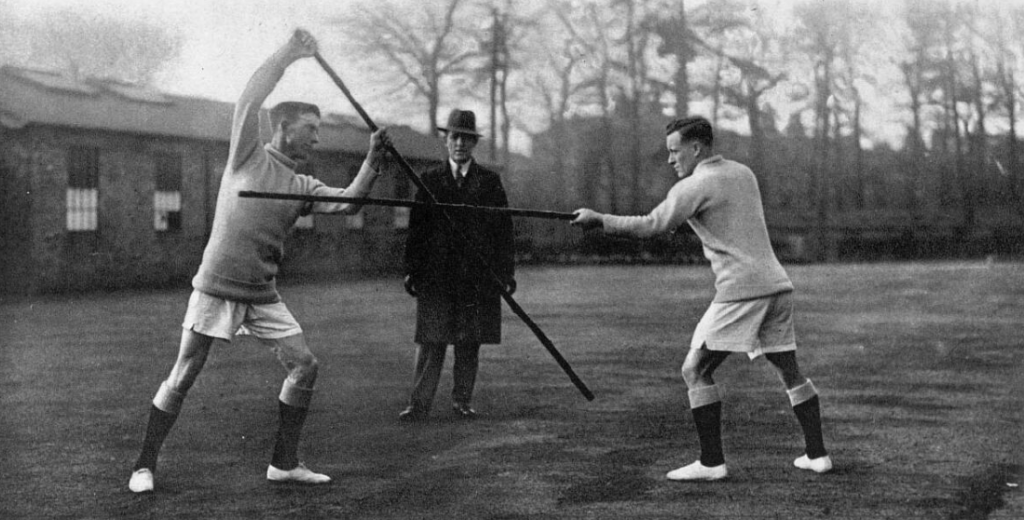

The following, newly-discovered pictures represent a fairly late addition to the corpus of English quarterstaff fencing materials. They originally appeared in an Illustrated London News article titled “The Quarterstaff: Then and Now”(1934). The photos were taken at the Royal Air Force Depot in Oxbridge, and feature R.A.F. swordsmen Sergeant Turner and Sergeant Jarrold, “refereed” by Professor Ware. Note that, although Turner and Jarrold are shown here in regular gym kit for purposes of demonstration, during competitive staff play they would have worn protective equipment of the type shown above. The captions are by M. Pollock Smith.