- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 7th March 2019

The author of this short critical article, first published in the Sheffield Evening Telegraph of 28 August 1901, jumps to several mistaken conclusions about Bartitsu, jiujitsu and Japanese wrestling as a general subject, which are addressed below in italics.

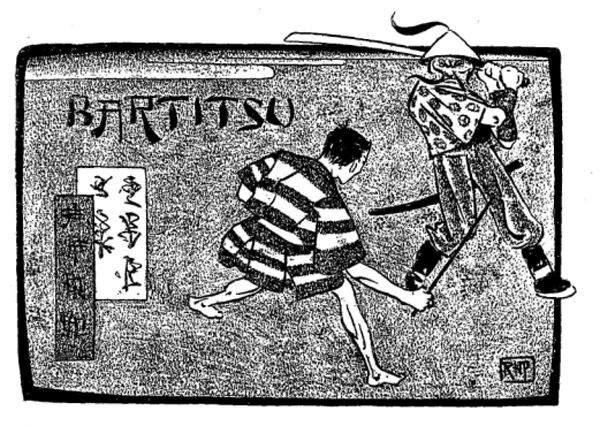

We are hearing so much just now of Mr. Barton-Wright’s introduction into England of what he calls in bastard Japanese “bartitsu,” or the ideal art self-defence, that it is not impertinent to inquire, says the “Daily Chronicle,” why we have never heard of it before.

The answer is that, despite Edward Barton-Wright’s persistant efforts in explaining that “Bartitsu” was the name of his own, new art of self-defence, combining Japanese wrestling with the Vigny cane system and with European boxing, etc., spectators and reviewers frequently missed the fact that Bartitsu included jiujitsu, instead mistakenly assuming that Bartitsu was the name of the Japanese style.

Mr. Wright says that the Japanese hold this secret art of theirs in such reverence that it has never yet been allowed to shown publicly their own land, much less abroad, and we are bound to believe him even though this semi-sacred cult is first revealed to the British public by its native exponents upon a music hall stage.

Barton-Wright himself had exhibited jiujitsu publicly on several occasions prior to the first London music hall displays. Otherwise, he was correct in stating that it had never before been formally exhibited in Europe, apart from a one-off lecture and demonstration by the Japanese banker/jiujitsu enthusiast Tetsuro Shidachi at the inaugural meeting of the Japan London Society.

Although certainly not a “secret art”, jiujitsu was rarely exhibited in Japan during the 1890s and very early 1900s. This was due less to any “semi-sacred cult” status and more to the fact that it was widely regarded as being an obsolete relic of the Edo Period (1603-1868) until Dr. Jigoro Kano’s development and promotion of Kodokan judo, which was still a work in progress during Barton-Wright’s time in Japan.

Tbe system is undoubtedly effective, just as effective indeed as that of the “hooligan,” who, disregarding all recognised rules of offence and defence, hits his opponent where and when he can.

Similar observations about Japanese unarmed combat being comprised of “absolute fouls“, etc., were frequently made by English observers during this period, sometimes as the basis for objections against mixed jiujitsu vs. wrestling contests. Most observers, however, respected Barton-Wright’s point that his music hall exhibitions were intended to illustrate the effect of jiujitsu as an art of self-defence.

The amazing part of it is that, though wrestling has been a sport in Japan for more years than can well be counted, the art of “bartitsu” has never been imported into it. Mr. Wright explained this by saying, first, that the art was a secret one. It was only known among the highest classes; secondly, that for its effective performance grip on some the clothes was necessary, whereas, of course, Japanese wrestlers when they appear the ring are almost nude. These, no doubt, are excellent reasons, but one cannot help thinking that if “bartitsu” is all pretends to be, then even a naked body would offer some holds to an experienced exponent.

The Japanese wrestler, moreover, belongs to a distinct class, and what he does not know about wrestling in an orthodox or even unorthodox way can scarcely worth the knowing.

Here the journalist alludes to sumo wrestling, but overreaches by failing to recognise the fundamental difference between sport and self-defence. Sumo wrestlers did, in fact, employ all manner of jiujitsu-like throws that were advantageous within the rules and conditions of their sport, which automatically discounted all throws in which the thrower fell to the ground before his opponent – an action that would count as a loss on behalf of the first man down – not to mention the gamut of jiujitsu techniques that require gripping the opponent’s jacket. Similarly, numerous jiujitsu techniques such as extended jointlocks, most atemi-waza (striking techniques) and all newaza (mat grappling techniques) were either illegal in, or irrelevant to sumo wrestling, due to safety concerns and to the stylised conventions of winning a sumo contest.