- Originally published on the Bartitsu.org site on Monday, 6th August 2018

Writing in The Sketch of December 1st, 1958, journalist Marjory Whitelaw looks back to the Edwardian era, when “perfect ladies” carried concealed pistols and knew just where to point them.

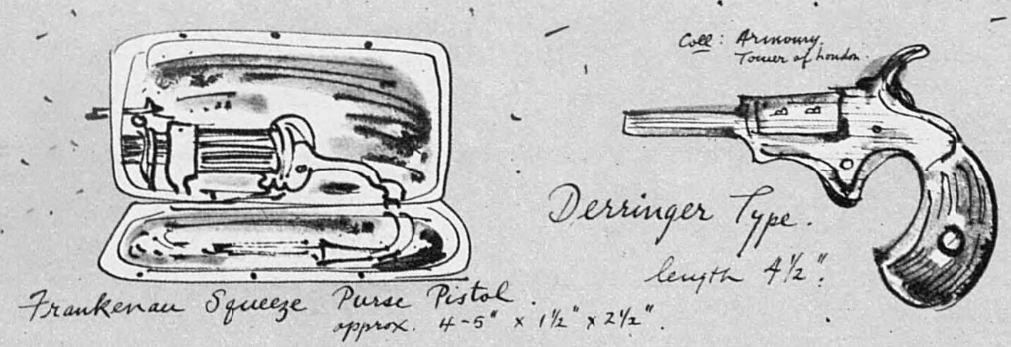

THE first I ever saw was at a dealer’s, when I was looking for something else entirely. He put it in my hand – a small purse, elegant, of fine black suede. It was slightly worn around the clasp, and it seemed, I remarked, oddly heavy for its size. The dealer beamed approvingly. “An Edwardian lady’s coin purse,” he said, “separated, as you see, into two useful compartments.”

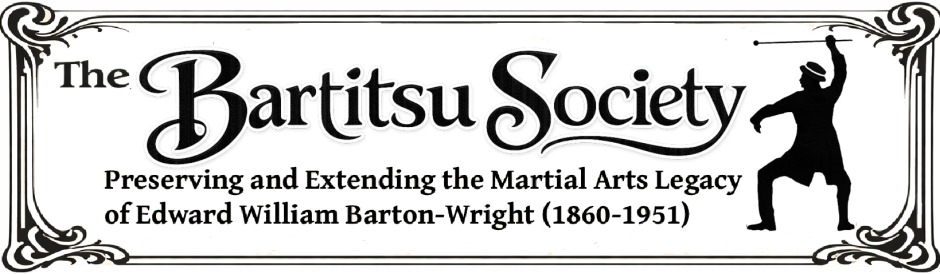

He showed me, first, the side lined with silver kid where the sovereigns and sixpences would have gone, with two of those little round safety containers for coins. Then he opened the other, l equally dainty, compartment, and there, in the place of where one would expect to find the notes, was a pretty silver pistol. Delightedly, he demonstrated how the trigger was concealed on the outside, so that it was not necessary to open the purse in order to fire.

“Vital element of surprise, you see,” he said, making his point nicely. “The perfect lady’s weapon.”

Immediately there entered my mind, as clearly as if she had been in a film, the perfect lady who might have used it; tall, beautiful, wearing black with a few ostrich plumes, an imperious, passionate Edwardian who would not budge for a man. It opened up a whole new view of life for ladies.

“Of course,” said the dealer thoughtfully, “no real lady would have required one. The occasion would never arise.” He was a gentle Edwardian himself, and he dealt in manly, antique weapons – swords, daggers and old guns. It was obvious that he could not bear the idea of perfect ladies being handy with firearms.

“No,” he said firmly, “the only person who would require this would be a lady thug.” He blushed. “Forgive me. When I say lady, I mean, of course, woman. Or, perhaps, female. Yes, a female thug.”

This satisfied him, until he looked once more at the purse.

“Of course,” he said doubtfully, “it has rather a lot of taste for a thug.”

The coin purse was a provoking mystery: it had, after all, been made for some woman, be she lady or thug. And so, I discovered, had quite a number of similar little gadgets. But for whom?

My dealer’s fellow connoisseurs of antique guns were, on the whole, inclined to support his view; their own inner lives were bent backwards in tender admiration of the lovely weapons produced between 1450 and 1850 (for it seems that guns fell into a state of sad artistic decadence in the mid-1800’s); it was difficult to get them interested in the social problems of the Edwardians.

