Categories

- Academia

- Antagonistics

- Baritsu

- Bartitsu School of Arms

- Biography

- Boxing

- Canonical Bartitsu

- Documentary

- E. W. Barton-Wright

- Editorial

- Edwardiana

- Exhibitions

- Fencing

- Fiction

- Hooliganism

- Humour

- In Memoriam

- Instruction

- Interviews

- Jiujitsu

- Mysteries

- Physical Culture

- Pop-culture

- Reviews

- Savate

- Seminars

- Sherlock Holmes

- Sparring

- Suffrajitsu

- Uncategorized

- Video

- Vigny stick fighting

- Wrestling

Bartitsu at Home: Tommy Joe Moore Teaches Savate Hand Strikes

Posted in Instruction, Savate, Video

Comments Off on Bartitsu at Home: Tommy Joe Moore Teaches Savate Hand Strikes

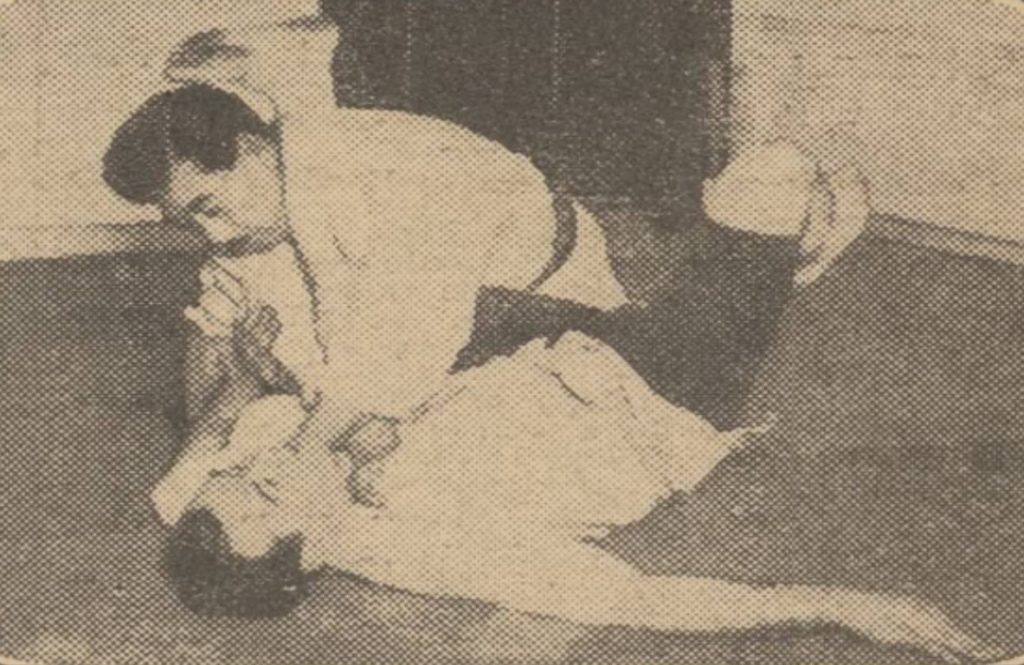

Yukio Tani in 1920

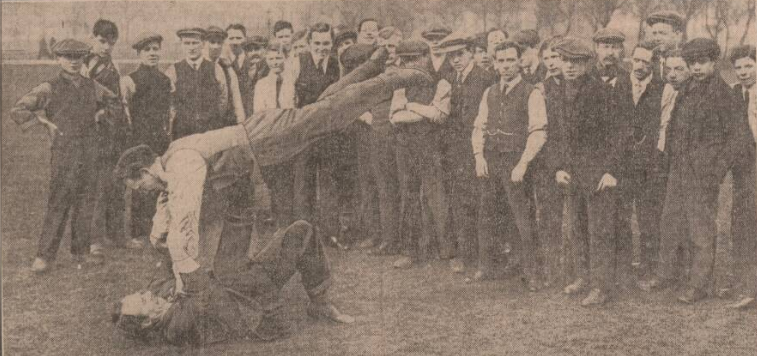

Former Bartitsu Club instructor Yuki Tani is shown executing a collar choke against wrestler Jack Madden in this photo from the Sunday Pictorial of January 4, 1920. Tani won the contest in a time of 14 minutes and 4 seconds.

