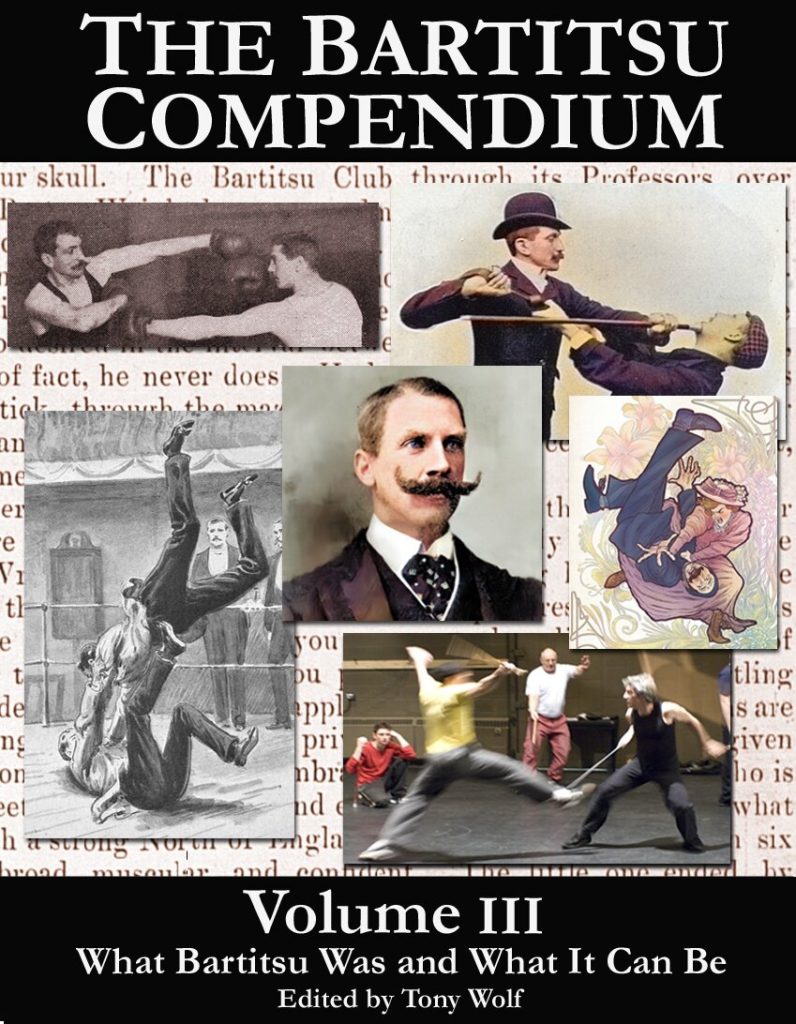

Published 120 years after the Bartitsu School of Arms in London closed its doors for the last time and marking the 20th anniversary of the modern Bartitsu revival movement, the Bartitsu Compendium, Volume III is now available from Amazon.

Over six hundred pages in length and profusely illustrated with rare historical images, Volume III represents the cutting edge of current knowledge on Edward Barton-Wright’s “New Art of Self Defence”.

The book is divided into four sections:

Drawing from two decades of intensive research, The Bartitsu Story is the first truly comprehensive, long-form social history narrative of the rise and fall of Edward Barton-Wright’s “New Art of Self Defence”.

This 160+ page essay includes previously unrevealed aspects of Edward Barton-Wright’s biography as well as in-depth analysis of the evolution of Bartitsu as a martial art.

The Antagonistics Anthology compiles the 50 best historical articles from the Bartitsu.org site (now BartitsuSociety.com) in addition to a collection of new articles of diverse interest to Bartitsu enthusiasts, including:

- Behind the Scenes of Jiu-Jitsu Downs the Footpads, or, The Lady Athlete – A Pioneering Martial Arts Movie Shot in 1907

- “Making the ‘Knock-Out’ Safe”: Innovations in Boxing Safety Equipment (1895-1913)

- The Gentlemanly Arts of Self-Defence on the Small Screen

Techniques and Tactics highlights the key “style points” that distinguished Bartitsu from other self defence systems at the turn of the 20th century, with entries including:

- “Not at All Like the Guards Taught in Schools”: Bartitsu Tactics of Unarmed Defence

