- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Friday, 28th March 2014

The explosive success of the Sherlock Holmes movies have embedded an awareness of Victorian-era martial arts into the popular imagination. In the wake of that success, it may be useful to offer some recent history and an explanation of the terms “canonical” and “neo” in the context of the Bartitsu revival.

Back in the very early 2000s, Bartitsu Society conversation turned from purely academic chat to considering how to bring the art back to life. At that time, although the active participants came from a wide range of martial arts backgrounds, almost all of us had experience in the historical European martial arts (HEMA) movement.

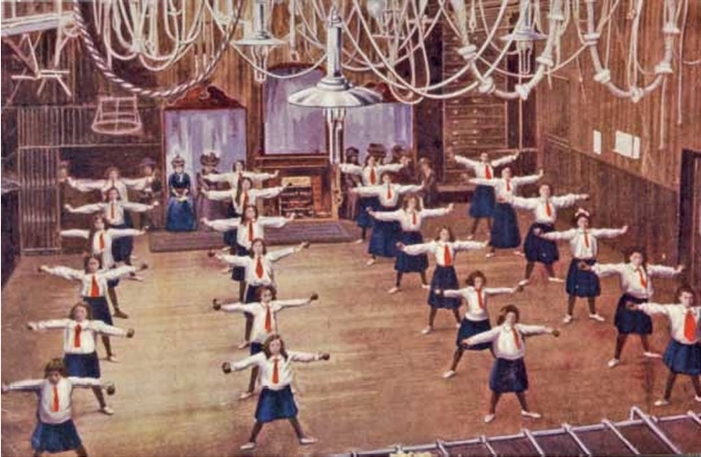

The task of reviving Bartitsu was seen very much in HEMA terms, with several caveats; it was uniquely a cross-training method between certain Japanese, English and French/Swiss antagonistics, and, unlike many HEMA revivalists, we did not have a complete technical catalog to work from. Thus, we would effectively be reviving an experimental work-in-progress rather than a finite system.

Many of the first generation of Bartitsu revivalists had been active martial artists long enough to have seen the worst of politics in other arts; friendships destroyed and long-running inter-group feuds arising over matters of technical interpretation, etc. Forewarned is forearmed, and so we decided early on that the Bartitsu Society would remain an informal association of colleagues rather than a bureaucratic “governing body”. To mitigate the chance of our efforts being sidetracked by tiresome politics, we proposed a two-tiered structure for the nascent Bartitsu revival.

The Bartitsu Canon

The first level or approach would be “canonical”, a term borrowed from Sherlock Holmes scholarship to describe “Bartitsu as we know it was”. This included the formal self defence set-plays and techniques presented under the Bartitsu banner by Barton-Wright and his colleagues, circa 1899-1901. Originally, the canon was restricted to Barton-Wright’s article series for Pearson’s Magazine, which had then only recently been publicly broadcast via the Electronic Journal of Martial Arts and Sciences website. As we continued our research, the canon gradually expanded to include:

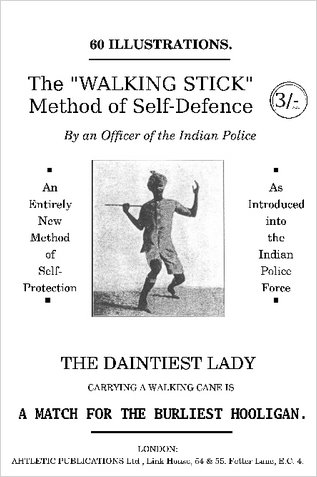

* B-W’s four articles for Pearson’s Magazine, covering jiujitsu and Vigny stick fighting

* Mary Nugent’s article on the Bartitsu Club for Health and Strength Magazine, which included a couple of jiujitsu techniques

* Captain Laing’s 1902 article on the “Bartitsu Method of Self Defence”, covering Vigny stick fighting

* fragments from other sources including a single unarmed combat technique that appeared only in the American edition of Pearson’s, another that was specifically credited to B-W that appears in Longhurst’s Jiujitsu and Other Methods of Self Defence, B-W’s technical comments in other sources and what can be gleaned from incidental material (illustrations accompanying Bartitsu articles produced during the Club era, etc.)

