Clubs are generally collaborative efforts between Bartitsu enthusiasts who are experienced in one or several of the styles that went into the original “Bartitsu blend”, or in similar martial arts/combat sports. Some clubs are led by one or more experienced martial artists with diverse training and teaching backgrounds. Clubs may enjoy the practice of Bartitsu towards historical recreation, athletic competition and/or as self defence training.

The consensus within the Bartitsu Society is that in order to stay within the “umbrella” of Bartitsu, our modern interpretations of the art should draw very substantially from early 20th century technical sources, especially those that are within the Bartitsu training lineage. This includes the jujitsu and stick fighting sequences presented in E.W. Barton-Wright’s articles between 1899 and 1901, which provide a common technical and tactical “language” for modern Bartitsu practitioners.

Thus, there is an element of deliberate anachronism inherent to the modern practice of Bartitsu. Practitioners walk a fine line between pragmatism and historical recreation. This is partly an effort to avoid simply “reinventing” or re-labelling Jeet Kune Do, Mixed Martial Arts, Reality-based Self Defence, savate defence, etc. While Bartitsu has much in common with these and similar systems, it has its own flavour and clubs are encouraged to preserve that flavour in their training.

An Example of How a Modern Style Can be Used to Interpret a “Forgotten” Style

Modern boxing is a reasonably good analogue of the amateur “scientific” style of fisticuffs that was probably practiced at Barton-Wright’s Bartitsu Club circa 1900. Because the fisticuffs of the Edwardian period was more directly influenced by 19th century bare-knuckle pugilism, there are some technical distinctions (notably a more erect stance, the practice of “milling” or revolving the hands in vertical circles, etc.) but fisticuffs and modern boxing still share many similarities of style, training and technique.

Thus, someone with sufficient experience in modern boxing is in a good position to be able interpret the fisticuffs style, by studying old boxing training manuals and applying their lessons to modern Bartitsu training. They would adjust their fighting stances, experiment with milling their fists and so-on. The same process of adjustment and interpretation also applies to the jiujitsu and stick fighting aspects of the curriculum.

What Constitutes “Sufficient Experience”?

Unfortunately, that’s a “how long is a piece of string?” question. In terms of applicability to the Bartitsu revival project, a number of months in one style might be worth several years in another. So much also depends on individual aptitudes, physical confidence/co-ordination/fitness and other factors that it’s very hard to generalize about this in any useful way. As a rule of thumb, though, a club whose members had previously trained in (kick)boxing (including la boxe Francaise/savate, Muay Thai and similar styles), both standing and ground grappling (any traditional jiujitsu style, Brazilian jiujitsu, judo, shuai jiao, hapkido, aikido, etc.) and stick fighting or fencing (arnis, singlestick, sabre, etc.) would have a good head-start in Bartitsu training.

Note that the above is just a sample list; many other styles would also be good foundations, as long as the practitioners are able to make the necessary adjustments towards the Edwardian/Bartitsu “flavour”. You can experiment by working through this random selection of circa 1900 jiujitsu and walking-stick defence sequences:

No. 4.– How to Overthrow an Assailant when he Seizes you by the Waistbelt, or Attempts to Grasp the Pocket of your Coat.

(It will be seen that in this case Mr. Barton-Wright is the assailant)

To lay upon his back, in the space of a few seconds, an assailant who seizes you by the waist, five simple movements are necessary. First, you seize his right wrist with your left hand; secondly, you take a step to the side with your right foot, next you strike him a back-hander with your right hand. Fourthly, you place your right foot behind his right knee, and lastly you press on his right shoulder, with the result that he will be thrown ignominiously on his back.

Here is another way of defending yourself, and overthrowing an assailant who attempts to seize you by the pocket of the coat. We will suppose that he makes the attack with his right hand. With your left hand firmly grasp his right wrist. Then seize his throat with your right hand, forcing your thumb into his tonsil. This will cause intense pain, and he will bend his head and body backwards in order to avoid it. In this position he is standing off his balance, and you take the opportunity of placing your right foot behind his right knee, and then proceed to throw him as before.