Posted in Jiujitsu

Comments Off on Yukio Tani in 1920

Introduction to the Bartitsu Lab

In this short video, Bartitsu Lab founder Tommy Joe Moore introduces his approach to reviving E.W. Barton-Wright’s “New Art of Self Defence”.

We have long argued in favour of pressure-testing conclusions via hard sparring and endorse this approach as the best way forward for the Bartitsu revival as a whole. It’s well worth noting that the same, pragmatic methodology can and should be applied from the HEMA-oriented perspective of recreating the original art as closely as possible on its own terms.

Posted in Antagonistics, Video

Comments Off on Introduction to the Bartitsu Lab

Concerning the Bartitsu Compendium, Volumes 1 and 2

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 11th September 2018

By Tony Wolf

This article offers a brief “history” of the Bartitsu revival movement, especially via the production of the two volumes of the Bartitsu Compendium in 2005 and 2008.

The advent of the Internet during the late 1990s facilitated contact and communication in innumerable special interest fields, very often among individuals and small groups that had been working in relative isolation for years. The newfound ability to “meet” fellow enthusiasts from all around the world online dramatically expanded and accelerated many of these fields; it was, to put it mildly, a heady time.

In the martial arts sphere, the esoteric practice of reviving previously extinct fighting styles received an especially strong boost during this period. The Bartitsu revival began as part of this new movement, originally via the Bartitsu Forum Yahoo Group email list, which was founded by author and martial artist Will Thomas in 2002, almost exactly one century after the original London Bartitsu Club had closed down.

Within about three years, members of the international Forum – which had quickly and informally morphed into the Bartitsu Society – had tracked down a vast quantity of archival information related to E.W. Barton-Wright’s martial art. Most notable were Barton-Wright’s article series for Pearson’s Magazine, which had been discovered by the late British martial arts historian Richard Bowen and which were first broadcast online via the Electronic Journal of Martial Arts and Sciences website. Many of the characteristics of Bartitsu revivalism, including the concepts of “canonical” and “neo” Bartitsu and the essentially open-source nature of the revival itself, were likewise defined during this period.

By early 2004, we had so much information that it seemed fitting to try to get it into a publishable format, if only for the convenience of the (still) relatively few people who had taken a strong interest in the subject. Also, though, there was a growing sense that E.W. Barton-Wright had not yet received due recognition. The more we were learning about his life and fighting style, the more it seemed that he should be acknowledged as a martial arts pioneer and innovator. Therefore, the decision was made to dedicate any profits from the book to memorialising Barton-Wright’s legacy.

Because the potential readership seemed so small and specialised, we realised that the Bartitsu Compendium was unlikely to appeal to traditional publishers. Therefore, we decided to take advantage of the then-relatively new POD (Print On Demand) technology, which would allow individual copies of the book to be automatically printed and shipped as they were ordered.

Volume 1 of the Bartitsu Compendium – which was eventually subtitled “History and the Canonical Syllabus” – was compiled as a group labour of love. I volunteered to edit and generally steer the project and numerous others produced original articles, tracked down ever more obscure sources in European library archives and second-hand bookstores, manually transcribed print into electronic text (OCR technology was not then what it is now) and lent their talents to translations from various foreign languages (likewise re. translation software).

The compilation and editing process took about a year, and then the book was officially launched at a function held in an Edwardian-era meeting room in the St. Anne’s Church complex in Soho, London, literally a stone’s throw from the site of the original Bartitsu Club in Shaftesbury Avenue. A simple table display included a bouquet of flowers, a straw boater hat and a Vigny-style walking stick, along with print-outs of the various chapters. Ragtime music played quietly in the background.

I offered a short lecture on the history of Bartitsu and a demonstration of some of the canonical techniques, followed by a champagne toast to the memory of E.W. Barton-Wright. Guests were then invited to mingle and peruse the print-out chapters (and, if they wished, take them as souvenirs).

To our surprise, the first volume of the Compendium sold well and, in fact, it was Lulu Publications’ best-selling martial arts book for a number of years. Funds from those sales supported the first three Bartitsu School of Arms conferences (in London, Chicago and Newcastle, respectively) and paid for a Bartitsu/Barton-Wright memorial that became part of the Marylebone Library collection, among other projects.