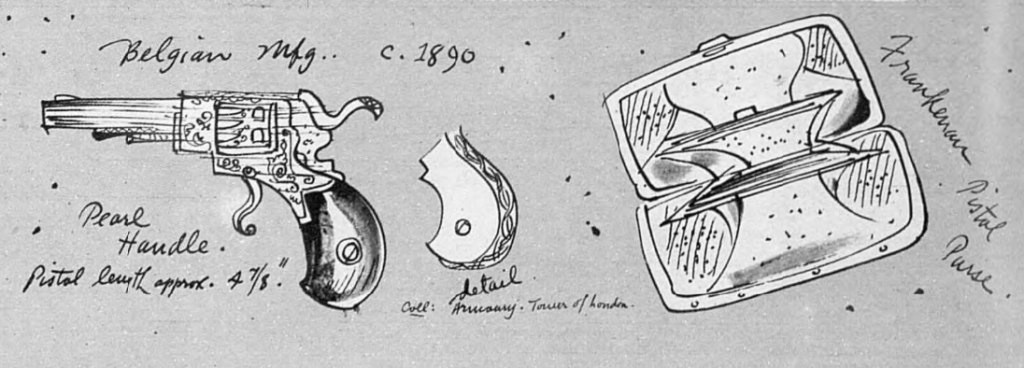

Reluctantly, they dug out their stock of the small, pretty toys: pistols in black, elegantly-chased silver, pearl with a sweet, rococo inlay in gold, a travelling model in ivory. These, they said disapprovingly, were known in the trade as “muff pistols,” for ladies forced by the demands of life to carry weapons had had a way of concealing them in large, fashionable fur muffs. How they managed in the summer perplexed me, until one old man remembered that he had once seen a charming pink parasol with a thing called a pepper-box concealed in the handle.

But it was clear that the subject pained them. Forgetting the underlying vitality of Edwardian life, they had, in their romantic minds, cherished a vision of ladies who did little except adorn life with sweet docility, doing the flowers in the morning, changing into pretty tea-gowns in the afternoon, lifting up the hearts of the gentlemen home from the day’s shooting. For these graceful, languid creatures to know any thing at all about pistols seemed to them quite out of character.

Nor would those distressing little crises, requiring ladies to think of self-protection, so common-place abroad, occur in Edwardian England; no matter how charming the lady, the English gentleman could be counted on not to lose control.

“No, it was quite unthinkable,” I was told, rather crossly, by a gentleman determined to keep his illusions.

“Confronted either with pistols or mice,” he said, “a lady would simply faint.” Alas, gentlemen, you are sitting on a shaky theory. All you have proved is that Edwardian ladies were particularly skilful at going their own way under the protective cover of a large cloud of feminine fuss and feathers.

The evidence, indeed, shows that at the turn of the century ladies who shot, and who shot well, were springing up on all sides. They were already competing at Bisley, and, equipped with sporting rifles and a convenient moral purpose, they were infiltrating on to the moors.

“They may even, by their presence,” wrote the hopeful editor of a handbook on ladies’ sports, “refine the coarse ways of men and contribute to the gradual disuse of bad language in the field.”

Nor was this trend confined to sports-lovers. The adventurous Mrs. Patrick Ness, the third white woman to get a permit to enter Kenya, took a pistol with her, and it saw her through a number of situations requiring self-protection. Elinor Glyn’s heroines, too – girls from the very best families were usually able to overcome their fear of fire-arms, without actually having to become good shots.

In His Hour, Tamara, well-bred, widowed and English, found herself one winter’s night stranded in a hut with a Russian prince who, being a foreigner, had no intention whatever of keeping control. Tamara’s immediate reaction was to grab a pistol. Unfortunately, since it was a man’s, the trigger was too stiff and heavy for her tiny hand, and she let it drop.

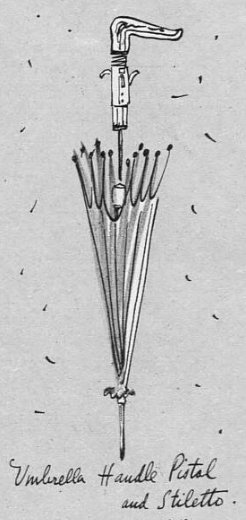

Surely it was for just this sort of occasion that the practical French had, only a few years earlier, produced the Gaulois Light, compact, in shape like a small box, it was the perfect weapon for the nervous novice, for all that was required was to point and squeeze as one would crumple a piece of paper. Ladies who, like Tamara, insisted on travelling off the beaten track could only expect trouble. But this did not deter them.

There is a heartening story of an Englishwoman who lived for a while in Chicago, at that time still a place where anything might happen. Walking in the street one day she found herself engaged in sudden battle with five or six gunmen. She held them at bay with the pistol which she carried in her bustle until the police arrived. My informant was a man; he couldn’t tell me how the bustle held the gun. My guess is that she had a cavity made under the back bow. He didn’t know, either, what type of pistol she used, but there was available at that time a pretty little round squeeze- box, rather like a powder-compact in shape, called the Chicago Protector, and I am inclined to think it was that.