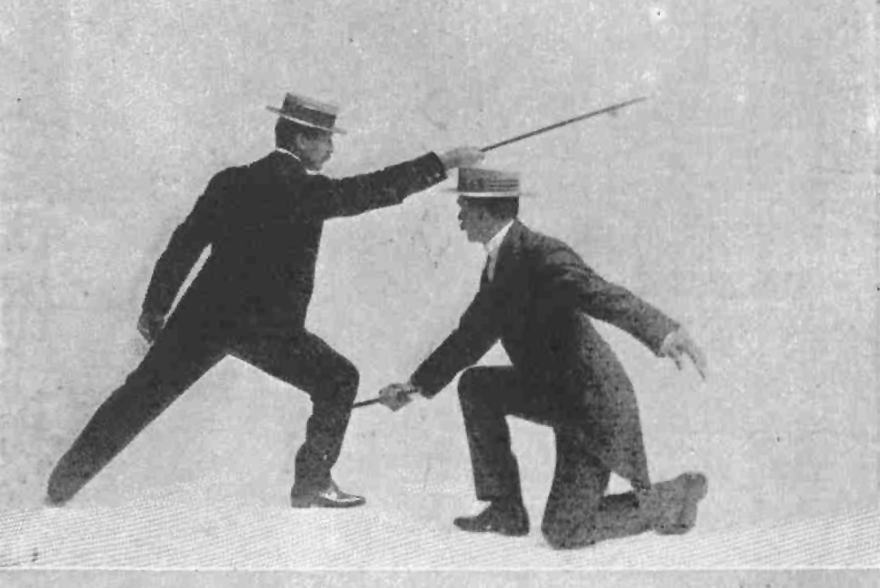

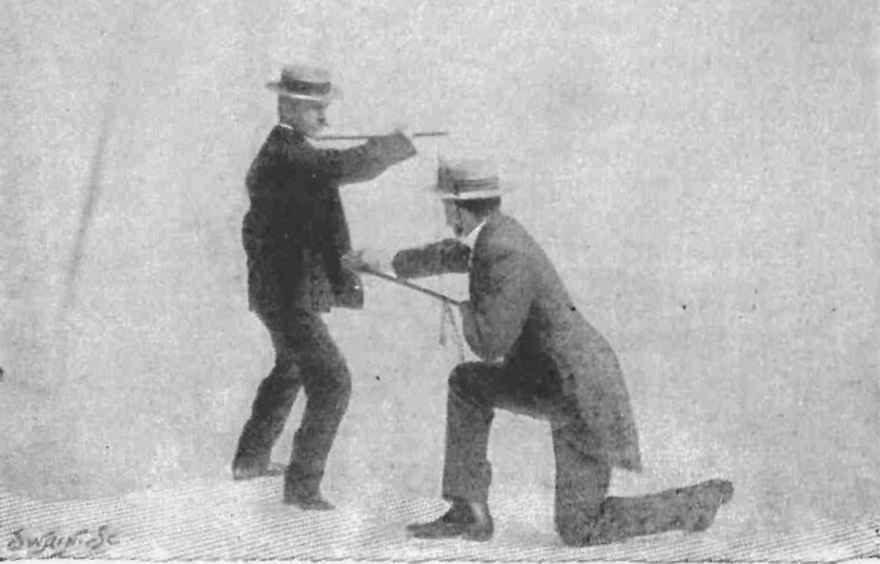

- Style Points: Key Techniques and Tactics of Vigny Stick Fighting

- Captain Frederick Laing’s “Practices” & “Examples” of Bartitsu Stick Fighting, Illustrated

The final section, Revival and Legacy, offers a look back at the first 20 years of the Bartitsu revival via the activities of the Bartitsu Society and the impact of Barton-Wright’s “New Art” art on modern pop-culture, with entries on diverse topics such as:

- “Engaging Toughs” – Bartitsu Sparring

- Why Bartitsu is for Everyone

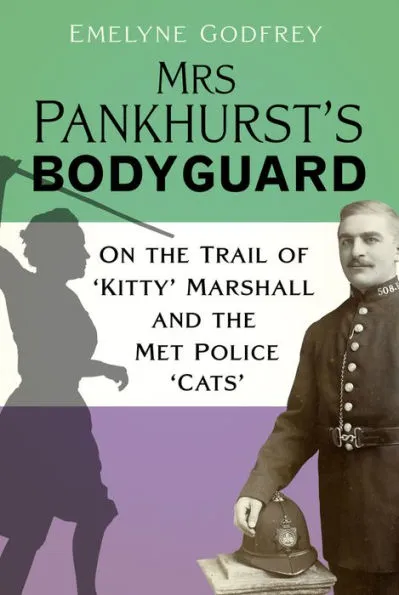

- Creating “Suffrajitsu: Mrs. Pankhurst’s Amazons”

“What Bartitsu Was and What it Can Be”, by Tony Wolf

I first proposed the ideas of “canonical” and “neo”-Bartitsu back in the very early days of the Bartitsu revival, circa 2003. The canon included all the materials presented under the Bartitsu banner by Edward Barton-Wright and his associates at the turn of the 20th century, whereas neo-Bartitsu comprised “Bartitsu as we know it was and as it can be”.

These conceptual approaches were necessary because, unlike many other historical martial arts revivalists, Bartitsu enthusiasts did not have a full technical catalogue to work from. Barton-Wright had offered detailed instructions in some areas but only cryptic clues and hints in others. Thus, the Bartitsu revival was a historical mystery box; a matter of piecing together hard-won evidence, gathered from antique book stores and obscure newspaper archives over the course of many years, before pressure-testing our discoveries in the gym.

The first volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (2005) presented the canon and the second volume (2008) offered further resources for revivalists via a curated cross-reference of works produced by former Bartitsu Club instructors and their first generation of students, dating into the early 1920s.

Volume III draws from the past 20 years of intensive research towards authoritatively answering the question of “what Bartitsu was” as well as indicating “what it can be” on that basis, arguing that Barton-Wright’s “New Art” was – simultaneously – a method of cross-training between several systems of circa 1900 antagonistics and a unique martial arts style in its own right. That style deserves careful attention and development by current and future Bartitsu revivalists, towards continuing the experimental work-in-progress that originally ended in 1902.

This volume also extends the theme of Bartitsu as a window into social history. If Barton-Wright’s “New Art” was a stone dropped into the pond of London society at the turn of the 20th century, then the ripples extended out into popular culture (everything from music hall ballyhoo to the Sherlock Holmes stories) and into social movements including “Orientalism”, physical culture, feminism and the moral panic over the so-called “Hooligan menace”. Looking back over the first 20 years of the Bartitsu revival offers a surprising perspective on how history repeats itself.