The Bartitsu revival proceeded and grew, with increasing numbers of seminars and ongoing courses being established. By 2007 it was clear that we needed a second volume, presenting resources that went beyond the canonical material and into the corpus of material produced by Bartitsu Club instructors and their first generation of students.

Volume 2 was a more complicated undertaking because it involved cross-referencing over a dozen early 20th century self-defence manuals, almost all from within the direct Bartitsu Club lineage, with the aim of synthesising a complete neo-Bartitsu syllabus. Individual techniques were gathered from multiple sources and carefully assessed, omitting redundancies and duplications while retaining useful variations. We also wanted to avoid developing a fully standardised, prescriptive curriculum, in favour of allowing individuals and clubs to choose their own “paths” through the various techniques and styles that went into the Bartitsu cross-training mix. Further, the lessons of volume 2 were joined together by a set of technical and tactical principles or “themes” redacted from the writings of E.W. Barton-Wright.

Again, the production of the book was very much a team effort, requiring the locating, scanning, transcribing etc. of a wide range of antique self-defence books and articles.

The second volume of the Bartitsu Compendium (subtitled “Antagonistics”) was launched in 2008, and proved to be very nearly as popular as Volume 1. The Compendia have formed the backbone of the Bartitsu revival since then, especially during the “boom time” of roughly 2009-13, which was engendered by the massive popular success of the action-packed Sherlock Holmes movies and consequently by substantial media, pop-culture and academic interest in Bartitsu.

There are currently about 50 Bartitsu clubs and study groups spread throughout the world and many of the old Bartitsu mysteries have either been solved outright or satisfactorily mitigated through educated guesswork. Although it will never be the “next big thing” in the martial arts world, all signs point to Bartitsu continuing as a niche-interest study for those who spend about equal time in the library and in the dojo.

Posted in Editorial

Comments Off on Concerning the Bartitsu Compendium, Volumes 1 and 2

Miss Blanche Whitney, the World’s Champion Lady Wrestler (1911)

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Saturday, 26th November 2016

This gallery of images from an article in the Oregon Daily Journal (April 30, 1911) showcases the combative talents of Miss Blanche Whitney.

Between 1908-11, the Philadelphian Miss Whitney travelled the US carnival and vaudeville circuit, taking on all comers as the “World’s Champion Lady Wrestler”. She challenged any woman in the audience to try their skill against hers, and would also grapple with any male wrestler weighing no more than 145 lbs (she herself weighed in at a muscular 155 lbs). She was also held to be a proficient boxer and foil fencer, and indeed an all-around athlete whose skills included bowling and gymnastics.

During April of 1910 she defied a police ban on “lady wrestling” contests in Chicago and took on Miss Belle Myers in an otherwise all-male wrestling card. She then moved on to performing tent-shows at the lakeside White City amusement park, where she proudly informed an interviewer that she was teaching up to four classes a day for “society ladies” desiring to learn how to apply half-nelsons and hammerlocks.

It may have been at the White City that she assembled her troupe of “Lady Athletes” – wrestlers, boxers, ball-punchers and gymnasts – with whom she later toured to perform at the great Appalachian Exhibition.

The “Americanised jiujitsu” featured in these pictures may not be strictly traditional – it may, in fact, represent something more in the nature of catch-as-catch-can wrestling plus a couple of half-learned tricks from a jiujitsu manual. Nevertheless, while Miss Whitney was self-professedly not a suffragette (“I can take care of myself without a vote”), she had no qualms about promoting her contests and classes as exemplars of women’s self-defence.

If a husband is cross and disagreeable, “advises the stalwart Miss Whitney, “just put him on his back as fast as he can get up. It will make a gentle man out of him in no time.

This clinging vine stuff is alright, but, believe me, the woman is a winner who can look her husband in the eye and say, ‘what about the coin for that new dress? Do you come across like a little man, or do I throw you down and sit on you while you make up your mind?’

Think how different the world would be if such scenes were common. The stranglehold might be useful in case hubby came home late at night.

Miss Whitney reported that she herself had applied some of these lessons one night in a Chicago alley:

(…) a tall man halted her in the semi-darkness and said something which, in her surprise, she took to be the words of a “hold up. ” Whether it meant robbery or flirtation, she didn’t waste time inquiring. She merely gripped him by the coat lapel, the simplest trick in Americanized jujitsu, and yanked him forward and downward . At the same instant she swung a clenched fist upward – the simplest blow in sparring – and landed on his jaw. The combination of descending head and ascending fist came within an ace of being a knockout. Her accoster reeled, dazed, for the instant she needed to brush past him and reach the full streetlights.