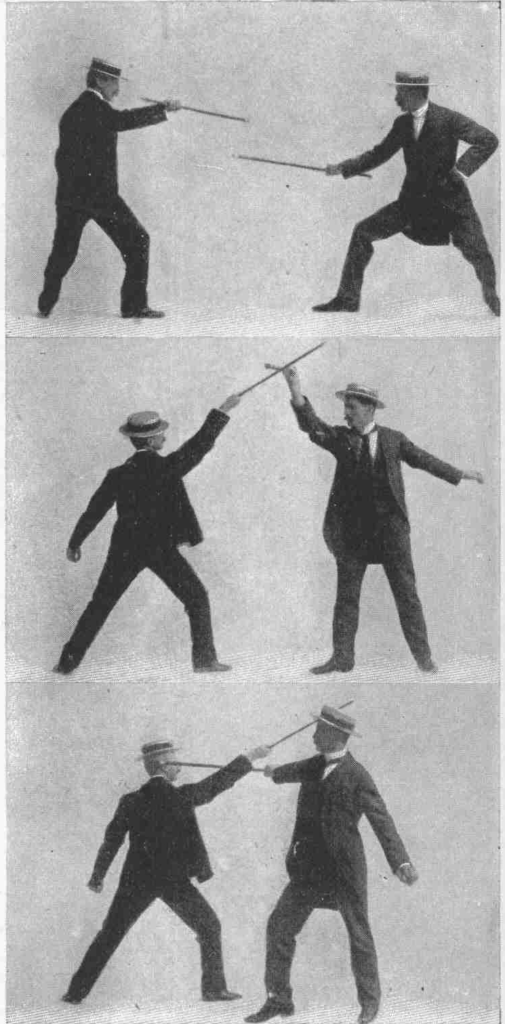

No. 10.–Example of a very Pretty Guard and Counter-blow when an Assailant Directs a Blow at your Head with a Stick.

When an assailant attempts to strike you on the head with his stick, you may receive the blow upon your stick by bringing your hand right across your face, and holding it well on the left side of your head with the back of your hand outwards, facing your opponent. Your stick should point slightly downwards to prevent your opponent’s stick sliding down yours, and striking you on the fingers.

The moment you have done this you step slightly towards your opponent’s right side with your right foot, and describe a circular right to left back-handed cut across his face, which should be sufficient to prevent him troubling you any further.

If these techniques seem at least practicable based on your past experience, you’re probably in a good place to begin the study of Bartitsu.

Learning “Forgotten” Martial Arts from Books

As martial artists, most of us are habituated to thinking in terms of learning styles from live instructors, often representing an unbroken teacher-student lineage extending back a number of generations. However, Bartitsu was left as an unfinished work-in-progress when Barton-Wright’s original Club closed in the very early 1900s. Thus, our revival requires the practical interpretation of hundred-year-old self defence texts, written in quaint Edwardian English and illustrated with photographs of strapping, moustachioed gents in straw boater hats. This process of martial interpretation based on historical material is, itself, an acquired skill; you may find it rewarding.

Certainly, this process would be a very steep learning curve for complete martial arts/combat sports novices. People in that situation are strongly advised to get a few years of suitable cross-training under their belts in the first instance. This is also part of why we advise people to collaborate with others who have complementary skills and experience, if possible.

Inside the “Combat Lab”

Ideally, a Bartitsu club is a “combat laboratory” whose members participate as martial athletes, historical scholars and research analysts. Different members of the club will bring different specialties to the project and you will be learning from (and testing) each other in your training. Some will be keen on studying the historical source material, others may be fascinated by the cross-training process. Instructors, of course, must be capable in all these areas, as well as being good teachers.

Equally important is the desire to simultaneously preserve Bartitsu as a unique cultural artifact while developing it as a viable cross-training system applied to Edwardian-era fighting styles. E.W. Barton-Wright encouraged members of the original Bartitsu Club to be open-minded; to collaborate with each other and to actively experiment with various different styles and ranges of combat. Thus, it’s vitally important for modern Bartitsu enthusiasts to study how these skills can be combined and tested against each other.

