- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Saturday, 28th August 2010

The third and final installment of Michael Bertram Wooster’s report concerns the fall of the Bartitsu Club and solves the riddle of Holmes’ “baritsu”.

In 1902, the founder of Bartitsu broke with one of his most important instructors. Barton-Wright’s relationship with Yukio Tani, difficult even in the best of times, came to an abrupt end. As the Englishman later told Gunji Koizumi:

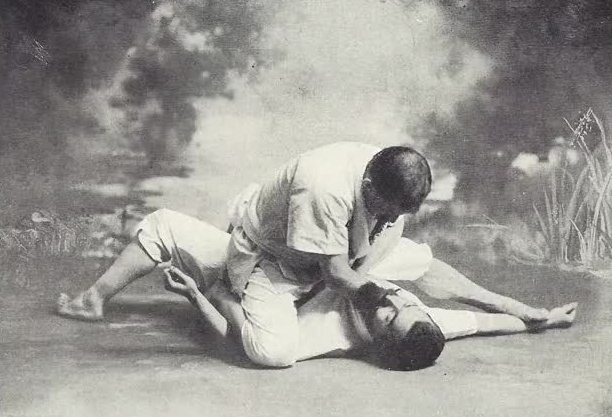

“… Tani was troublesome in keeping appointments. I proposed to make deductions from his wages. One day he was in a furious temper over it and threatened me with violence. In the conflict which followed, Bartitsu proved superior to his Ju-Jitsu. That was the end of our connection.”

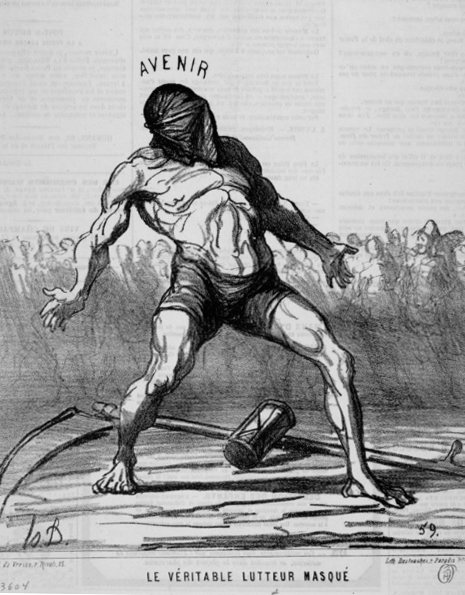

This split came at a bad time. The club was struggling. Enrollment fees and tuitions were considered to be too high by some, and the affluent classes of London were not lining up to apply. When the end finally came, the instructors scattered to the winds. Cherpillod, his already formidible skills enhanced with knowledge of Jujutsu, returned to Switzerland. Pierre Vigny left Shaftesbury Avenue to establish his own self-defense academy on Berner Street. The Jujutsuka also stayed in London, ultimately laying the foundation for a “European Jujutsu Boom”.

At any rate, Barton-Wright’s attention was focusing more and more on physical therapy. He continued to adapt and teach Bartitsu, but not with the same zeal or conviction. He began to bill himself as an Electro-Medical Specialist; and his collection of foot baths, ultraviolet lamps and thermophores continued to grow. By 1906, Shaftesbury Avenue was no longer advertised as a school of arms; it was the ‘Bartitsu Light Cure Institute Limited’.

In 1903, Sherlock Holmes retired to his bee farm in the Sussex Downs. His letters to Barton-Wright ended abruptly. Holmes’ interests from that point on seem to have shifted to chemistry, bee keeping and the compilation of his twin chef-d’oeuvres, “The Modern Forensic Sciences” and “The Complete Art of Deduction”.

And so ends Sherlock Holmes’ association with Jujitsu, Judo and Bartitsu.

Except for one private conversation in 1922.

As I have already told you, my grandfather was ‘The Old Man’, Sir Henry St. John Merrivale, 9th Baronet. He was a fascinating old beggar: a barrister, a Bachelor of Medicine, amateur prestidigitator, failed music hall comic, occult investigator, detective, anarchist and spy-master.

He was also a long-time member of the Diogenes Club and a good friend to Mr. Mycroft Holmes. It was through Mycroft, in 1905, that my grandfather was first introduced Sherlock Holmes, in the Stranger’s Room of the Diogenes.

They met several times thereafter, but the incident which now concerns us took place in December of 1922 at the Salmon & Gluckstein Tobacconist shop on Oxford Street.

Sir Henry had just popped in to buy a fistful of Dunhill panatelas when he noticed the elderly Sherlock Holmes standing between some tobacco bins. The Great Detective was making one of his rare visits to London. He had fled the coastal gales of East Sussex to spend Christmas with Mycroft in Pall Mall.