Posted in Antagonistics, Wrestling

Comments Off on Miss Blanche Whitney, the World’s Champion Lady Wrestler (1911)

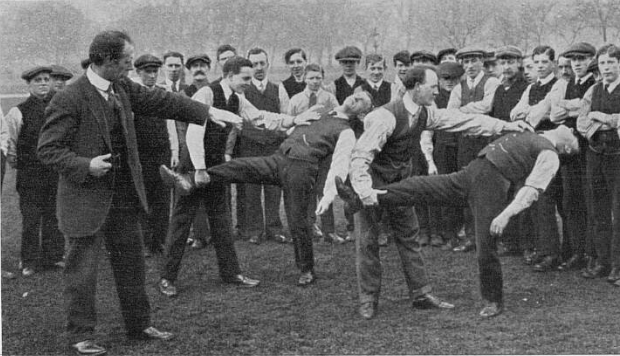

“Engaging Toughs”: Pressure Testing and Sparring in Neo-Bartitsu Training

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Monday, 2nd September 2013

“I learned various methods including boxing, wrestling, fencing, savate and the use of the stiletto under recognised masters, and by engaging toughs I trained myself until I was satisfied in practical application.”

– E.W. Barton-Wright, 1950

The Bartitsu revival has gathered real momentum over the past several years, spurred on by the success of the Sherlock Holmes film franchise and by the continuing popularity of steampunk. New clubs and study groups are forming and Bartitsu presentations have become fixtures on the pop-culture convention circuit, especially at steampunk conventions.

The association with Sherlock Holmes and “fantastic Victoriana” means that Bartitsu now holds some appeal for people who might not otherwise take much of an interest in martial arts training, perhaps via taking a “taster” class or just watching a demonstration at a convention. Thus, their first exposure to Bartitsu is often in a basically ironic, playful or academic context that is geared towards people with no, or very little, prior background in martial arts training.

Going through the motions …

Under these circumstances, the overriding requirements are that the experience should be safe and enjoyable for all concerned. Thus, in taster classes, techniques are typically taught and rehearsed slowly and carefully, with some attention to correct form but little emphasis on realistic application against a determined, resistant opponent.

Demonstrations at these events can vary widely, from closely researched presentations of authentic Bartitsu techniques, through to slapstick displays that bear little actual resemblance to the c1900 art.

Engaging toughs …

Participants in an ongoing Bartitsu course, however, can expect to go beyond the rote rehearsal of pre-arranged techniques, and to be progressively introduced to the crucial element of spontaneous, active resistance. In so doing, they may join in the spirit of E.W. Barton-Wright and Pierre Vigny “engaging toughs”, or Bartitsu Club jujitsu instructors Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi, who regularly took on all challengers on the stages of London music halls.

The cliched “sport vs. street” or “sport vs. martial art” argument posits an artificial either/or duality between self-defence/combat training and active competition. Understanding that it’s impossible to safely spar or compete using the totality of techniques from a combat-oriented style, it certainly is possible to spar within a rule-set that draws as much as is safely practical from that style.

It can easily be argued that the benefits of actually being able to test those techniques – as well as, more generally but also importantly, fighting attributes such as endurance, courage and the ability to improvise under pressure – against active resistance out-weigh the objection that one is only using a limited range of techniques.

The case can also be made that it is in the crucible of athletic pressure-testing, via hard sparring or any other form of spontaneous, genuinely resistant training, that the art initiated by Barton-Wright in the late 1890s is really brought back to life.

Posted in Sparring

Comments Off on “Engaging Toughs”: Pressure Testing and Sparring in Neo-Bartitsu Training

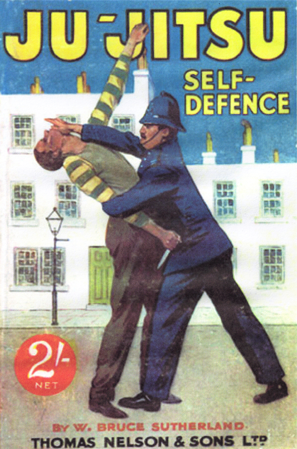

W. Bruce Sutherland Teaches Jiujitsu in WW1-era Edinburgh

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Tuesday, 3rd January 2017

Along with Percy Longhurst and William and Edith Garrud, W. Bruce Sutherland was one of the most prominent members of the “second generation” of British self-defence experts. A Scotsman, Sutherland ran a physical culture academy in Edinburgh and took up jiujitsu after losing a wrestling challenge match to former Bartitsu Club instructor Yukio Tani.