If all of this sounds like too much work, then Bartitsu training probably isn’t for you; if it sounds like an intriguing and worthwhile challenge, then welcome aboard!

Getting Started

Basically, you need at least two enthusiasts and a training venue. Clubs generally start out by attracting a small core group via word of mouth, through advertising in the local community and online. It is useful to attend or host a Bartitsu seminar if possible, to network with other enthusiasts and develop your own skills.

The following video includes highlights from a Bartitsu seminar with instructor Alex Kiermayer in Pfarrkirchen, Germany:

As you get underway, you may consider performing demonstrations to promote your club. Members of the Bartitsu Society have performed many demos at martial arts conferences and Steampunk conventions over the past several years.

Venue and Equipment

Your club’s training venue could be anything from a park or backyard during pleasant weather to a garage, home workout space, or a rented room. Some clubs rent community halls, dance or martial arts studios, or side-rooms in gyms. All you really need from a venue is guaranteed access and enough space to train safely. Falling mats are an advantage.

Your initial equipment needs will probably include:

1) copies of all three volumes of the Bartitsu Compendium for use as study guides. Volume 1 includes the complete canonical curriculum (as it was known to the editors in 2005), Volume 2 is a carefully curated compendium of resources for neo-Bartitsu styles and Volume 3 includes an extensive section on the key points that differentiate Bartitsu from similar styles.

2) training canes; classic Bartitsu canes feature solid ball handles, but a significant number of techniques require hook-handled canes. Many members of the Bartitsu Society purchase the 3/4″ rattan sparring cane from Purpleheart Armory, which is a good multi-purpose option for both regular training and sparring. Crook-handed rattan canes are available from many martial arts retailers.

Alternatively, you can make your own training canes or purchase them from other vendors.

3) boxing or MMA gloves

As you get further into your training, you’ll probably want to pick up some:

4) judo or jiujitsu gi jackets and belts or sashes (note that Bartitsu does not use a belt ranking system, so the belts/sashes are just to hold the gi jackets together)

5) body protection for contact stick fighting drills and sparring. This normally includes “3 weapon” fencing masks; martial arts/hockey/lacrosse shoulder, torso and arm protection; hockey or lacrosse padded gloves and cricket or hockey knee/shin protection. The level of armor really depends on how hard you are comfortable hitting and being hit.

6) striking targets including (but not limited to) hand-held focus mitts and a medium-weight punching bag.

7) boxing head protectors, groin cups and mouth-guards

Structuring Training Sessions

Neo-Bartitsu is an experimental cross-training process that includes a formal, set curriculum (the canonical Bartitsu sequences) as well as an open-ended repertoire of additional skills. The reconstruction of Bartitsu is considered to be an “open source” project undertaken by a community of colleagues. The object is to continue Barton-Wright’s martial arts experiments, rather than necessarily to complete them into a single, defined system. Thus, individual instructors/clubs have the opportunity to innovate and to take the material in a variety of directions.

At present, most clubs concentrate on recreation (historical interest, fitness and “academic” training) and self defence. Various competitive formats have been discussed by members of the Bartitsu Society, and it is hoped that as the hobby becomes more popular, “Bartitsu tournaments” will become practical.

Some clubs introduce each of the major skill-sets (or styles) sequentially over a period of time; for example, an intensive introduction to the basics of scientific boxing, then a detailed study of the canonical stick fighting sequences, then a period of concentration on judo or jiujitsu, before studying how to combine each style into a “Bartitsu blend”. Others practice techniques from each skill-set in every class, emphasizing the cross-training process from the outset.

In this video, instructor Chris Amendola teaches a canonical Bartitsu stick fighting entry and then a neo-Bartitsu variation at the WMAC Western martial arts gathering in Houston, Texas:

A Template for a 1.5 hour Bartitsu Training Session

* Warm-ups including exercises for strength and flexibility drawn from the 19th century physical culture repertoire. A number of members of the Bartitsu Society swing Indian clubs as a calisthenic and co-ordination exercise.

* Technique drills covering basic jiujitsu takedowns, throws and locks; boxing punches and defences; stick fighting attacks and defences.

