- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Thursday, 6th December 2018

This self-defence article by the Icelandic wrestler and showman Johannes Josefsson was published in the Sydney Sun newspaper on June 9th, 1911.

Readers familiar with the basics of both jiujitsu and glima may well wonder at a number of Mr. Josefsson’s techniques, which seem to bear a far greater affinity to the former than to the latter.

During recent years public interest in any and every really valuable form of self-defence has increased very largely, and on that account it will be a matter of the greatest surprise to me if the true merits of “Glima,” the particular form of self-defence that has actually been practised in Iceland for nearly one thousand years, do not, when once known, become generally recognlsed, for, as has been proved on countless occasions, it is at once the simplest and yet withal the most efficacious of all exercises.

But as to the present time, the ancient pastime of my countrymen has been jealously guarded from all foreigners. Indeed, the only occasion when strangers were allowed to witness it during the whole of the last century was when it was displayed before King Christian IX of Denmark at Thing-vellir, when he visited Iceland in 1874, and even then only two men took part — the presont Rev. Sigurour Gunnarsson, of Stykkisholm, and the Rev. Larus Halldorsson, of Reykjavik.

But times change, and thus to-day, even in far-away Iceland, where news from the outside world is slow to creep in, we have at last recognised that no good purpose is being served by still keeping secret our ancient form of self-defence, the knowledge of which, valuable though it is in everyday life, must necessarily play “second fiddle” in scientific warfare. On that account, therefore, to-day I feel no qualms in divulging to readers the secrets of this form of self-defence, which has been practised In Iceland since 1100, when my country was a Republic. It was not then limited to the platform nor to any special occasion, for throughout the land, from the country, farm to the Althing (Parliament), it was a daily exercise in which most men took part.

Tho essential idea of this Icelandic form of self-defence is to enable the weaker to hold their own with the stronger, and I am not exaggerating when I say that. If she will take the trouble to learn some of the tricks and “hitches” of Glima, even a woman possessed of only ordinary strength will be able to defend yourself against, and overcome, an opponent possessed of far greater physical strength.

In recent years, too, the perfection to which Glima has been brought has proved it to be, in a very high degree, an exercise which gives health and endurance to the body, and which also acts as a real source of refreshment to tho mind, while, at the same time, sharpening the courage, smartness, and intellect of those who take part in it. I would mention that most of the grips are formed by the aid of the feet and legs, so that, even should an exponent of Glima have his or her hands tied, a capable resistance can still be made, n0 matter from which side the attacker may decide to start

operations.

It would be easy to write at considerable length about the history of this wonderful form of self-defence, for the story of how, little by little, new holds and hitches have been thought out to enable its exponents to be prepared for all emergencies is full of interest. Still, in the space allowed to me, I could not do sufficient justice to the subject, so I will content myself by explaining various tricks which are likely to prove most useful in cases of emergency in everyday life. Even in these civilised days, the hooligan and larrikin is far from “a back number,” as cases so frequently reported in the press clearly prove, but I would dare swear that these amiably-inclined “gentlemen” would speedily havo cause to regret their temerity if they were to attempt an assault on an opponent conversant with Glima.

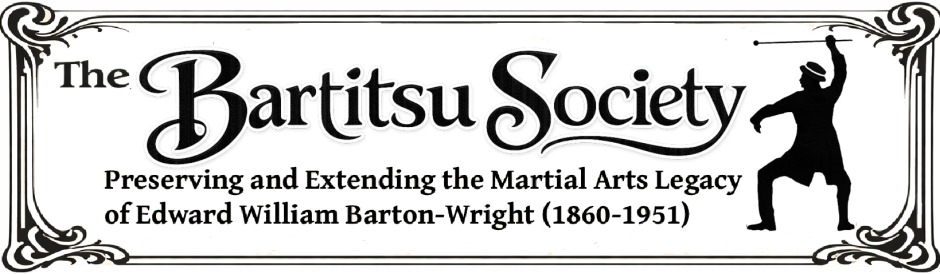

Perhaps the most common form of attack is with the fists, and, generally speaking, a man posssessed of some knowledge of how to box must inevitably have a great pull over an opponent who has never learnt how to use his fists. I will, therefore, explain how an attack with the fists can be easily warded off, and also how the attacker can be reduced to a state of lamb-like passivity.

For the sake of example, let us say that he leads off with the left, as shown in the accompanying illustration. As he strikes out, all that it is necessary to do is to throw yourself down on your left hand, at the same time throwing the right foot across his right leg just above the knee, and quickly gripping your left foot behind and over the opponent’s right, when, by pressing your right foot back and your left foot forward, you have him in such a position that you can throw him to the ground, and, by exertlng pressure, keep him there until he has decided that further attack would be, to put it mildly, a most indiscreet undertaking.

On paper, no doubt, this explanation may not seem quite clear, but if you will practise the hold for a minute or two with any opponent you will be able to prove its value at once. But I do not think I need give any clearer example of the merits of this trick than by saying that, although I am not a boxer myself, I am, nevertheless, prepared to challenge even the champion of the world, and to throw him to the ground before he can make any real use of his fistic ability.

