- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 11th October 2018

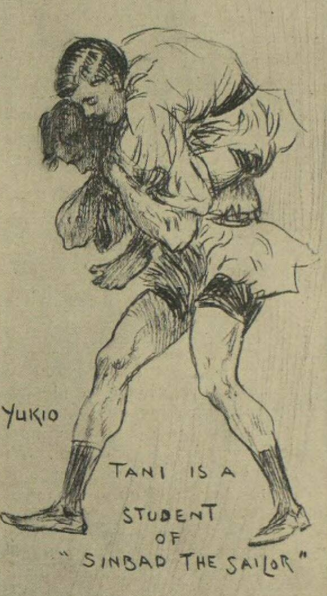

Mid-late 1901 was undoubtedly the heyday of the Bartitsu School of Arms, not least because it was during that period that the School’s champions were put to their greatest tests in public competition. Following a series of more-or-less academic displays and several novel style-vs-style challenge matches, both the sporting public and England’s combat champions were eager to see Bartitsu exponents pitted against “name” fighters.

It seems to have been widely accepted that sparring exhibitions of Bartitsu as a complete style – resembling a Dog Brothers gathering, in its combination of stickfighting, kickboxing and submission wrestling – would have been considered “brawling in a public place” under Edwardian English law.

Therefore, the next best option was to hold competitions in the various component styles. E.W. Barton-Wright was keen to oblige, proffering a series of open challenges via the pages of the Sporting Life, as was the custom then.

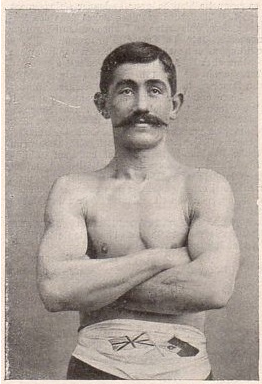

While the greatest controversy attended the exotic art of jiujitsu (and whether champions of that style would prevail against expert European wrestlers), Barton-Wright was also eager to locate a worthy boxer to challenge Pierre Vigny. Therefore, the following notification appeared in the Sporting Life of Wednesday, 10 July 1901:

Mr. E. W. Barton-Wright is anxious to find a good boxer who would willing to oppose one of his men for exhibition work to demonstrate the merits of English boxing against his system of boxing. No boxer under middle-weight need apply, as be that his man shall have no advantage in weight, therefore a heavy-weight would given the preference. Weight of his own man; 11 st. 4 lbs. Apply to the Bartitsu School of Arms and Physical Culture, 67b, Shaftesbury Avenue, W.C.

Barton-Wright’s curious mention of “his system of boxing”, rather than savate per se, was probably an oblique reference to the “secret style of boxing” that he had devised via collaboration with Vigny. It was likely also due to Barton-Wright’s ongoing reluctance to publicly align Bartitsu with French kickboxing.

The timing of the infamous October, 1899 Driscoll/Charlemont fight in Paris had been especially unfortunate from Barton-Wright’s point of view. The scandal resulting from that fight had generated massive ill-will against the French style among the English sporting public at exactly the time when he was attempting to introduce a “new art of self-defence” that incorporated French martial arts.

Thus, despite Vigny’s status as the Chief Instructor of the Bartitsu Club, Barton-Wright’s public pronouncements had tended to de-emphasise or even disparage savate per se, in favour of promoting their “new and improved” method of kickboxing that was unique to Bartitsu.

Within the week, Barton-Wright’s Sporting Life notice was answered by Professor Newton, a well-known boxing coach and partisan of the English style:

“Bartitsu vs. Boxing”: In answer to Mr. Barton-Wright’s challenge, which appeared the Sporting Life of the 10th last, Professor Newton, who is teacher of and firm believer in the British art of self-defence, has several pupils who have expressed their willingness to compete against Mr. Barton-Wright’s pupils at their respective weights in order to prove which is the better system. If a series of contests can be arranged, Mr. Barton-Wright will oblige by forwarding copy of his rules to the North London School of Arms and Physical Culture, 55, Barnsbury-road, London, N.