Sutherland’s book Ju-Jitsu Self-Defence went through a number of editions and was notable for its inclusion of a number of “third party” defence and restraint techniques, designed for use by police constables.

By 1915 W. Bruce Sutherland was well-established as a self-defence and close-quarters combat specialist in Scotland, and the ongoing war effort saw him teaching the basics of jiujitsu – according to his own system – for institutions as diverse as the Boy Scouts, the Army and the Special Constabulary.

Posted in Jiujitsu

Comments Off on W. Bruce Sutherland Teaches Jiujitsu in WW1-era Edinburgh

A Letter by Pierre Vigny Sheds New Light on an Old Feud

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Friday, 17th August 2018

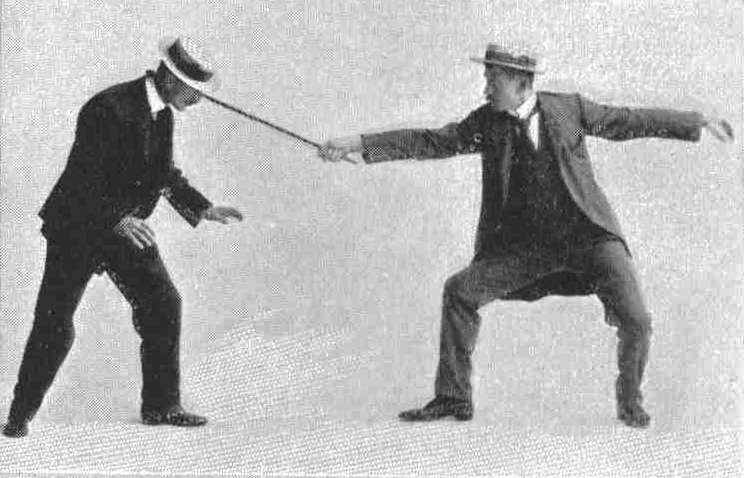

A newly-discovered letter written by Pierre Vigny illuminates both the style of savate he taught at the Bartitsu Club and his feud with Parisian savateur Charles Charlemont. Although Vigny was a prominent professor of antagonistics and was quite widely quoted via articles and interviews, this letter represents one of the very few known instances of his direct commentary.

In early October of 1901, Charlemont wrote a letter objecting to Vigny being promoted as the “champion in French boxing and single-stick” in connection with Bartitsu events. In this letter, which was published in several English newspapers, Charlemont asserted that Vigny had lost to Charlemont himself, M. Mainguet (then an assistant at Charlemont’s school) and “other boxers in Paris.” Charlemont closed by suggesting that Vigny was a “bluffer” who was trying to make a name for himself as a self defence teacher in London.

E.W. Barton-Wright, who was Pierre Vigny’s employer at the time, replied that Vigny saw Charlemont as being a “fantastic dancer only, without the slightest right to the title he has assumed” and noted that Vigny’s championship claim vis-a-vis stick fighting was specific to his own style. Barton-Wright then offered to financially back Vigny in two “World Championship” contests with Charlemont, the first being straight French kickboxing and the second in which Charlemont could kick and punch, but Vigny would restrict himself to boxing.

Barton-Wright further noted that if Charlemont did not accept the challenge, he (B-W) would “allow Vigny to go to Paris and publicly horse-whip him”, before closing with a few choice remarks about the then-recent and infamous Charlemont/Jack Driscoll savate vs. boxing contest (which had ended in a very controversial win to Charlemont).

Despite an exceptionally heated exchange of letters to the editor, the various parties couldn’t agree on terms and so the proposed Vigny/Charlemont challenge fight never happened. Their dispute was, however, illustrative of a wider controversy within the world of French kickboxing.

