- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 31st January 2017

Here follow two further reviews of the series of self-defence exhibitions organised by Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright during mid-1899, to benefit Pierre Vigny, who had then recently arrived in London.

Vigny was noted in related reports to have started his study of English boxing at the age of fifteen and had begun to work as a master-at-arms from the age of twenty-three. He had initially travelled to London, at least in part, to gain further experience in the English style of fisticuffs, and indeed had competed in several bouts with English boxers shortly after arriving in the city during late March of 1899.

Vigny, of course, went on to collaborate with Barton-Wright in the practical development of Bartitsu as a “mixed martial art” and assumed the role of Chief Instructor at the Bartitsu School of Arms between 1900-1902. He later set up his own London school before returning to Switzerland and continuing his work as a self-defence and physical culture instructor.

From the Sporting Life: Tuesday, 27 June, 1899:

“WALKING STICK PLAY: BARTITSU LADIES’ NIGHT”

For the purpose of introducing to the English public Professor Pierre Vigny, the celebrated French swordsman and world champion of walking stick play and la savate, and also as a benefit to that gentleman, Mr. Barton-Wright organized a grand display of various forms of self-defence, which took place on Thursday evening in the Banqueting Hall, St. James’s Restaurant, Regent Street . W., which was well attended by a fashionable and appreciative company, including many of the fair sex, in full evening dress.

Mr. Barton-Wright, the initiator of “Bartitsu”, gave a descriptive lecture and demonstration of walking stick play and la savate with Professor Pierre Vigny, who will instruct in these two subjects at the Bartitsu School of Arms, which will shortly be opened in a central position in the West End.

Without question, Professor Vigny is an undoubted master of these two forms of self-defence, and to which he will devote special attention at the Bartitsu School of Arms, but whether these two forms of self-defense will readily be taken up by Englishmen remains to be seen. Anyhow, to become proficient in these, it will require a vast amount of practice, and in gaining this plenty of beneficial exercise will be necessary, and this alone will commend itself to be rising and present generation of athletes.

The entertainment throughout was of a highly interesting character, and as all concerned in it were adepts in their several styles, everything passed off satisfactorily and in the most efficient manner. The chief events comprising the program were –

Fencing foils

Mr. W. H. Staveley (London Fencing Club) v. Mr. W. P. Gate (London Rifle Brigade) – these able exponents had a grand bout, Mr. Gate gaining last hit.

Walking stick play

After an explanation of the procedure and demonstration with Mr. Barton-Wright, Professor Vigny engaged in a most spirited bout with Professor Anastasie, of Paris, both displaying great aptitude with the walking sticks.

Boxing

Lieutenant Ronald Miers (middleweight amateur champion of the Army) v. Tom Burrows (champion club swinger) – a splendid three rounds in which both showed fine science, which was much appreciated, especially by the ladies.

La Savate

Professor Vigny (champion of the world) v. Professor Anastasie (of Paris) – an interesting bout in which both concerned showed great agility in their feet work, especially Vigny, who gained the last point.

Mr. Barton-Wright, who claims to have put forward a new style of defence, especially in dealing with heavyweights at wrestling and otherwise, gave an exhibition of his system with one of the audience, and fully demonstrated his power, but in actual contest he would have to wait his chance of getting on all his holds against a proficient opponent.

Professor Vigny also engaged in a bout with walking sticks against two professors, and gave a clever exhibition of his undoubted superiority with these weapons. Professor Vigny is also a proficient with the gloves under the Queensberry rules.

From the Sporting Life – Saturday, 22 July, 1899:

“WALKING STICK PLAY and LA SAVATE”

Mr. Pierre Vigny, universally acknowledged as the best exponent of walking stick play, gave a most interesting and novel demonstration of this art of self-defence a few nights ago before a very distinguished and select audience at one of the most fashionable London clubs.

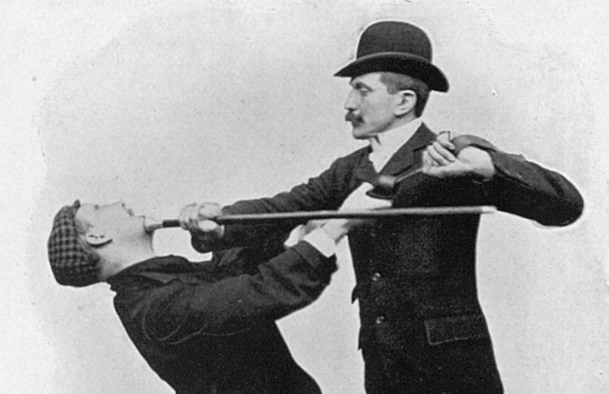

He first proceeded to demonstrate the use of the stick by showing the different attacks and guards, displaying wonderful wrist work, in which great strengths and suppleness were combined. He grasps a stout Malacca cane about six inches from the end, and does all the movements with the wrist only, and not with the fingers. He passes his stick from right hand to left and vice versa without the slightest trouble, using right-hand and left-hand alternately with equal dexterity. He then took a stick in each hand and gave a wonderful display of combined right and left-hand work, showing great activity and science.

After this he engaged in a bout with Mr. Anastasie of Paris, a well-known professional exponent of walking stick play and la savate. The weapons used were thick Malacca canes and it must here be observed that no masks, gloves, nor padded jackets were worn. Both exponents appeared in tights only, and wore no protection of any sort. The stage was small and did not admit of the exponents getting away to avoid punishment, and therefore they had to face the music, which was very lively and real. But, in spite of the pace and the formidable weapons used, it was effectively proved that an able exponent of walking stick play never gets hit upon the fingers and so disabled and disarmed.

Mr. Anastasie, a small, agile man, faced his redoubtable opponent with great courage, and displayed considerable skill, but was outclassed by his bigger and more scientific opponent, and Mr. Vigny conclusively proved that, even at close quarters, it is practically impossible to hit him with a stick.

After a short rest Mr. Vigny and Mr. Anastasie gave a display of la savate, and as they are both especially good exponents the demonstration was exceedingly interesting. Mr. Vigny will give a public demonstration of walking stick play, la savate, boxing, swordplay, fencing, and Indian clubs at an early date at the St. James’s Music Hall and we can confidently recommend our readers to go and see him.

Both walking stick play and la savate are included in Mr. Barton-Wright’s system of self-defense, which he calls Bartitsu, and will be taught at the Bartitsu Club which will shortly be started in some central position in the West End. The following gentlemen will be the first directors of the club – W. H. Grenfell, President; Lord Alwyne Compton, M. P., Chairman; Lord Arthur Cecil, Bertram Astley, W. Moresly Chinnery, Captain Alfred Hutton, St. Clair Stobbart, W. Montague Sweet, and Mr. E. W. Barton-Wright, managing director.