Unfortunately, but not uncommonly, nothing seems to have come of this proposed encounter. Beyond the formalities of public notifications in the newspapers, combat sports challenges were subject to behind-the-scenes negotiations and many never came to fruition, often due to personality clashes, logistical issues and/or disagreements over terms.

A short time later Vigny did, however, fight the boxer Jem Barry at a Bartitsu Club assault-at-arms event. As reported in the Sporting Life of November 25th:

Two minutes per round. Sharp work right and left. Barry knocked Vigny down after nearly getting the right on the jaw with sufficient force. Vigny got up and kicked right and left. Severe business.

Round 2. Sharp and severe work at close quarters. Both on ground twice, and toppled over in an embrace among the people.

Round 3. Barry led. Vigny had a rough time of it, and they frequently clinched. To the end, a splendid encounter. Vigny kicked and boxed hard. Barry punched with might and main. When time was called, honours were to the advantage of Barry on points.

The results of this hard-fought bout were not widely reported; another journalist said that the fight was inconclusive.

The next prominent boxer to publicly accept Barton-Wright’s challenge was none other than Jerry Driscoll himself. Shortly after the Vigny/Barry fight, Driscoll wrote the following letter to the editor of The Sportsman (a similar notice appeared in The Sporting Life on the same day):

Sir,—As an Englishman who has beaten the best Savate boxer, viz, feet and hands, against my hands only, I should be pleased to compete against Mr. Barton-Wright’s man, for from £50 aside, upwards, and largest parse. Match to come off early in January. I will also wager a good side bet that I stop Mr. Barton-Wright’s man inside ten rounds, Mr. Barton-Wright’s man to have his feet padded, the same as when he competed against Jim (sic) Barry. I only stipulate that we must have one English and one French judge, and the Sporting Life to appoint referee. No 30-second rounds, nor either man allowed to rest fifteen minutes, was the case when I met Charlemont.

Yours, etc., Jerry Driscoll (Instructor to the principal English amateur boxing clubs). Railway Cottage, Barnes.

Driscoll’s claim to have “beaten the best Savate boxer” would, itself, have been mildly controversial. Although Driscoll was widely held to have been handily winning the fight until his opponent landed a probably accidental, but definitely illegal groin kick, as a matter of record, Charles Charlemont had won that fight.

Driscoll shortly followed up with another letter:

Seeing Mr. Barton-Wright is on the warpath with his savate instructor, and matching him against our past boxers, I will box his Frenchman ten rounds for £100 aside, National Sporting Club’s rules, any time he chooses make a match. Money ready as soon as Mr Barton-Wright makes an appointment through the columns of the Sporting Life.

… and he raised the stakes again in The Sportsman of February 14th, 1902:

If Barton Wright wishes to match his Frenchman with me, and is not out for advertisement, he will attend the N.S.C. (National Sporting Club) at one o’clock on Saturday next. Vigny can have a match for £lOO or £3OO aside, and as the distance is but of one hundred yards, I hope that Mr. Wright will be on hand.

A similar notice from Driscoll was published in mid-April. On April 22nd, Vigny replied:

Pierre Vigny, Instructor of the Bartitsu School of Arms, is prepared to box Jerry Driscoll, in the English style, Queensberry Rules, if the National Sporting Club will offer a purse worth competing for. Jerry Driscoll has refused to take Vigny on in the French style.

Two days later:

In answer to Jerry Driscoll’s offer to wager up to £300 that he will beat Vigny in the match to be decided during Coronation Week, Pierre Vigny writes accepting the offer, and is also ready to find the backing for that amount, feeling confident that he will be able to defeat Driscoll inside ten rounds. It Driscoll will make an appointment with his backer the National Sporting Club, Vigny will be pleased meet him, and will be prepared to make the deposit at once.

