- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Friday, 28th October 2016

Note – The March, 1899 antagonistics exhibition at the London Bath Club was widely reported upon in the media. Most accounts agree that the advertised Bartitsu contest between E.W. Barton-Wright and wrestler Eric Chipchase had been cancelled because both men had been injured in a cab accident the night before, but reports vary significantly on the amount and type of demonstration that did in fact, take place.

As noted below, Barton-Wright and Chipchase did come to grips about a month later during another exhibition at the St James’s Hall.

It’s also worth noting that “chucker-out” was Edwardian slang for a doorman or bouncer, who might be employed in saloons or at boisterous political rallies. Barton-Wright seemed to be annoyed by the suggestion that Bartitsu should be used in this way, and explictly refuted it in several lectures and interviews, probably because he intended the art to appeal to members of the educated classes.

Sporting Times – Saturday, 11 March, 1899

A big platform covering the centre of the bath, decorations of red and white in stripes, the level space round the bath and the gallery crowded with ladies and gentlemen in their evening finery, band in red mess jackets making music at intervals, Mr. W. H. (we used to call him Billy at Monkey’s) Grenfell in black velvet sitting aloft with a table and bell before him, Captain Hutton, also in black velvet, and carrying a rapier, on the platform, that was what saw when I made entry into the Bath Club on Thursday evening.

The special attraction was have been an exposition of the noble art of Bartitsu, by Mr. Barton-Wright; but very early in the evening Mr. Grenfell rose and told us that Mr. Barton-Wright and Mr. Chipchase, the middleweight wrestling champion, with whom he was to have had a bout, had been upset while driving together in a hansom, and that one had strained his leg and the other put out his shoulder, Mr. Wright could and would talk but could not wrestle, bartitsu, or what ever the correct expression may be; but to make up for this disappointment were to have some swimming and a bout with the gloves, as well as some extra turns of Elizabethan sword-play.

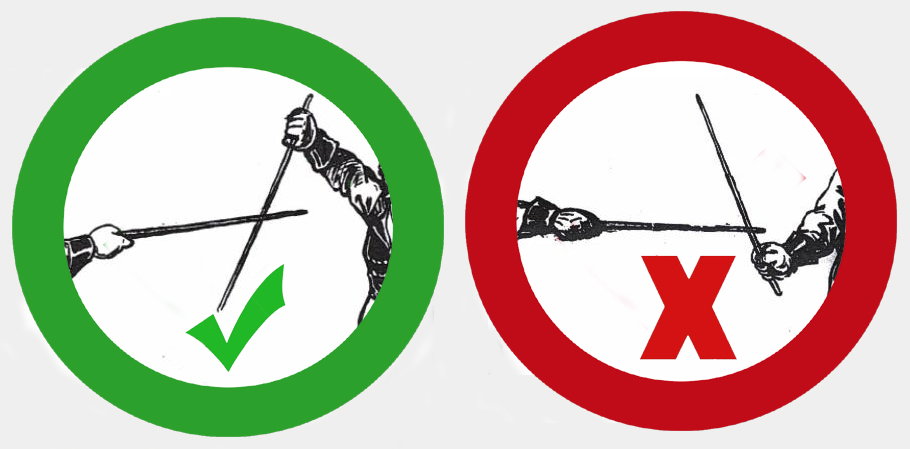

The Elizabethan sword play is always interesting. It takes an expert to tell exactly what two men with foils are doing, but any lady can understand a cloak and rapier, or a rapier and dagger fight. The contests have a picturesqueness, too, which is lacking in fencing. Sandwiched between the various combats were swimming exhibitions, and a grey-headed gentleman frequently ran his face up against pair of boxing gloves on the hands of professor somebody-or-another.

Then Mr. Barton-Wright, a spare, lightly-built gentleman, stepped on to the platform, took off his coat and waistcoat, and proceeded to explain Bartitsu as well as a game leg would permit. It would not be fair to judge the system by what was, owing to the unlucky tab accident, a lecture almost entirely without illustrations; but I saw enough interest in the subject.

“If he once gets his grip on a man, he is done,” said a very old amateur boxer to me, and the “locks” are certainly, some of them, terrific in their strength. The only question is whether a boxer might not get in disabling blow before Mr. Barton- Wright could get his persuasive hands upon him. To chuckers-out, policemen in rough quarters, and men who go where there is trouble around, Bartitsu undoubtedly will be useful; but it requires, I should say, an athlete’s training.

Sporting Times – Saturday 29 April 1899

Mr. Barton Wright—who has not quite, I am sorry to say, recovered from his cab accident—lectured on and gave an exhibition of Bartitsu at St. James’ Hall, on Monday. He wrestled a bout with Mr. Chipchase, the middle-weight amateur champion, and certainly held his own, though both men were hampered the smallness of the stage.

The chucker-out science was, as before, the most interesting part of the lecture. My previous impression that Bartitsu is most useful to a small athletic man who may have to encounter a big man is confirmed, and I certainly think that policemen, chuckers-out, and others who have to deal with troublesome characters, should study the science. The presence of Sandow’s manager nearly led to a little breeze at one period of the lecture.