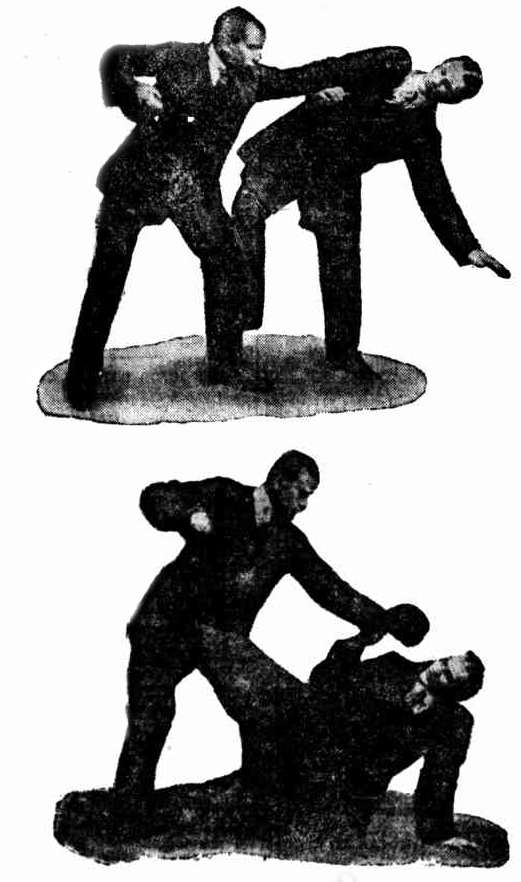

When unarmed, to be attacked by an opponent with a knife is a happening which even Mark Tapley would assuredly not have found particularly cheering. However, such an attack can be rendered completely ineffective, as follows. Let us suppose that the attacker strlkes out with his knife in

the right hand. As he does so, the attacked must move slightly to the left, so that the arm comes over his shoulder.

He must then turn quickly to the right, at the same time twisting his left leg round the attacker’s right, as shown above, and also pulling the attacker’s right arm across his chest, when the former will find himself in a position from which he cannot possibly extricate himself, for, by putting on even slight pressure, his opponent can break either his arm or his leg with the greatest of ease.

Maybe, in explaining what can be done, I must seem rather a bloodthirsty person. As a matter of fact, however, I should like to say that I am the most peacefully-inclined individual in the world. Still, to show how Glima can he made of real value in everyday life in the case of attack, it is necessary to point out the unenviable position any opponent must find himself in if he

struggles against a Glima “hold.”

An excellent means of throwing an opponent off his balance is known in the Icelandic form of self-defence as the “inverted hitch.” This is performed with either right foot on right (as shown above) or left on left, by hooking the foot slantwise round an opponent’s heel, the attacker’s knee bent slightly forward and his opponent’s slightly inward, so that the foot is locked in the position shown in the illustration. The attacker then draws his foot smartly to one side, and with his hands he keeps his opponent from jumping, for it is important to keep him down, otherwise the trick can be frustrated.

Another valuable trick for unbalancing an opponent is the “leg trick.” This is performed by placing the right foot on the opponent’s foot, or vice versa, so that the inner part of the foot touches the outer part of his foot. The feet are then drawn from him, and the hands used to complete the fall.

I would mention, by the way, that the last two tricks I have described will be found particularly effective should any reader encounter some individual in a crowd, or elsewhere, who shows some inclination to assert his position in an unploasnnt manner by jostling or otherwise using undue pressure. Yes, the “leg trick” and “inverted hitch” will be found invaluable replies to a jostler’s idiosyncrasies.

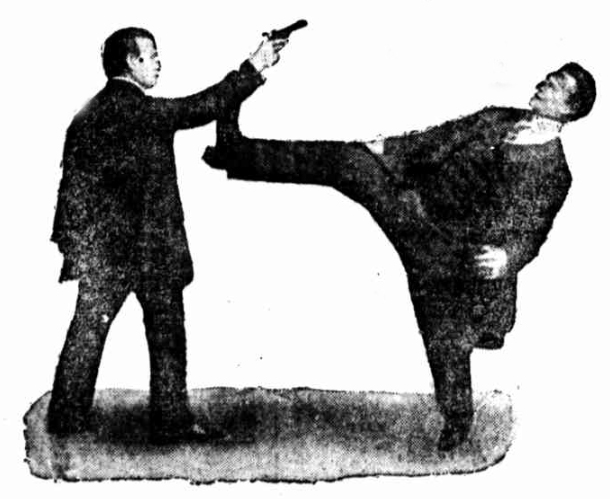

An opponent possessed of “firearms” and unamiable inclinations is never a particularly pleasant person to meet. Still, at close quarters it is possible to deprive him of much of his advantage if you will act quickly, and act as follows: —

Let us suppose that he is trying to extort money or the fulfilment of some wish by levelling a revolver at your head, and threatening “your money or your life” unless you consent to his dictates. As he raises the revolver step quickly back, at the same time leaning backwards, and with your right foot kick up his wrist in such a way that his aim is completely “put out of joint,” in that, whether he fires or not, the shot must inevitably miss its destination.