* A representative selection of canonical self defence sequences and “twist” exercises

* Several rounds of free-sparring, which can include fisticuffs and low kicking; competitive (submission) jiujitsu; stick fighting; and/or “all-in” sparring

Resources for technical curricula can be found in both volumes of the Bartitsu Compendium. Many people begin by studying the canonical Bartitsu material presented in Volume 1 and then extending into the neo-Bartitsu practices detailed in Volume 2. The latter material includes excerpts from about fifteen early 20th century self defence and combat sport manuals, mostly produced by former members of the Bartitsu Club and by their students.

Working with Canonical Sequences

Because neo-Bartitsu can potentially include many hundreds of individual techniques from a wide range of historical systems and sources, it is not uncommon for enthusiasts to become confused or deterred at the outset of their training. Fortunately, as Barton-Wright himself pointed out:

The system has been carefully and scientifically planned; its principle may be summed up in a sound knowledge of balance and leverage as applied to human anatomy.

He also said that the Bartitsu practitioner should train:

1. To disturb the equilibrium of your assailant. 2. To surprise him before he has time to regain his balance and use his strength. 3. If necessary, to subject the joints of any parts of his body, whether neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, back, knee, ankle, etc. to strains that they are anatomically and mechanically unable to resist.

Chapters 2 and 3 of the Bartitsu Compendium, volume 2 present exercises that address certain key mechanical and strategic principles at the abstract, pre-technical level. Through their practice, it is possible to come to appreciate all the various techniques – boxing punches, jiujitsu throws and locks, stick fighting strikes, etc. – as examples of those principles in action. Thus, what might at first seem like a bewildering array of “combat moves” can be understood more holistically and more simply as “combat movement”. This is probably the ideal perspective from which to study Bartitsu.

One useful approach to Bartitsu training involves first mastering a selection of the stylised canonical sequences, a selection of which are shown in the video clip below. Note the adjustments made for safe training and clear demonstration purposes:

The next task is to “twist” the canonical sequences by having the partner acting as the “attacker” change the routine by deflecting the scripted counter-attack, disarming the “defender”, suddenly throwing a sucker punch, etc. The challenge then is for the defender to react spontaneously to regain the initiative, according to Barton-Wright’s precept:

It is quite unnecessary to try and get your opponent into any particular position, as this system embraces every possible eventuality and your defence and counter-attack must be based entirely upon the actions of your opponent.

This form of largely co-operative but quasi-competitive, challenge-based pressure-testing is carried out at 1/4 speed at first, gradually increasing the speed and levels of resistance as the practitioners gain confidence and skill through experience. Protective equipment should be worn as these exercises develop into greater speeds and harder levels of contact. Via this method, even a small selection of canonical sequences can generate a wide range of training opportunities.

The video above demonstrates how the attackers spontaneously disrupt the canonical sequences by disarming, interrupting, checking or otherwise countering the defender’s scripted actions. Alternatively, the assumption for purposes of the drill may be that the defender’s counter-attack has simply missed or failed to produce the intended effect (for example, accidentally striking across the shoulder muscles rather than the skull), creating a new opportunity for the attacker and requiring further follow-up action from the defender.

Again, the attacker’s task is to present the defender with an unscripted challenge. The defender’s task is to flow with the interruption and re-establish control over the “fight”. Note that this is not, therefore, a demonstration of self defence techniques to be learned by rote, but rather of an exercise in “martial improvisation” drawing from the entire Bartitsu syllabus, as a bridge between set drills and free-sparring or fencing.

Sparring matches ensure that our Bartitsu training stays rooted in what is combatively practical, rather than evolving into “fantasy fighting”. That said, again, free-play (sparring and stick fencing) should be balanced with scenario-based self defence exercises, acknowledging that the artificial conditions of athletic competition only mimic some of the circumstances of a real fight. Barton-Wright was adamant that Bartitsu itself was primarily a method of practical self defence.

The Bartitsu Society

The Society is a completely apolitical association of Bartitsu instructors and enthusiasts. There are no membership dues, official hierarchies or fees to pay. The Society does not maintain any form of grading or ranking procedure, though instructors and clubs are welcome to establish their own grades/ranks if they desire.