As we have frequently noted in the past, the academic, touch-contact style promoted by the Charlemonts was coming under increasing criticism at the turn of the 20th century. On October 13th, 1900, Pierre Vigny’s comments in the following letter to Frank Reichel, then Secretary of the French National Sports Committee, were published in the journal La Constitutionelle. They confirm our theory that Vigny was a member of the minority camp, arguing for a radical reform of French kickboxing:

(…) As for the way of organizing this World Championship, why do we not agree upon the rules in force in England, namely: a number of completed rounds, for example six bouts of three minutes each, one of which is a minute of rest, during which the jury, taken naturally from among the most competent, would make notes upon the hits and the work by each opponent in each resumption.

If one of the two opponents is not out of the fight before the end of the sixth resumption, the jury will declare the one who has the most points to his credit to be the winner, or if the two champions are found to be “ex-œquo” (“in an equal state”), they will decide a new meeting.

A good reform would be to remove, in this championship, the announcement of touches; if it is necessary to announce that one has been touched on the shin (which is one of the most frequent strikes), we lose, by the slight pauses resulting from those announcements, whole combinations; it prevents those interesting and scientific passes that may follow.

These rules are those of my boxing and savate school which I introduced in London and which is a branch of what Mr. Barton-Wright, the well-known initiator of the new method of personal defense , calls ‘Bartitsu’.

The editor of La Constitutionelle agreed with Vigny, adding that:

We never say anything else: French boxing is full of inertia and nonsense. It is worthy of derision for one to stop on receiving a light stroke, crying “touché!”, when, in reality, one would “reply” thoroughly. By not going beyond these conventions, we have made French boxing a superb exercise in flexibility, but that is all. From the truly combative point of view, it is especially practical on an ignorant opponent, or perhaps a passing drunkard.

A fighter who “replies” bravely removes the effect of the cross-over and turning kicks; cancels all this virtuosity, all this affected elegance.

French boxing lacks strong punches. The punch of the Joinville style does not land heavily upon the body.

The victory over Driscool (sic – Driscoll) is not an affirmation of the French method; it is a proof of the high personal worth of Charlemont, of his fine courage, his temperament and his dash.

What is needed is a rational method, less elegant and more useful.

Some further context may be useful. In a follow-up letter to the editor in December, Barton-Wright reported that Charlemont had by then refused the challenge because “he says he is not a pugilist, but a Professor of Savate”. Barton-Wright also claimed that it had actually been Pierre Vigny’s brother who had lost the bouts referred to in Charlemont’s original letter, and closed with some very disparaging remarks about Charlemont’s character.

This issue is confused by the facts that Pierre Vigny evidently had at least one brother, named Eugene, and possibly another, named Paul, and that when the newspapers referred to “Professor Vigny of Geneva” they did not always specify which Vigny brother had actually fought. It is certain that, on March 11, 1897, one of the Vigny brothers lost conclusively in a boxing match against an English boxer named Attfield, and was then defeated in a savate match against Charles Charlemont. It may also be notable that Pierre Vigny initially travelled to England to improve his boxing, before joining forces with Barton-Wright.

Addressing Vigny’s point re. shin kicks; the reliable efficacy of those techniques had been in serious question since the aforementioned Charlemont/Driscoll debacle a few years earlier. Many French observers were startled when Charlemont’s low-line kicks didn’t have the presumed devastating effect upon Driscoll, who was able to evade or simply ignore most of them, while dealing considerable damage with his gloved fists.

The rules of that bout, which were very close to those Vigny himself later instituted via the Bartitsu Club, represented a radical departure from the Charlemonts’ favoured style of French kickboxing. Vigny’s larger point, though, does not advocate a reformation of technique so much as of protocols.

Following the convention of academic fencing, the Charlemonts’ style required the formal courtesy of calling “touché!” at even the lightest touch of the opponent’s fist or foot. This had the effect of rewarding speed and dexterity, but at the cost of complexity and realism, given that it essentially paused the bout, artificially requiring both fighters to acknowledge the point, then re-set and start again.

One experienced witness to the Charlemont/Driscoll fight noted that Charlemont was handicapped by his long experience of kicking lightly in academic bouts, to the extent that those low kicks that did land lacked stopping power. Parsing the entire range of eyewitness reports on that fight, from both French and foreign observers, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusions that Charlemont would have lost if not for an accidental but strictly illegal kick to Driscoll’s groin, and that he certainly shouldn’t have been awarded the victory because of it.

