- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Sunday, 2nd October 2016

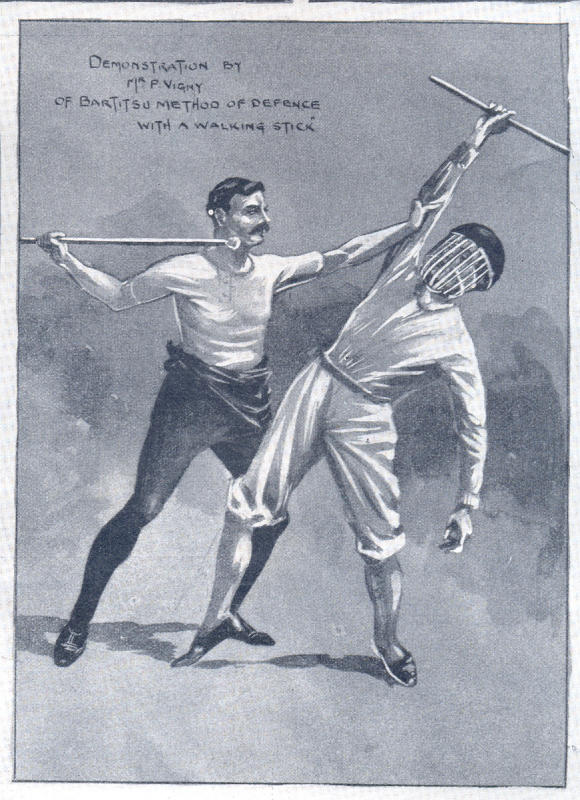

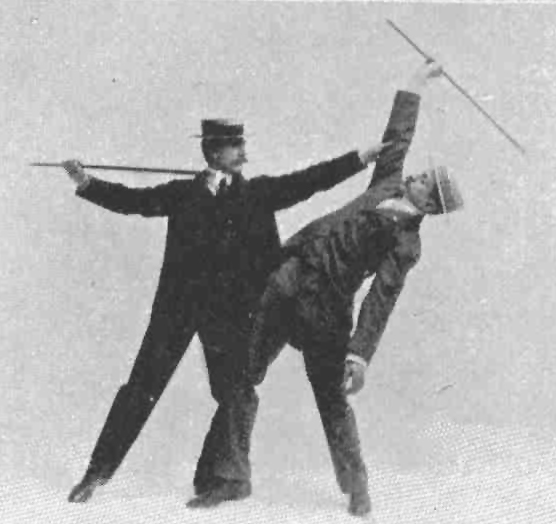

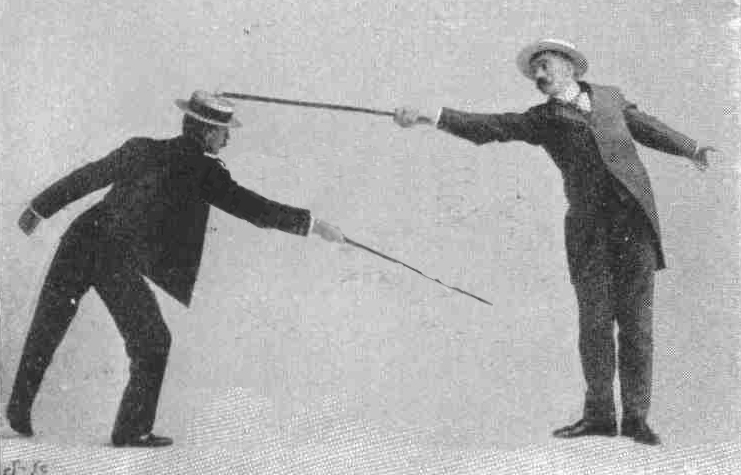

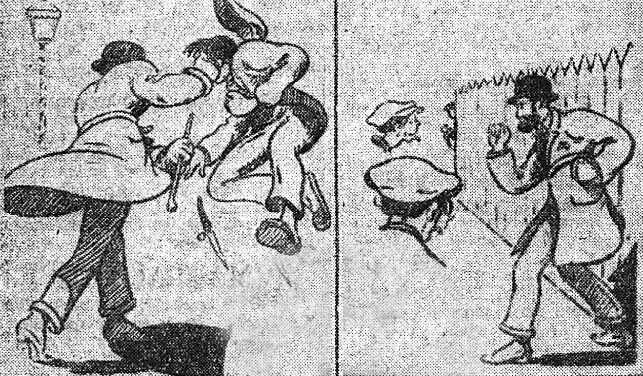

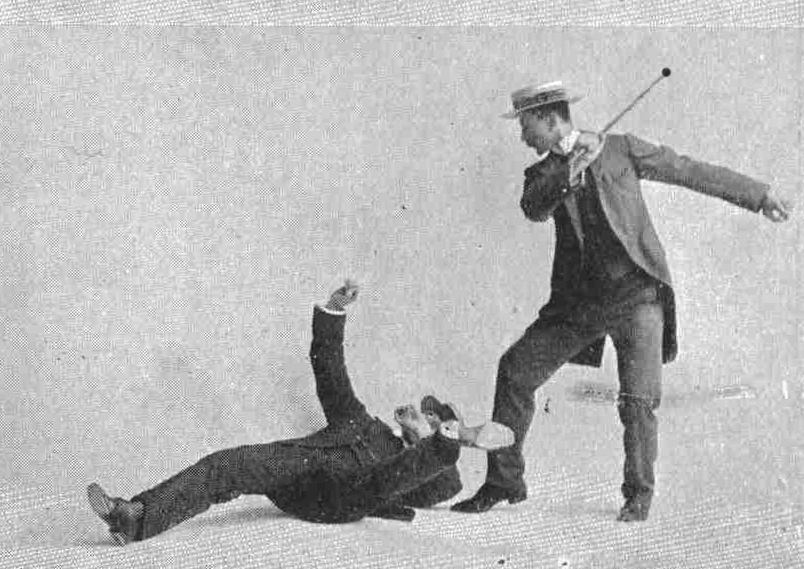

Above – the active use of the free hand in several canonical Bartitsu set-plays.

Going by all historical evidence, the transition from cane-fighting distance to close-quarters combat was one of the defining characteristics of Vigny stick fighting as it was taught at the original Bartitsu Club. Of the 22 set-plays demonstrated in Edward Barton-Wright’s 1901 article series Self-Defence with a Walking Stick, over half involve some form of trap, “seizure” or open-hand press, leading into a counter-strike and/or a throw or takedown.

Clearly, this emphasis upon the active use of the “free hand” – i.e., the non-weapon-wielding hand – was a notable distinction between Bartitsu stick defence and the more orthodox systems of stick fighting commonly practiced during the late 19th century, which typically treated the stick as if it were a substitute sabre. Likewise, the Vigny style’s use of ambidextrous attack and defence from deceptive two-handed guards was much remarked upon by observers, and of course Vigny’s eschewing of fencing-style guards and parries in the third and fourth positions in favour of a dynamic range of both high and low guards was a radical departure from the tactical norm.

Here follow a selection of close-combat traps, seizing and pressing techniques drawn from Barton-Wright’s articles:

Above: Pierre Vigny (right) seizes Barton-Wright’s weapon hand and prepares a scissoring stick takedown against Barton-Wright’s lead thigh.

Above: Vigny (right) seizes and traps Barton-Wright’s stick and executes a backhand strike with his own stick.

Above: Having parried Barton-Wright’s thrust with an alpenstock (spiked walking staff), Vigny (right) again seizes Barton-Wright’s weapon and counters with a backhand strike to the face.

Above: After parrying Barton-Wright’s attack with a heavy staff, Vigny (right) traps and seizes the staff and demonstrates two alternative counters; a downward cut to Barton-Wright’s lead wrist and a low backhand strike to Barton-Wright’s left knee/shin.

Above: Barton-Wright (left) presses below the elbow of Vigny’s weapon arm, disrupting his balance and opening him to a variety of follow-up attacks.

Above: Barton-Wright (left) presses into Vigny’s chest as he prepares a foot sweep against Vigny’s lead (right) foot.