“I am afraid,” said Holmes, “that I have resumed that course of nicotine-poisoning which my good friend, Doctor John Watson, has so often and so justly condemned.”

My grandfather, as was his nature, demurred.

“A little vice never harmed a healthy man. You are far too vigorous as it is. Moderation is the key. Smoke a large pipeful and then go clear the lungs with a series of Baritsu kicks and rolls.”

“Bartitsu,” corrected Holmes.

“And yet your faithful friend and biographer, Doctor Watson, spelled it Baritsu in The Adventure of the Empty House.”

Holmes casually waved a hand in the air, as though brushing away a fly.

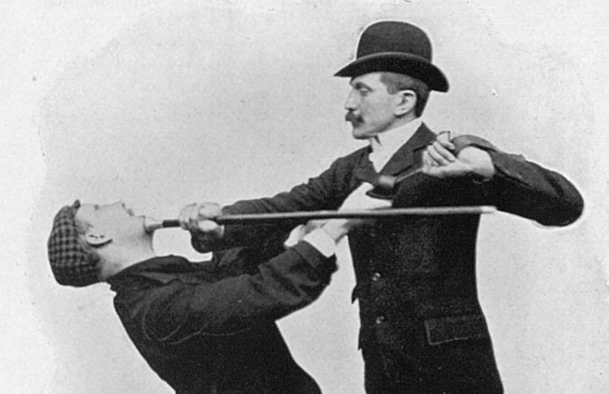

“Watson is a literary man”, he told my grandfather, ” and as such has little regard for the literal truth of his accounts. I have often had occasion to point out to him how superficial these are and to accuse him of pandering to popular taste instead of confining himself rigidly to facts and figures. Yet in this case I cannot judge him too harshly. Watson, knowing of my friendship with Mr. Barton-Wright and my membership in the Shaftesbury Avenue club, naturally assumed that I had utilized some sort of Bartitsu toss. Obviously, this was incorrect. Bartitsu did not exist in May of 1891, when my fatal encounter with Moriarty took place. Barton-Wright himself did not even begin to study Ju-jitsu until 1894; and his system of self-defense was not incorporated until 1898. It was my knowledge of Judo which proved so useful to me on the precipice of Reichenbachfall. Moriarty grabbed me in a front bearhug and I instinctively responded with an O Goshi hip throw.”

“But in all this time you saw no reason elucidate the mistake or to change the story so that Mr. Kano got the credit due to him for your survival?”

“Pshaw,” said Holmes. “The story itself was not harmed by such a minor error and, in fact, was probably ennobled by it. Everybody knows Kano’s name now. He values my friendship, but has little use for my kudos. On the other hand, Edward Barton-Wright’s reputation is in decline. This is most unfortunate. Bartitsu, as far as I am concerned, is the most effective street-fighting system I have yet encountered. Had I possessed such skills at that time, I would most likely have used them. Perhaps that one little word in Watson’s story of will yet spark a renewal of interest in his art.”

My grandfather persisted.

“But what of the spelling? Why Baritsu and not Bartitsu?”

Holmes laughed and lit his pipe.

“Bartitsu became Baritsu due to the bowdlerization of a printer, who suspected that this unusual word contained a double entendre involving mammaries. He solved the problem by dropping the initial t.”

I hope that solves more questions than it raises.

Michael Bertram Wooster

****

I am indebted to the Vernet Foundation, from which I drew the following material.

Russell, 1948/038/- Private letters and diaries

(Donor: M. Russell)

Kano, 1983/198/-

A collection of corresponance between Sherlock Holmes and Kano Jigoro. (Donor: D. Risei Kano)

Pike, 1954/053/-

Photocopies of 3 handwritten and unpublished diaries which cover 1887, 1891 and 1897. (Donor: Langdale Pike)

Trevor-Pitt, 1968/113/-

An archive of papers relating to Victor Trevor, including the typed transcript of a letter (dated June 1887) from William Sherlock Scott Holmes. (Donor: Amelia Trevor-Pitt)

Holmes, 1988/217/-

A collection of correspondence between William Sherlock Scott Holmes of London to Mr E. Wm. Barton-Wright in Kobe, Japan. (Donor: Mycroft Holmes)

Sheridan, 1947/042/-

(date 20 October 1900) from Edward Barton-Wright to Sherlock Holmes. (Donor: Audrey Ann Blake Sheridan)

An interview with Barton-Wright conducted by Gunji Koizumi. (Koizumi, G: “Facts and History”, Budokwai Bulletin, July 1950.)

The works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: A Study in Scarlet; The Sign of the Four;The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes; The Hound of the Baskervilles; The Valley of Fear; The Return of Sherlock Holmes; His Last Bow; The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes.