- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Saturday, 3rd September 2011

Dutch journalist Erik Noomen’s well-researched article on the history and revival of Bartitsu has been featured in the Volkskrant, one of Holland’s largest daily newspapers. Touching on Bartitsu’s connection with the Steampunk subculture and the Sherlock Holmes mythos and featuring comments by Dutch Bartitsu instructor John Jozen, Mr. Noomen’s article is an excellent introduction to the subject for Dutch readers.

An English translation of the article is now available here:

Everyone thought that ‘baritsu’, the magical martial art of Sherlock Holmes, was a figment of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s imagination. Until, suddenly, yellowed articles showing moustachioed martial artists were found under a century of dust. Now the first ‘mixed martial art’ is the subject of international attention.

Fans of the Sherlock Holmes stories know that the Master Detective threw Professor Moriarty from a rocky precipice with his knowledge of “baritsu”. In the story The Adventure of the Empty House, baritsu is described as being a form of Japanese wrestling; the word appears nowhere else. Many readers thought, therefore, that the fighting style was invented by the author, Arthur Conan Doyle.

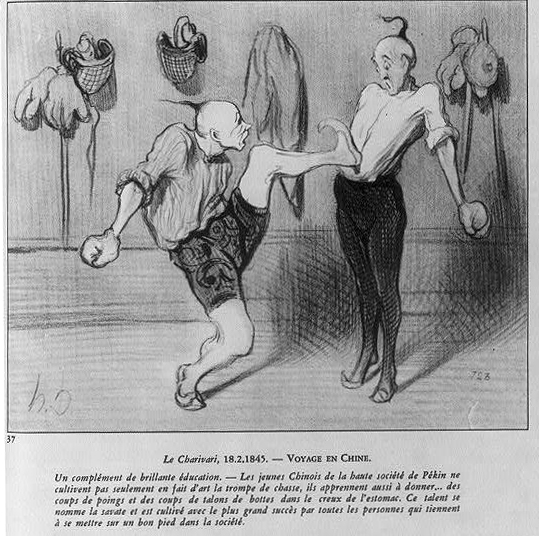

Just over ten years ago two English researchers proved the contrary, when they found hundred-year-old articles with sketches and photographs of jacketed Englishmen with straw boater hats and handlebar moustaches, fighting each other with bare fists, umbrellas and vicious whipping canes.

Doyle’s “baritsu” was actually called “Bartitsu” and was developed by Edward William Barton-Wright, an eccentric engineer who had learned various martial arts during his travels throughout and beyond the British Empire. Returning home to London after having lived for three years in Japan, he decided to combine his knowledge of Jiu-Jitsu with English boxing, wrestling and the Swiss/French la canne, in which the cane was used to hold malodorous Apaches (Parisian street thugs) at bay. The result was the world’s first mixed martial art combining Asian and European fighting styles. With no undue humility, in 1898 the Brit coined the term “Bartitsu”: a contraction of Barton-Wright and jiu-jitsu.

The new trend lasted only four years, then jiu-jitsu took the torch and Bartitsu disappeared rapidly into oblivion. However, that time is over. Since 2009, you may even speak of a modest craze, thanks to the Sherlock Holmes film, starring Robert Downey Jr., which managed to make a street fighter out of the cerebral Victorian sleuth, armed against the dregs of the London underworld with decisive punches and Barton-Wright’s stick tricks.

In 2006 there was only one school that frequently regularly offered Bartitsu lessons. In the year 2011, over twenty clubs and courses are devoted to the sport. At “Steampunk” conventions (where 19th-century machines and fashions are mixed with a modern sensibility), Bartitsu demonstrations are given in late-19th century clothing.

The Netherlands remains a little behind the trend: a total of six of our countrymen practice Bartitsu. And that includes instructor John Jozen of the Shizen Hontai martial arts association in Veldhoven, the only place in the Netherlands where, every week, Bartitsu-style self defence with a walking stick is practiced. Jozen: “Bartitsu is not very practical if someone is threatening you with a gun. You’d do just as well throwing a ball to distract him as waving a walking stick or throwing a coat over his head.”

At the basis of this Bartitsu revival is Tony Wolf, the “Cultural Fighting Styles Designer” who trained the orcs and elves to fight for the Lord of the Rings movies. In 2005 he started organising Bartitsu reconstructions, using self-made rattan canes with a steel ball handles. The Holmes film and the stylish BBC-TV series last year, which sees Holmes solve his cases in modern London, have made Bartitsu cool again, says Wolf.

