- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Saturday, 3rd February 2018

The article “L’Art de la Canne” originally appeared in the Revue Olympique of May, 1912. The anonymous author provides a rare technical description and some analysis of Pierre Vigny’s stick fighting system during the post-Bartitsu Club period, after Vigny had left England and returned to Geneva, Switzerland.

A translation of this article was published in the first volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (2005); the following revised and annotated translation offers some updated information and references.

The text begins:

It is all very well to learn how to use “noble”, but unusual weapons such as the sabre, the epee or the rifle; it is even better to superimpose upon this knowledge the management of the weapon that we hold most frequently in hand but of which, it must be admitted, few of us know anything in terms of effective use.

There does exist an art of the cane, but that cane recalls the gymnastic “horse” which is not constructed to resemble the animal in such a way as its exercise can be practically useful. The assaut (sparring) stick is a small, short, light wand, which is neither a baton nor a whip; a hybrid weapon for which no occasion will ever arise to use in earnest.

The author refers to the canne d’assaut, a slender, somewhat flexible stick for relatively safe fencing in the salle d’armes.

When you know how to use the assaut stick and you then pick up your walking stick – rigid, stronger, heavier and of a different length – you are in no way prepared to use your stick for your own defence. And so the opinion has been formed that the so-called walking stick is a worthless weapon.

Prof. Pierre Vigny, who taught at boxing clubs in London and at the military School of Aldershot and now runs a “Defensive Sports Academy” in Geneva, has demonstrated that (the canne d’assaut method) was nothing and that his own method, in addition to constituting an excellent system of gymnastics, leaves little to be desired in terms of practical application. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to explain (the Vigny method) other than by direct instruction. An illustrated manual might succeed in ways that cannot be claimed for a short article. So, we will confine ourselves to an attempt to indicate the characteristics of this method, whose expansion is to be desired.

The need to acquire a great flexibility of the wrist is just about the only similarity between this new fencing and the cane fencing that is taught elsewhere. The guard and strikes are very different. The guard is essentially a combat guard. The left arm is forward as if it were holding a shield; the right arm is raised back with the weapon overhead in, so to speak, a perpetual “back-swing”.

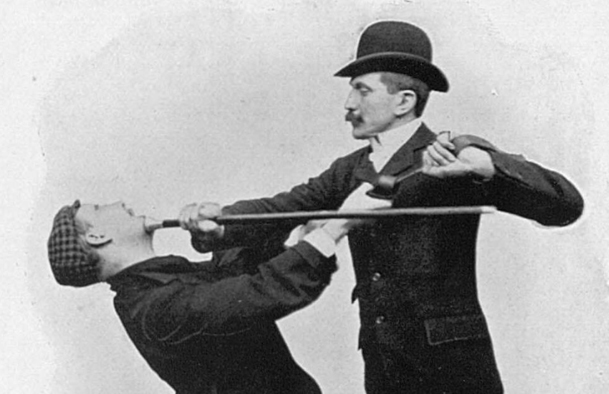

The French term here is prise d’elan, also implying a state of momentum poised before release, like a compressed spring. This guard is described by E.W. Barton-Wright as the Left Guard or Rear Guard, as demonstrated here by Pierre Vigny (on the right):

You are attacked; a brief retreat with a rapid change of guard and your cane falls mightily onto the hand or arm of the aggressor. You are almost mathematically certain to reach and damage it.

This is the Guard by Distance from the Rear Guard, as described by Barton-Wright and illustrated in Self Defence With A Walking-Stick:

After which, you advance upon him while quickly turning your wrist, thrusting the steel ferrule of the cane like a dagger into his eyes or beneath his nose. And here is a man … amazed!

The use of the ferrule end of the cane as a dagger thrust into the opponents face or throat was referred to by Barton-Wright and described by a number of practitioners and observers of the Vigny style circa 1900, most famously Captain F.C. Laing. Here Pierre Vigny himself demonstrates the technique against a belt-wielding hooligan:

The other strikes are usually whipped. Although M. Vigny calls some strikes “whipped” and others “wrapped” in order to distinguish them better, you must always get the whistling sound of a whip.

The term used here is enveloppé, which can be translated as “wrapped” or “folded”, but the technical implication is unclear. Speculatively, it’s possible that a “whipped” strike delivered a slashing or glancing impact whereas a “wrapped” or “folded” strike was a direct, percussive blow.

The little “riding crop” cane will whistle when swung without much effort. The rigid cane will not whistle unless you handle it with real vigour. Where does this force come from? From the shoulder and in the reins.

This word implies the lower part of the back; the muscular structure of the body on both sides of the spine between the lowest (false) ribs and the hipbones.

You must attain serious mobility of the reins and a wide range of movements of the arm, operated by the shoulder.

Unlike the fencing of the light assaut cannes, managing the momentum of the heavier, asymmetrically-weighted Vigny cane often, though not always, requires a whole-body engagement. The shift of weight from foot to foot that “powers” this type of action is transmitted into the cane via the legs, hips, back, shoulder and arm.

Of course, the teaching is given on the left as well as the right. The left will not be as strong as the right, but must be able to provide for it on occasion.

Here the author evokes the characteristic ambidexterity of the Vigny style, as from the double-handed guard position:

There are also bludgeoning strikes that require a special preparation. There is nothing like it in other styles of fencing.

Possibly a reference to the use of double-handed striking:

And the muscles, at first, do not want to accommodate. They contract incorrectly; the force is lost en route and the blow arrives low and as if cushioned. There must be, so to speak, an internal continuity between the cane and the arm that extends it. Without stiffness, but with a tensile force, the wrist must become like a knot in the wood. For this reason we hold the cane with a full grip, the thumb folded on the other fingers and not lengthened against the cane. This habit is difficult and somewhat painful to acquire. The palm wrinkles and blisters and the muscles register tension and pain, but this is the price of efficiency.

The Vigny method requires not only that the body is always well-balanced, but also that it sustains equilibrium in perpetual motion. In this, it is akin to Ju-jitsu. It has the disadvantage of not allowing the assaut between average amateurs (students); to truly spar in such a sport would be to expose oneself and one’s partner to the risk of severe injury. Therefore, one must stick to the prescribed lesson or engage in a mock combat with the professor. But does this not, in fact, commend it as an exercise of defence?

The Vigny style was, in fact, used in sparring bouts, at least during the Bartitsu Club era and afterwards at Vigny’s own academy in London; though ironically Pierre and Marguerite Vigny may have employed the canne d’assaut for that purpose, as shown in this photograph: