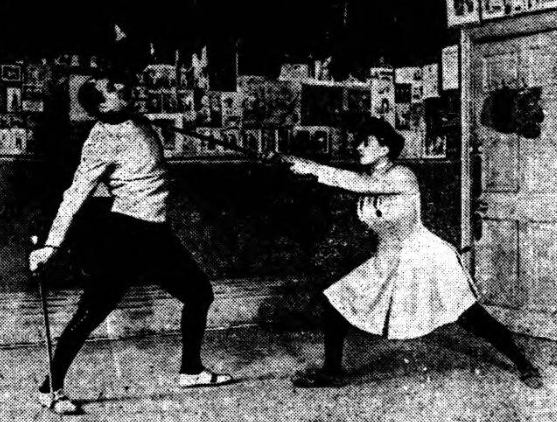

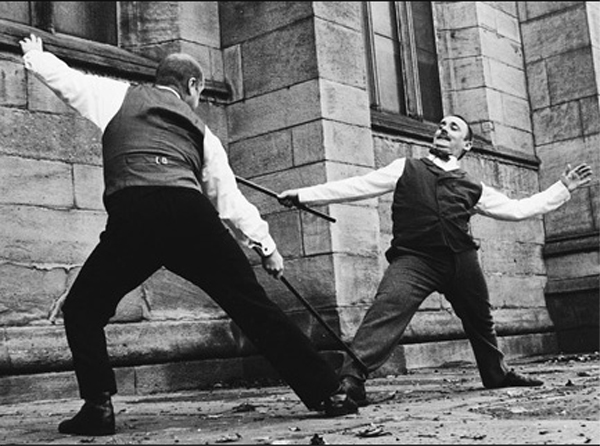

Back in 2015, the popular comedy series The League skewered/paid tribute to Bartitsu in its episode titled “Draft of Innocence”.

Better seven years late than never, here are the two short Bartitsu scenes featured in the show.

For context, the first scene introduces Bartitsu via dinner party conversation with the insufferable “sapiosexual” couple Andre and Meegan (inspiring instant and deep scorn among their friends). In the second scene, however, Andre – “kung fool” and “Tae Kwon Douche” though he may well be – saves everyone from a group of (justifiably) angry Chinese restaurant workers via his surprisingly effective mastery of the New Art of Self Defence.

Note that the second scene features some mildly risqué humour.