Further west, of course, pistols fell readily into the category of suitable gifts for ladies. Elinor Glyn, travelling in Nevada in 1907, was visited by a delegation of miners anxious to tell her how greatly they had admired her romantic novel Three Weeks. She, in turn, visited the miners in their camp and was honoured with a presentation banquet, the gift being a small pistol mounted in pearl.

“We give you this here gun, Elinor Glyn,” the miners are reported to have said, “because we like your darned pluck. You ain’t afraid and we ain’t neither.” Elinor’s little pearl-handled beauty (she kept it to the end of her days) was probably a Colt, for this was the pistol that opened up the West. Colts’ produced the first practical revolver, and their small, beautifully-engraved and decorated products (they made Derringers also) were all the rage from 1880 up to the time of the First World War.

Many a traveller packed a Colt when setting off for the Grand Tour of Europe. My favourite is, I think, a lady who became known as the Unsinkable Mrs. Brown. Born in a shanty, she married at the age of fifteen a middle-aged miner who soon struck it rich in Colorado. When Denver hostesses (only a few years away from placer-dirt themselves) refused to accept the unlettered, naive Molly Brown, she went to Europe, with her fond husband’s twenty-million-dollar strike to back her. It wasn’t long before she spoke several languages. She dressed lavishly, she was generous, eccentric and full of zest, and she was a smashing social success in most of the capitals of Europe.

But her hour of greatest glory came on the Titanic’s maiden voyage in 1912. The sea air at night was chilly and when Molly took a few turns around the deck before sleeping, she was dressed for warmth. She wore, it is reported, extra-heavy Swiss woollen bloomers, two jersey petticoats, a cashmere dress, a sportsman’s cap tied on with a woollen scarf, woollen golf stockings and a chinchilla opera cloak, and she carried a Russian sable muff, from which she had forgotten to remove her Colt’s automatic. She was, in fact, about to send a steward below with the pistol when the crash came.

A short hour or so later she had put herself in command of a boatload of frightened passengers. She had taken off as much of her warm clothing as was practicable and shared it out among the shivering older women and the children, and, stripped to her corsets and Swiss wool unmentionables, her pistol tied to her waist, she was pulling at one oar and directing the men at the others.

“Work those oars,” she roared at them, “or I’ll blow your guts out!” They rowed, unsinkable.

Molly Brown was a woman who had the knack of adventure, a robust, Edwardian quality that she shared in her own way with those spirited ladies who made their mark as adventuresses, rather than by being merely adventurous. Respectably married, of course, not in their first youth, still beautiful and always exquisitely dressed, they found life most rewarding in Paris and at Monte Carlo. Men spoke of them admiringly as “high-steppers,” wives, coldly, as “fast,” and wherever they were, things began to happen.

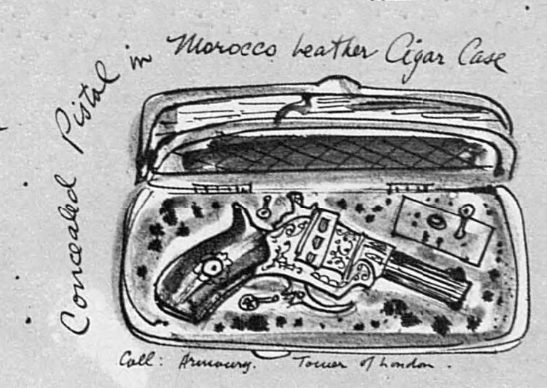

For one of them, perhaps a gift from an admiring victim, was the charming little gold pistol which, when the trigger was pulled, ejected a posy of gold flowers and a spray of scent. For them, perhaps, too, the more subtle weapons of self-protection; the little riding- whips with the damascened silver handles, slender but strong enough to contain a small revolver. Or (for one of the marks of an adventuress was the reckless way in which she smoked in public) those sweet two-sectional cigar-cases, velvet-lined, holding four small cigars and a gun.

Were these weapons often used, in those old gay days at Monte Carlo? Perhaps the surprise of realising that the lady could mean business was enough. For Englishwomen tend to the use of slow poison, rather than shooting to kill. Crimes of passion, as we all know, are found more in France. There was the case of the devoted and loyal Madame Cailloux, whose husband had been ruinously defamed by the editor of one of the Paris papers. Madame Cailloux went down to the newspaper office; and, pulling a pearl-handled revolver from her purse, she shot that editor dead. An English wife in this situation would have, in extremity, got up a petition to the House of Commons.

As for the situation today, I cannot do better than report my conversation with a London gunsmith.

“Ladies’ pocket pistols,” he said, musing. “Of course, ladies in Britain don’t require them much now. They do in Paris, though,” he went on. “Most countries abroad, in fact.”

I said, “Really, no lady I have ever known in Paris has required a pistol.” He looked at me, slightly exasperated at my doubt.

“Madam,” he said patiently, “all I can tell you is that every gunsmith in Paris is making them, and if you want a good cheap model I advise you to get it there.”

Ah, the delicious dangers of life abroad. They’re with us still.