The argument over academic touch-contact vs. professional full-contact continued in French kickboxing circles until the outbreak of the First World War, which had a devastating effect on the sport. Many young fighters naturally served as soldiers during that awful conflict, and many were badly wounded or killed. Hubert Desruelles, who appears to have at least occasionally taught at the Bartitsu Club as well as at his own schools in France, was severely injured in both arms during the war, putting an end to his athletic career.

During the post-War decades, French kickboxing slowly rebuilt itself to include both the traditional “touch” (assaut) style and a full-contact style influenced by the no-nonsense ethos of British and American boxing. If only a similar compromise could have been reached circa 1900 …

Posted in Savate

Comments Off on A Letter by Pierre Vigny Sheds New Light on an Old Feud

By Hook or By Crook: A New Weapon for the Millwall Dock Police (1903-05)

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Monday, 30th October 2017

During the first decade of the 20th century, the Millwall Dock area of London’s East End was a notoriously attractive target for all manner of plunderers, who found easy entrance and escape via the Dock’s complex, shifting maze of alleyways. The Millwall Dock Police, all of whom were former soldiers and whose average height was an impressive 5’11”, frequently found themselves in hot pursuit of agile thieves and looters on foot.

In December of 1903, the Chief Constable of the Dock Police introduced a unique weapon to assist his constables in making arrests of runaway thieves. This new item was a sturdy staff of 1″ oak with a wide curved handle, very similar to a shepherd’s crook. As well as proving useful as a general-purpose walking stick, the staff was ideally suited to catching fleeing felons by snaring them around the neck, arm, leg or ankle.

The Chief Constable devised training drills for his men in the use of the hooked staff, “introducing several cuts and guards which are, at present, little known”, according to a report in the Nottingham Evening Post.

In an editorial, a journalist for the West Somerset Free Press remarked that the new weapon seemed to have been designed on the “Japanese self-defence principle”. That comment was very likely intended as a general allusion to jiujitsu but it also, probably accidentally, evokes the use of specialised “mancatcher” weapons such as the sodegarami, tsukubō, and sasumata * in ko-ryu martial arts, most especially those associated with police work in feudal Japan.

The same journalist struck a pragmatic note of caution, observing that “there is considerable danger attached to the use of such weapons (…) for a man tripped up by a crooked stick might easily sustain severe injuries, and to maim prisoners is, to say the least of it, not consistent with English use.”

Nevertheless, by 1905 the crook-staff had become standard issue for Millwall Dock police constables. Very similar techniques were likewise advocated for civilian use by E.W. Barton-Wright and Pierre and Marguerite Vigny, all of whom promoted the use of crook-handled canes and umbrellas to trip and otherwise impede attackers:

* A modification of the sasumata has, incidentally, been revived in recent decades and is now widely used by Japanese police, security officers and even teachers; the latter regularly train in the use of the sasumata against knife-wielding school invaders.

Posted in Antagonistics

Comments Off on By Hook or By Crook: A New Weapon for the Millwall Dock Police (1903-05)

“The Quarter-Staff Then and Now” (1934)

- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 14th March 2019

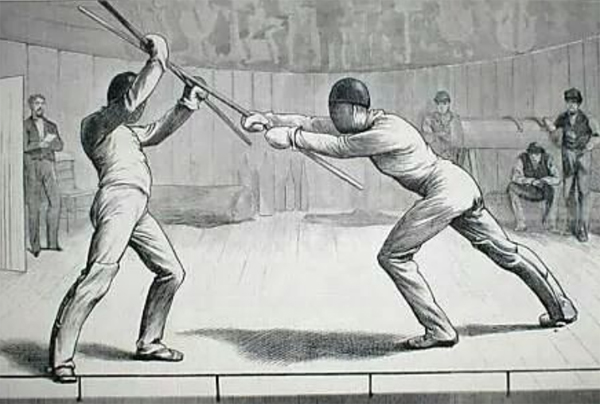

The “last hurrah” of the venerable English tradition of quarterstaff fighting took place on the gladiatorial stages of the early 18th century, when professional roughhousers such as James Figg “took on all comers” with various weapons for the chance to win prize money. As the sport of boxing overtook weaponed stage-fighting, the quarterstaff largely receded into folklore, aside from sporadic and largely undocumented revivals via rural fairs.

During the mid-late 19th century, however, the confluence of newly-devised protective equipment for sports such as cricket and fencing and the renewed enthusiasm for the tales of Robin Hood laid the basis for a widespread quarterstaff fencing renaissance.

