- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 10th January 2019

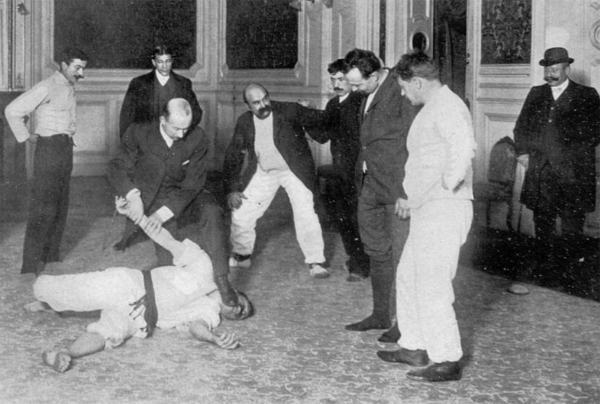

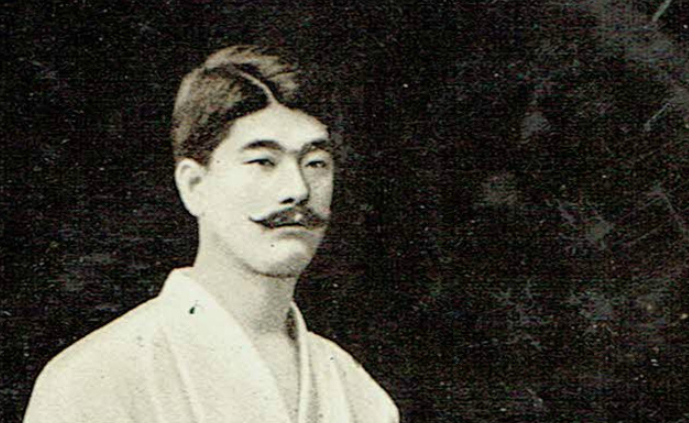

After the Bartitsu Club closed in mid-1902, most of the instructors continued independent careers as instructors and combat sport athletes. Although Sadakazu Uyenishi was better-known as an instructor than as a challenge wrestler, he did successfully tour the music halls “taking on all comers” under his professional pseudonym, Raku.

In August of 1906, Uyenishi’s engagements brought him to Belfast, Ireland, where he made the news for something other than his martial arts proficiency. This event was reported in a number of regional papers, including the Belfast Weekly News:

EXCITING SCENE AT QUEEN’S BRIDGE

Rescue by a Japanese Wrestler

Raku, the Japanese exponent of Jujitsu wrestling, who has during the week been appearing at the Palace, was walking across the Queen’s Bridge yesterday afternoon, in company with Mr. Harris, the manager of the Palace, when they noticed a man struggling in the water. Without the slightest hesitation the Jap. divested himself of his coat, and running down to the Bangor Jetty dived into the water.

Raku, who is a powerful swimmer, soon reached the drowning man and succeeded in keeping his bead above water until ferryboat came to the rescue. The men were landed at the ferry steps near the Queen’s Bridge, and – the famous wrestler having applied the Japanese method artificial respiration – the man soon recovered and was able to proceed home. It appears that he fell into the water from a boat while endeavouring to recover a lost oar.

In fairness, these events may well have played out exactly as reported. Uyenishi was, by other reports, a good swimmer and all-round athlete, and either he or Tani had previously been reported as having applied a kuatsu-style resuscitation technique to bring around an unconscious wrestling opponent.

It would be remiss, however, not to note the possibility of “swank”. Edwardian-era show business was far from immune from staging publicity stunts to generate controversy and ticket sales. A journalist from the Northern Whig offered a very polite note of surprise, if not overt skepticism, about one aspect of the story:

The ambulance was sent for, but the rescued individual, who had been brought round by the attentions of the gallant Raku, declined to enter it, preferring to go home in a car. His name and address do not seem have been elicited either by the rescuer or the ambulance men. This was rather a pity, because, when a public character like Raku effects a daring public rescue, the public like to know something about the identity of the rescued.

The rescued man’s name and address were then, seemingly, discovered, as subsequently reported by the Belfast News-Letter:

A WRESTLER’S GALLANTRY REWARDED

At the Palace

At the second performance at the Palace on Saturday evening, an interesting extra turn was supplied when Raku, the famous Japanese wrestler, was presented with a handsome gold watch in recognition of his gallantry in saving a man from drowning in the Lagan at the Queen’s Bridge 17th inst.

It will remembered that Raku, who was engaged at the Palace last week, was walking over the Queen’s Bridge on the Friday afternoon, when he saw a man in the water. He immediately divested himself of his coat, jumped into the river, and succeeded in keeping the man’s head above water until a ferry boat came to the rescue. The rescued man, whose name is Frank Reynolds, residing in Unity Street, soon recovered, and was little the worse of his immersion.

A number of local gentlemen formed themselves together and subscribed towards the presentation to the plucky Jap. Mr. Harris, the manager of the Palace, in making the presentation, said that he had been asked on behalf of the subscribers to hand over the gold watch in a token appreciation Mr. Raku’s heroic conduct. (Mr. Harris) was sure that he was only expressing the sentiments of the audience when he hoped that the famous wrestler would be long spared to wear it. (Applause.)

Mr. Raku’s manager, in reply, returned thanks, and said Raku desired him say that he had only done what any Britisher or Japanese would have done – namely, gone to the assistance of a man who was in danger of losing his life. (Applause.)

So – in August of 1906, Sadakazu Uyenishi may have heroically saved a man from drowning in the Lagan River, or may have been the key figure in a very elaborate publicity stunt. Either version makes for a colourful story.