Our 2017 article on the Bartitsu Club’s “grand tour” of exhibitions during early-mid 1902 included several detailed reports on the event staged at the Oxford Town Hall. One of those reports offered the intriguing detail that a Mr. Whittle, who was the university’s heavyweight boxing champion, had undertaken a bout with the Japanese champions. It was, however, unclear whether this had actually been a “boxing vs. jujutsu” contest – which would have been an extraordinary novelty in 1902 – or whether the athletic Whittle had simply agreed to try his hand at competing under jujutsu rules.

The following report from the Oxford Journal of Saturday, March 1st 1902 appears to confirm the latter scenario:

JAPANESE WRESTLING AT THE TOWN HALL.

An entertainment which was both instructive and interesting was given in the Town on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings. The attendance was decidedly disappointing, while one or two events which had been anxiously awaited, vis, the Bartitsu defence with an ordinary walking stick and the Savate v. Boxing contest, had to be omitted owing to the indisposition of the contestants.

Nevertheless, the exhibitions given seemed to be thoroughly enjoyed and met with hearty appreciation from an audience largely composed of ‘Varsity men. Mr. Barton -Wright, the founder of the system, offered £20 to anyone who could defeat his champions, who have recently been engaged at the London Empire, where they defeated all comers, no matter how strong or big. That is the great point about this particular method. As Mr. Wright, founder and proprietor of the Bartitsu Academy of Arms and Physical Culture, said in his opening remarks, to be successful a man need not necessarily be strong or heavy. A child who had his head screwed on the right way stood much chance as the strongest man in the world, an assertion which was proved by subsequent events, when Mr. Whittle, the amateur heavyweight boxing champion of the ‘Varsity, ascended the platform and attempted to throw one of the Japanese champions, but was thrown by the Jap. after a severe bout.

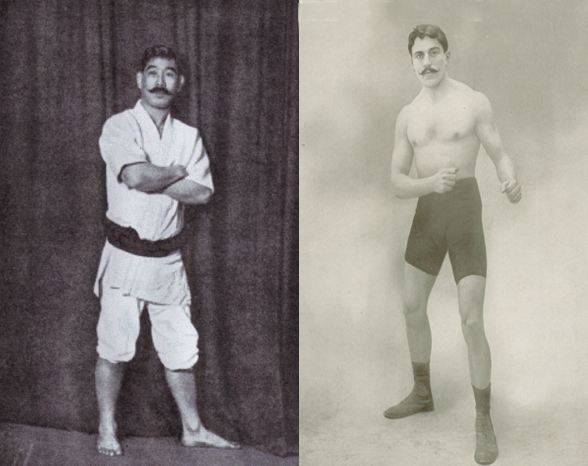

The first item on the programme was an exhibition of the secret art of Japanese self-defence. Mr. Wright explained that this form of defence had never been allowed to be shown in Japan, much less in Europe, and this was the first time the men had ever appeared in public. In Japan the only person s allowed to learn were members of rich families and Government officials. As the champions made their appearance they were given a hearty reception. They are both young, Uyeniski (sic – should read Uyenishi) being 22 years old and Tani 21, and weigh about 9 stone. The former is the light-weight champion of Japan and Tani the boy champion of Tokio.

Each advanced to the end of the platform, and then walked towards one another, Uyeniski attacking and Tani defending. When at close quarters the former made a thrust with his hand and caught hold of his opponent’s hair and grappled with him. By a dexterous movement, which requires to be seen to be properly understood, Tani freed himself and threw the champion to the accompaniment of hearty applause. It is certainly gratifying to know that even the strength of a Sandow can be successfully resisted by a light-weight knowing this method.

Another of the many instances in which the method is useful is in the event of an attack from behind with some blunt instrument while seated on a chair.

In the next item four strong men were invited to ascend the platform and strangle one of the wrestlers. Tani then lay at full length on the platform with a pole across his throat. On each end of the pole were two strong men, including Mr. Hugh Wyld, the O.U.A.C. secretary, and Mr. Whittle. At a signal the four men put all their weight on to the stick, but in less time than it takes to tell it Tani had got rid of his burden and was free, leaving the four men still bearing on the pole. The two youthful champions wrestled in Japanese style, in which the clothes are made use of to obtain holds end grip. The advantage, it was explained, of this style over any other was that it is absolutely natural and most practical. Weight and strength, as in the self-defence, only play a minor part everything depending on skill.

Another interesting bout was that between the champion heavy-weight Cornish and Devon wrestler and Uyeniski, the latter throwing his opponent three times. Tani then gave an exhibition of falling in dangerous positions without being hurt, and the entertainment concluded with a 925 catch-as-catch-can contest for the championship of England, which was to have been between William Clark (professional champion of the South of England) versus A. Cherpillod (Bartitsu instructor and champion of the world). Clark being unable to appear owing to vaccination, Zara, the Swiss champion, was brought down at short notice. The bout lasted an hour and was fiercely contested, but in the end neither wrestler had been successful in securing a throw and a draw was the award. The champion’s also gave a wrestling bout as used by Swiss shepherds. This lasted for a quarter-of-an-hour and again no throws were recorded. The entertainment lasted for about two hours.

The “Swiss shepherd” style referred to was almost certainly schwingen, at which Cherpillod was an acknowledged expert in addition to his accomplishments in catch-as-catch-can.