Driscoll, on April 26th:

In answer to Pierre Vigny, Driscoll says that if Mr. Barton Wright will post £100 at the Sporting Life Office, his (Driscoll’s) backer will wager £300 to £100 that be beats Vigny inside ten rounds, under Queensberry Rules.

Two days later, Driscoll wrote again noting that his backer was then away on business, but that as soon as he returned, the money for the side-bet would be delivered to The Sportsman office.

Then, on the 29th of May, Barton-Wright re-entered the fray:

Mr. Barton-Wright has written calling attention to the fact that the authorities of a certain club, after offering a purse of £300 for a contest between (Vigny and Driscoll) to decide the merits of boxing versus savate and after getting the consent of both men to this arrangement, have suddenly withdrawn their original offer and now are prepared to give only £lOO. Although both men are most anxious to meet each other, naturally they do not intend engage in a serious contest of this kind without some real inducement. The training expenses would cost about £25, so that the loser would practically get his bare expenses paid be receiving 25 per cent of the purse. Mr. Barton-Wright would therefore be very glad to hear from anybody interested this matter, and who, perhaps with others, will be willing to assist in the financing of same, and so to make this match possible.

The Editor of The Sporting Life also quoted Barton-Wright to the effect that the proposed stakes of £100 were too low to represent the fighting worth of either Vigny or Driscoll, and at that point the proposed challenge seems to have fizzled out.

Ironically, the mysterious reduction of stakes by Driscoll’s backers – as well as Barton-Wright’s insistence that Vigny would not fight for less than a £300 stake – may have allowed the Bartitsu Club to dodge a public relations bullet.

Given his persistent efforts to distance Bartitsu from savate, and from the negative fallout of the 1899 Charlemont/Driscoll fight in particular, Driscoll’s challenges clearly put Barton-Wright in a very difficult PR position. Regardless of the outcome (and of the Bartitsu Club’s modifications to the techniques and rules of the French style), a Vigny vs. Driscoll fight would inevitably have been perceived as a “rematch” between savate and boxing. With feelings about the Charlemont/Driscoll fight still raw, English public sentiment would have been overwhelmingly in Jerry Driscoll’s favour, likely casting Vigny, Barton-Wright and Bartitsu as the unpatriotic villains.

Even worse, from Barton-Wright’s point of view, would have been the public perception that he and Vigny were symbolically aligned with Driscoll’s former opponent. In reality, there was seriously bad blood between the Bartitsu camp and the Charlemont camp. Barton-Wright had actually used the outcome of the Driscoll/Charlemont fight as ammunition during his acrimonious exchange of letters with Charlemont, thereby morally aligning himself and the Bartitsu Club with Driscoll.

Thus, if the Driscoll/Vigny fight had gone ahead, Barton-Wright would have been forced into an unenviable position. Even if Vigny had won against Driscoll, in the hyper-partisan social climate of the early 1900s, the “optics” would have been damaging for the Bartitsu School of Arms.

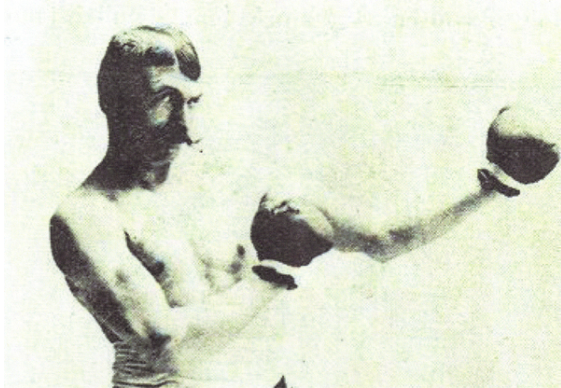

The Bartitsu Club continued to stage assault-at-arms displays in Nottingham, Oxford and other regional locations during early 1902. Ultimately, Vigny’s regular opponent on that tour was the jobbing heavyweight boxer Woolf Bendoff. Though Bendoff’s professional record wasn’t especially impressive, it’s likely that he represented a diplomatic compromise away from the politically fraught possibilities of Pierre Vigny taking on Jerry Driscoll.