- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Sunday, 10th February 2019

Originally published in The People newspaper of October 23, 1904, this newly rediscovered article offers a rare glimpse into former Bartitsu Club instructor Pierre Vigny’s Hinde Street school.

Although Vigny and his wife Marguerite remained in England for some years after the Bartitsu Club closed in mid-1902, comparatively little is known about the Vigny self-defence system, per se, during that period. Reading somewhat between the lines, however, it’s apparent that Vigny’s post-Bartitsu Club style was similar to what had been taught at the Bartitsu School of Arms, albeit with a greater emphasis on fencing than on jiujitsu.

The author, “A. F.”, closes with a pot-pourri of more-or-less accurate information on boxing, including a self-defence technique borrowed from “Ruby Robert” Fitzsimmons’ 1901 book Physical Culture and Self-Defence.

One can hardly take up a daily paper without reading of street attacks by hooligans. Only a few days ago one heard of the sad case of a poor needlewoman of nearly 70 years of age who died at the Royal Free Hospital from wounds inflicted by three cowardly and despicable scoundrels; so that, consequently, when one learns that with an ordinary stout walking stick, or hooked umbrella, one can venture into the very haunts of the hooligan, one is all attention.

The idea of using any other means of self-defence then the good, time- honoured “dibs” at first appears un-English, yet one must bear in mind that the gentry who are in the habit of molesting pedestrians are absolutely unscrupulous in the weapons they employ.

One reads of the knuckleduster, buckled belts, and even bars of iron concealed in newspapers. The reader, when he calls to mind these facts, and also that the quarterstaff was formerly used by every Englishman as a weapon of defence, especially in the western parts of the kingdom, will find that any prejudice he may have with regard to the use of the stick will be of short duration.

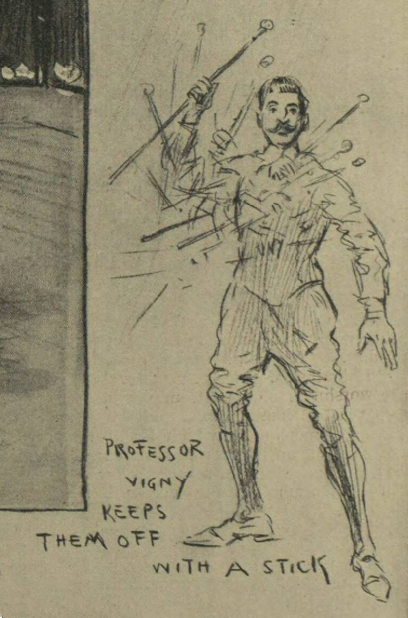

One recalls an excellent description of the use of the quarter-staff in Washington Irving’s “Dracebridge Hall,” that helps us to understand the important part this weapon formerly played in street self-defence. There appears to have been, in the reign of Henry VIII, a Devonshire gentleman who was such an expert with the quarterstaff that he was known to have held his own with this weapon alone against three opponents armed with rapiers and poniards, and, strangely enough, this is exactly what Prof. Pierre Vigny, who has an academy for self-defence in Hinde St., Manchester Square, teaches his pupils to do, armed only with a walking-stick.

The Vigny self-defense stick is a stout malacca cane about 3 feet long, crowned with a solid metal knob about the size of a golf ball. It is flexible, beautifully balanced, and, in the hands of anyone who knows the proper way to use it, sufficient to keep a crowd of hooligans at bay. Even a Fitzsimmons would have a very poor outlook were he to come in contact with a pupil of this novel school of self-defence.

The great mistake that the uninitiated make in using the walking-stick is that, after dealing a blow, the weapon is allowed to remain when it has fallen, instead of being drawn back to the position of self-defence. It is this drawing, or rather cutting, blow that is so telling, and is the foundation of Vigny’s system.

In fact, the exercises with the walking-stick that I had the pleasure of witnessing the other morning at Manchester-sq. gave me much the impression that many of the cuts resembled closely the cutlass drill of the Royal Navy, and yet Vigny’s pupils manipulated the “canne” in manner that defies desription, for the rapidity with which the stick was twirled, acting as a complete guard, and which made me instinctively shrink back in my chair, needs to be witnessed to be thoroughly appreciated. I noticed that the stick itself was held about eight inches from the end, so that after a crashing blow has been delivered it was quickly followed up by a stabbing movement with the ferrule end, which was used as if it was a dagger.