Both projects will have sequels later this year. As seen the trailer for the movie Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, the film will show lots of “Bartitsu-style” punch-ups.

The steady renaissance of Bartitsu during the 21st century stands in stark contrast to the explosive growth of the sport during the late 19th century. Shortly after his return to London, Barton-Wright presented self-defence demonstrations in men’s clubs and for charitable benefits, with great success. Jozen: “Between 1880 and 1920, carrying weapons such as swords in cities was forbidden, hence gentlemen switched en masse to sturdy walking sticks. Not only as fasionable accessories, but for fear of infamous street gangs such as the “Hooligans” in London and the “Apaches” of Montmartre, stories about whom filled the newspapers of the day.” An additional benefit of the cane as a weapon was that, as Barton-Wright said, it was possible to defeat scoundrels “without getting one’s hands dirty”.

In 1899 his company opened the London Bartitsu Club: “a huge underground hall with gleaming white tiles and electric light, with champions stalking around like tigers”, according to an excited journalist in 1901. Most members were soldiers, athletes, actors, politicians and aristocrats. The teachers that Barton-Wright had brought to London were also impressive. From Japan came the jiu-jitsu legend Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi, from Switzerland, the heavyweight wrestler Armand Cherpillod and the famous master-at-arms Pierre Vigny, an expert in savate (French kickboxing) and inventor of the remarkable cane fighting.

Although Bartitsu was subtitled the “gentlemanly art of self defence”, not all its practitioners were real gentlemen. Among the soldiers, athletes, actors, politicians and aristocrats who joined Barton-Wright, for example, was Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon. This Olympic fencer would later acquire infamy as one of the few male passengers to survive the sinking of the Titanic, allegedly because he had bribed sailors in his lifeboat not to rescue others in the water (E.N. – Duff-Gordon was later cleared of these charges after an extensive inquiry).

Women also practiced Bartitsu. Feminist Edith Garrud later started her own dojo, which was used as a refuge for the “suffragettes”, revolutionary fighters for women’s voting rights. It was also there that they trained “The Bodyguard”, a secret society of women that physically protected speakers at their meeting against attacks by conservative Londoners. Their jolly nickname: the “Jiu-jitsuffragettes”.

Training at the Bartitsu Club must have offered a spectacular sight. Articles of the period reveal how you can prevail if armed only with your umbrella, or even while riding a bicycle. Photographs show a prosperous lady in a long dress with a huge, flowery hat riding primly on a country lane. She is pursued by a villain, also riding a bike, whom she defeats by suddenly braking, causing him to crash to the ground. In the next picture you see her pedalling away and waving back with an affable smile.

In 2011, however, John Jozen parks his bike every Saturday just outside the dojo in Veldhoven. He limits his Bartitsu training to walking sticks or umbrellas. “Although I must admit my wife is not happy that I have now beaten four or five umbrellas to shreds. Therefore I now buy old canes in charity shops, and sometimes even bamboo canes from the hardware store. These don’t cost so much.”

Barton-Wright was not so frugal. Three years after its establishment, he had to close the Bartitsu Club. Arguments with his famous jiu-jitsu teacher and the small number of Londoners willing or able to pay the extensive fees, made him decide in 1902 to seek his fortune in electric health equipment. This, too, was a mixed success. The ultraviolet lamps and heat rays which he imported were perhaps beneficial, but other inventions such as the Nagelschmidt Apparatus (an electric chair intended to stimulate muscle growth and reduce fat) sometimes made rheumatic patients go from bad to worse.

Barton-Wright died in 1951, almost penniless and forgotten, and was buried in an anonymous “pauper’s grave”.

Today, the sport of mixed martial arts is a billion-dollar industry. Fights promoted by the Ultimate Fighting Championship are watched by tens of millions of fans via pay-per-view and MMA fighters like Anderson Silva, Georges St. Pierre and Matt Hughes earn big money every year.

One would hope that modern fighters would respect the legacy of eclectic martial arts training from yesteryear, but this is not always the case. When John Jozen shows them historic photos of fighters in the Bartitsu Club, their responses are often rather condescending. Jozen: “They ask if you can tell what degree the Bartitsu fighter has gained by the size of his moustache, or whether he wears suspenders.” He must laugh himself. Jozen quickly stresses quickly that he and his students usually practice in modern sportswear, not quaint 1900s-style leotards.