I do not pretend, of course, that this trick is in any way infallible, for an opponent with firearms and his finger on the trigger must necessarily be possessed of an enormous advantage over an unarmed adversary. At the same time, with sufficient practice, the simple device I have explained can be performed so rapidly that, while the arm is being raised to fire, the foot acts more quickly, and reaches the wrist before the revolver is in the requisite position to make an effective effort.

Another extremely useful way of disarming an opponent— if only you are quick enough — is shown here. As the attacker levels his revolver at his adversary’s head, the latter quickly bends down and grasps his opponent’s right wrist with his left hand and the latter’s left with his right hand, the while forcing his left wrist back. With his right leg he then encircles the attacker’s left in such a way that he can easily throw him backwards, when, by gripping the wrist of the hand In which he holds the revolver, and by pressing the thumb on the back of the armed hand and gripping his palm with the other fingers, an opponent is inevitably forced to drop the revolver.

Try this grip on anyone you like, no matter how strong he may be, and you will find it extraordinarily effective.

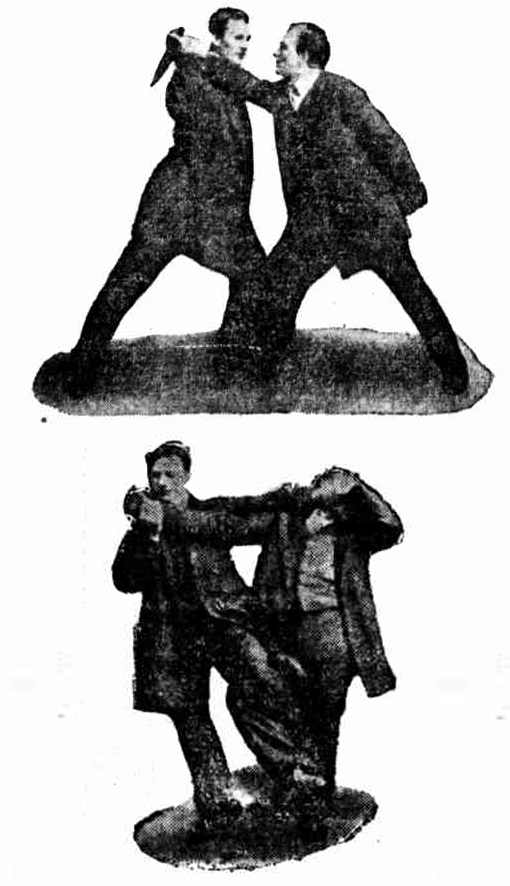

A trick I would earnestly commend to ladies is known in Glima as the “zig-zag trick”. By this manoeuvre, even a child can throw a strong man to the ground with lightning rapidity, and in my native country I have often seen a little Icelander bring about the overthrow of a man who, in a hand-to-hand struggle, would probably have defeated her “with two fingers.” The requisite position in which to bring this trick into play can be understood at once by glancing at the illustration.

The “zig-zag trick” is “laid” by placing the right foot round an opponent’s right leg, when, by quickly gripping him by the wrists and swinging him slightly to the left, he will find himself on his back in a fraction of a second. The valuo of this trick is derived entirely from the laws of balance, and, if practised a few times, ladies will find it particularly useful as a means of subjugating someone much stronger than themselves.

The “gentle hooligan” who relics upon a knife or dagger to bring about an opponent’s downfall can he subdued as follows. As he strikes downwards with his knife, the person attacked bends slightly backwards, at the same time gripping the right wrist with the left hand and his right ankle with the right hand from the outside, when, by pressing the leg upwards, as shown in the illustration, an opponent, no matter how strong he may be, can be thrown backwards to the ground.

I quite realise that “the hypercritical reader,” who, maybe, has never even heard of Glima, will probably scoff at the tricks I have explained, by reason of the fact that in cold, hard print they probably sound far from easy of accomplishment. I would hasten to say, therefore, that every Glima trick explained in this article will be found perfectly simple after a little practice. After all, it is on practice, and practice alone, that each and every form of self-defence depends for its real value in times of stress; and when I point out that a really clever exponent of Glima is more than a master for an adept at any other form of self-defence, I am merely giving this Icelandic pastime the credit to which it is entitled.

In conclusion, I would lay special stress on the necessity of each trick being performed sharply and decisively. Had space permitted I could have explained many other tricks which might possibly have come in useful at some time or another to readers. If, however, they will be content to thoroughly master the various “self-defence” exercises set forth in this article, they will find that they are armed with a stock-in-trade of defensive tactics which will assuredly serve them is good stead should necessity to bring them into play arise.

No speclal gymnasium is required in which to practice Glima tricks; any ordlnary-sized apartment will serve the purpose. In fact, a plot of level ground anywhere furnishes an excellent school, providing there are no stones.

I would mention, too, that no carpet is required, and the tricks may be practised in ordinary clothes, though, until they become fairly expert, I would counsel beginners not to wear too-heavily-soled boots or shoes; soft shoes, or the stockinged feet, are best when commencing to practise Glima tricks, as – speed being so essential to their successful accomplishment – unnecessarily hard knocks are sometimes given when heavy footwear is worn.