I think I can safely say, without wishing to advertise Monsieur Vigny’s appliances, that his stick in the hands of even one possessed of ordinary judgment, is sufficient to dispose of half a dozen hooligans. In fact, the professor informed me that, one winter evening when in a low quarter in Paris, he was actually attacked. I wish I had been there to see the fun.

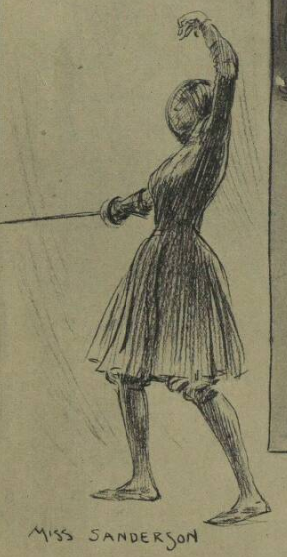

The Swiss master-at-arms also teaches his pupils how to defend themselves unarmed in the streets, a series of tricks into which la savate and Japanese wrestling are introduced. We are able to reproduce here a drawing showing Prof. Vigny in his self-defence guard for the streets, and also that splendid Australian boxer, Bob Fitzsimmons, in his “right position.”

Rather Tricky

Even Fitzimmons, with all his science, knows that one man against many is an uphill game, and consequently has several tricks at his fingertips that he can put into execution should the necessity arise. An interesting lesson in street self-defence is that given in his book on physical culture. Here he depicts an opponent threatening to start a fight with him, and a speedy method of placing his opponent at his mercy.

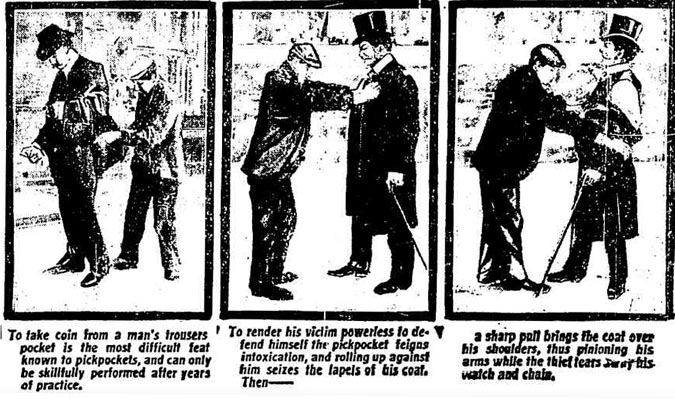

This is done by grasping his opponent’s coat by the collar on either side, and whipping it down over his back and arms, thus leaving him at his mercy, for, with the coat turned back in this position, it is impossible to bring the arms forward without first removing the garment, and while thus engaged it will be clearly seen that the opponent leaves his “oration trap” entirely at the disposal of his adversary .

Origin of the Knuckleduster

With reference to the knuckleduster as an implement still in use by hooligans, it is interesting to note in connection with this instrument of torture, and the history of self-defence, that it is a survival of the “cestus” used by the ancient Roman gladiators. This “cestus” was composed of strips of leather wound around the arm as far as the elbow, and studded on the knuckles with knobs loaded with lead. Theseus is supposed to have invented boxing – by boxing one means, of course, the skilled use of the fist and arms and assault and defense .

In heroic times fighters sought rather to be fat and fleshy in person, than firm and pliable, for they considered that, in order to withstand blows, plenty of flesh was essential. This form of the manly art of self-defence appeared in England in 1740, and it owed its introduction to Broughton, who built a theatre for pugilists in Oxford Road. It was this fighter who was champion of all England for 18 years. 55 years later a new system of boxing was introduced by Jackson, Lord Byron’s professor, by which the legs were used in avoiding blows and the correct estimate of distance (striking no blows out of range) was arrived at.

Of course, one can hardly expect to be successful in any encounter unless one keeps in fair training, and for this purpose one cannot do better than follow the Australian champion’s advice, showing how any man, who is kept indoors much of the time, may keep in fairly good trim. It sums up as follows – abstain from the use of fatty and starchy food; eat all kinds of meat except pork; eat all kinds of green vegetables, fruits and dry toast; drink tea (without sugar), and do not eat potatoes, butter, fresh bread, or sugar.

This is the diet and sit down by Fitzsimmons, and, if the middle aged businessman who is beginning to increase in weight will follow the diet laid down by the man who has done more for the cause of scientific boxing (and the art of self-defence) than any other person has ever accomplished, he will find that not only will he be free from aches and pains, but that, with a moderate indulgence in self-defence exercises, he will drop from 2 pounds to 5 pounds a week, and, what is equally to the point, never a farthing into the pocket of the troublesome hooligan.