From the 1870s onwards, the old/new sport became particularly popular among soldiers and was frequently a highlight of “assault-at-arms” exhibitions, featuring displays of martial gymnastics and all manner of antagonistics. Two instructional manuals were produced – Thomas McCarthy’s Quarterstaff: A Practical Manual (1883) and a chapter in R.G. Allanson-Winn’s comprehensive Broadsword and Singlestick (1898).

Bartitsu founder E.W. Barton-Wright claimed that he had often had to defend himself against attackers armed with quarterstaves – among an alarming variety of other weapons – during his travels abroad. It’s likely that he was referring to his time working in mining settlements in Portugal, where the folk-sport/martial art of jogo do pau was widely practiced during the late 19th century, though the matter of why he may have been repeatedly attacked there remains open to speculation. In any case, according to Barton-Wright’s own reports, his favoured tactic of closing in against opponents armed with superior weapons – notably a feature of his presentations of the Vigny method of stick fighting – was inspired by these encounters.

In England, quarterstaff fencing exhibitions persisted well into the 20th century, sometimes incorporating crowd-pleasing “stunt” elements, which had been disparaged by Thomas McCarthy as “made-up affairs, just for show”. Interestingly, a number of late-19th century reports on quarterstaff matches refer to disarmed combatants immediately shifting to boxing – though it’s difficult to say to what extent this may also have been tongue-in-cheek showmanship for the crowd.

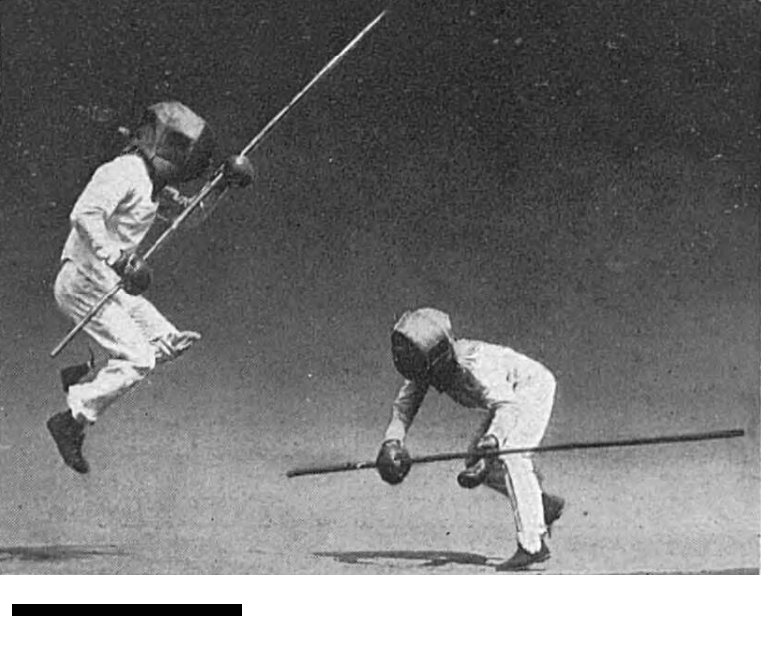

This rare snippet of film from a 1925 military display in Portsmouth features a moment from a particularly “showy” bout with staves, reminiscent of professional wrestling:

“Look, what’s that up there?!” An old trick given a new twist.

The Boy Scouts also took to quarterstaff fencing and, for a brief period, it was listed alongside singlestick play, boxing, foil fencing, wrestling and even jiujitsu as accomplishments required to achieve the Master-at-Arms badge. The Scouts also produced their own, simplified manuals for the instruction of young staff fencers.

The following, newly-discovered pictures represent a fairly late addition to the corpus of English quarterstaff fencing materials. They originally appeared in an Illustrated London News article titled “The Quarterstaff: Then and Now”(1934). The photos were taken at the Royal Air Force Depot in Oxbridge, and feature R.A.F. swordsmen Sergeant Turner and Sergeant Jarrold, “refereed” by Professor Ware. Note that, although Turner and Jarrold are shown here in regular gym kit for purposes of demonstration, during competitive staff play they would have worn protective equipment of the type shown above. The captions are by M. Pollock Smith.

Posted in Antagonistics

Comments Off on “The Quarter-Staff Then and Now” (1934)