The canonical set-plays from Pearson’s provided a “common language” for Bartitsu revivalists, offering a finite corpus of technical and tactical guidelines. They were also our most direct link back to the original art, as presented by its founder and original practitioners, comprising a body of “living history” knowledge. This was a crucial point, and of intrinsic value, from the HEMA perspective.

Neo-Bartitsu

It was clear, however, that there was more going on at the Bartitsu Club than the set-plays that happened to be recorded on paper. Barton-Wright and his associates had offered numerous clues and hints as to the full scope of the art via their interviews and demonstrations. In order to fill in the gaps in the historical record, we also proposed a second, complementary approach, referred to as neo-Bartitsu. As with all HEMA revivals, the object was to recreate the original style as closely as possible, via highly educated guesswork.

Within the context of the Bartitsu revival, “neo” refers to using a body of “old” techniques in a new context; it describes both “Bartitsu as it may have been” and “Bartitsu as it can be today”. Specifically, neo-Bartitsu refers to the modern practice of the canonical material augmented by the vast body of martial arts, self defence and combat sport lore recorded by Bartitsu Club instructors and their first generation of students, dating into the early 1920s.

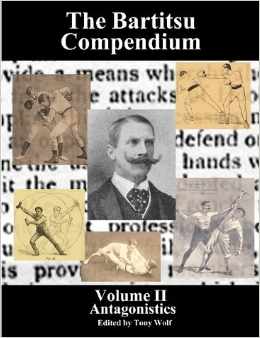

In designing, compiling and editing the second volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (2008), we deliberately presented a set of interlocking resources for neo-Bartitsu, rather than a prescription of lesson-plans. It was felt that establishing a single “unified curriculum” would stifle individual initiative and takemusu (martial creativity), homogenising the revival and ultimately leading to the political entanglements we all wanted to avoid. By leaving the curriculum open to experimentation and the revival movement unregulated, we hoped to foster a grassroots consensus of what Bartitsu may have been and could be.

Thus, the material in Volume 2 was very carefully selected from mostly “Bartitsu Club lineage” sources, edited to avoid redundancies and repetitions while offering great scope for individual variations. It was unified by a set of principles and themes redacted from Barton-Wright’s own writings.

“Krav Maga (etc.) in straw boater hats”

For almost all practical purposes, every modern Bartitsu revivalist trains in a combination of canonical and neo- forms of the art. “Neo-“, however, is not interpreted as carte-blanche license to promote any given melange of fighting styles under the Bartitsu banner. Prior to the success of the Sherlock Holmes movies, members of the Society used to joke about that eventuality, on the assumption that the art would never become popular enough for it to actually happen.

The substantial addition of techniques from disparate, historically unrelated sources is sometimes justified by the assumption that Barton-Wright “would have” done the same thing if, for example, Krav Maga, Thai kickboxing or Filipino stick fighting had been available to him. Alternatively, it has been argued that, since Bartitsu was originally an eclectic method, adding considerable new (“neo-“) material from various sources is in the spirit of his original method.

The counter-argument is that the further one moves from the original, canonical and lineage sources, the less sense it makes to refer to the result as “Bartitsu”, neo- or otherwise. By the same token, since numerous effective arts combining stick fighting, kickboxing and grappling already exist, proponents of the “anything goes” school of thought run a strong risk of re-inventing the wheel.

While (neo-)Bartitsu does represent the art as it may have been and as it can be today, that presupposes a truly thorough understanding of what it probably was. The revival is, therefore, deliberately and specifically anachronistic, focussed on the Bartitsu Club of London circa 1901 and on the people who began the cross-training experiment that we have “inherited”, one hundred years later.